Tristan und Isolde by Richard Wagner, 1 August 2016, Bayreuth

The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche was fascinated by Tristan und Isolde and he wrote that for stress release he preferred Wagner’s opera to hashish. This drama in three acts certainly has its fair share of intoxicating moments, but then it is also one of the greatest love stories ever told.

The musical score, when it was premiered in 1865, broke new ground in many different ways and had a profound effect on Debussy, Strauss, Schönberg, Berg and Webern. The scale of the work is immense and the task for the leading sing ers is daunting, but when it all comes together and truly gels, like it does at times in this Bayreuth production, this surely is the most romantic opera of them all?!

Nietzsche also wrote that “ the world is poorer for those who have never been sick enough for this voluptuousness of hell.” Yes, ‘T & I’ is hell indeed, if love is hell.

But it was another philosopher who had a major influence on Wagner during the ten years that it took to germinate this masterpiece. Arthur Schopenhauer’s tome The World as Will and Representation (1818) had a lasting effect on the composer. Wagner rendered Schopenhauer’s thoughts on desire, sex and our (unconscious) death wish throughout his adaptation of Tristan and Isolde. Wagner seems to conclude that ‘Love is the real cause of all human misery’, but at the same time the desire for sex is a driving force and according to Schopenhauer: ” the true essence and core of all things, the aim and purpose of all things.”

The message of Tristan and Isolde is basically: those who succumb to love will be destroyed. Love is also passion, which goes against established order. In this drama it threatens to destabilise the Kingdom of Cornwall and humiliate the Irish in the process.

Wagner knew a fair bit about unfulfilled love. He was forced to renounce his love for Mathilde Wesendock, who was married to the silk merchant Otto. The Wesendoncks provided Richard and his first wife Minna with a cottage on their property. Otto, who greatly admired Wagner’s music, was in the 1850s the composer’s most crucial patron. When Minna found out about the romantic affair (which was probably never consummated) between Richard and Mathilde it led to a marital split and the friendship with the Wesendoncks was consequently broken off.

This was my first pilgrimage to Bayreuth and I have to admit that I had butterflies in my stomach. Those dreaded seats in the Festspielhaus turned out to be quite OK and there was enough legroom for my reasonably long legs. What I was not prepared for was how different the orchestra sounds in this space. No recording can transmit that experience.

The Einleitung wafts like some intoxicating perfume from the depths of the hidden orchestra pit. The music director of the festival, Christian Thielemann is at the helm of the world’s best Wagner orchestra. But here more than anywhere else the focus is very much on the singers (because we can’t see the musicians at all).

Tristan and Isolde have a past together and we know that they fell passionately in love at first glance in Ireland. Her betrothed Morold was killed by Tristan, but not before he was badly wounded by the Irish giant. This didn’t stop Isolde from nursing Tristan back to health. As the curtain rises Tristan is acting as King Marke’s emissary and accompanying the Irish king’s daughter Isolde to Cornwall.

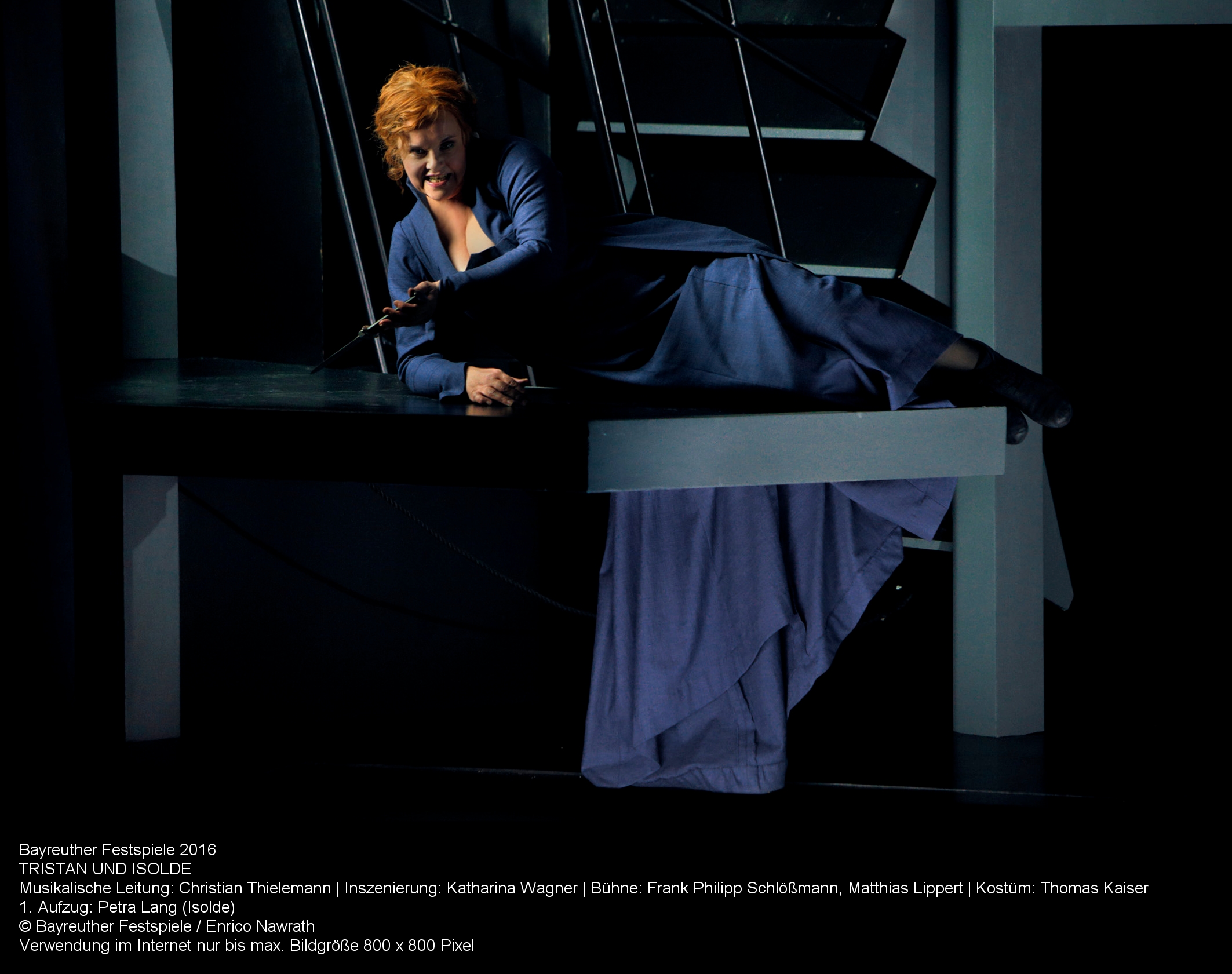

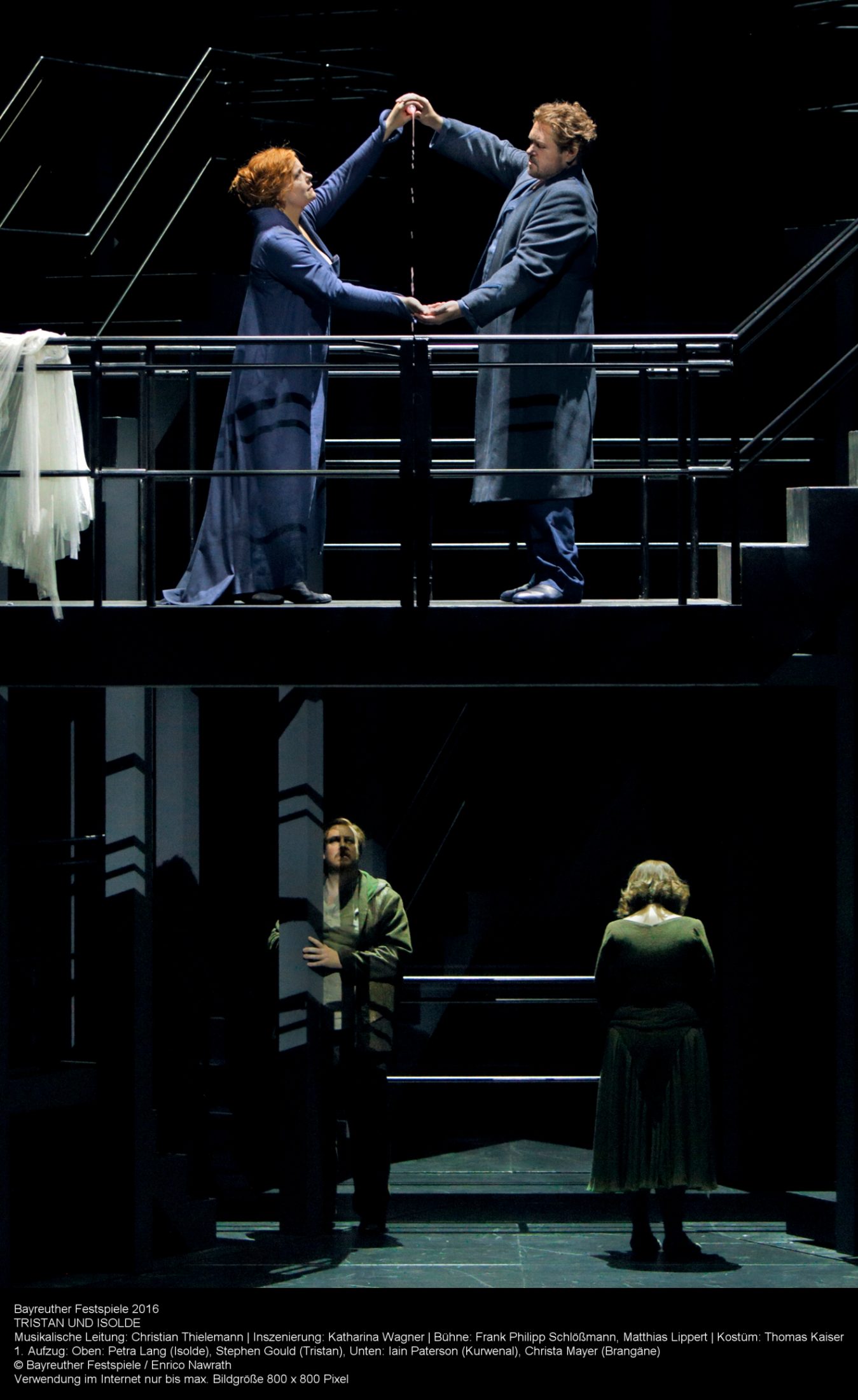

The set in Act I is a giant labyrinthine stair construction, clearly inspired by the artist M.C Escher. But instead of the faceless characters in the Dutch artists’ work, we get a very moody looking Tristan (Stephen Gould) endlessly climbing up and down those stairs in slow motion. Isolde keeps a close eye on the man who is trying to avoid her. Petra Lang as Isolde becomes absolutely furious in this scene (Weh, ach Wehe! Dies zu dulden) and it sets us off nicely on the fatal path. But when she finally gets a chance, she throws herself at the stand-offish Tristan, grabs him by the lapels, whereupon they loose themselves in a deep kiss. We’re off, let the Passion Games begin. Eat your heart out Game of Thrones fans, this is the original medieval fantasy play! By the time T & I are about to drink the ‘cup of atonement’ they don’t need any Viagra, or poison for that matter. Director Katharina Wagner may be right; this passion needs no chemical stimulus.

In Act II Richard’s great-granddaughter Katharina establishes that Isolde is incarcerated in King Marke’s castle in Cornwall from the very start. Much of this act is played out in darkness and Isolde orders Brangäne “to now extinguish the light/ extinguish its dread rays!/ let my beloved come!” Claudia Mahnke was a last minute replacement in the role as Brangäne, but you would never have known. She nearly acted her socks off. The set reminds me of some massive sleek black Bulthaup kitchen with equally enormous handles that can turn into ingenious traps. The walls are so high that the construction is more like a pit, with guards equipped with searchlights watching from above. Then Tristan is thrown into the pit by the guards as well, but there is nowhere to hide for the lovers. Isolde manages to pitch up a sort of tent with fairy lights, which gives them some privacy. Meanwhile both Kurwenal and Brangäne continue to stumble about noisily in the dark surrounding the lovers.

Petra Lang has sung many Brünnhildes and various other Wagnerian roles but this is strangely enough her first Isolde. And yes, she is not the most obvious choice for the role but that takes nothing away from her flaming, angry and intense interpretation. She is also perfectly matched by Stephen Gould who is a heldentenor at the summit of his powers. His long-breathed passages in the very taxing third act are superb and if his voice was a beer it would be Bock whereas many other heldentenors are Helles Bier with more froth than yellow substance. Lang and Gould are also compatible in size and acting range.

No need to worry about the love duet becoming dull, because suddenly the bicycle racks (well, that’s what I assume they are) very cleverly transform into bars and then cages, just to underline how impossible T & I’s sinful love is. Love is not empowering or dynamic at all, it cages you. Oh, and then there is some self-harming and bloodletting, followed by (erotic?) asphyxiation. The chromaticism signalling the lovers’ sexual expectation and excitement is perfectly illustrated in the love duet: O, sink’ hernieder, Nacht der Liebe! (Act II,scene2).

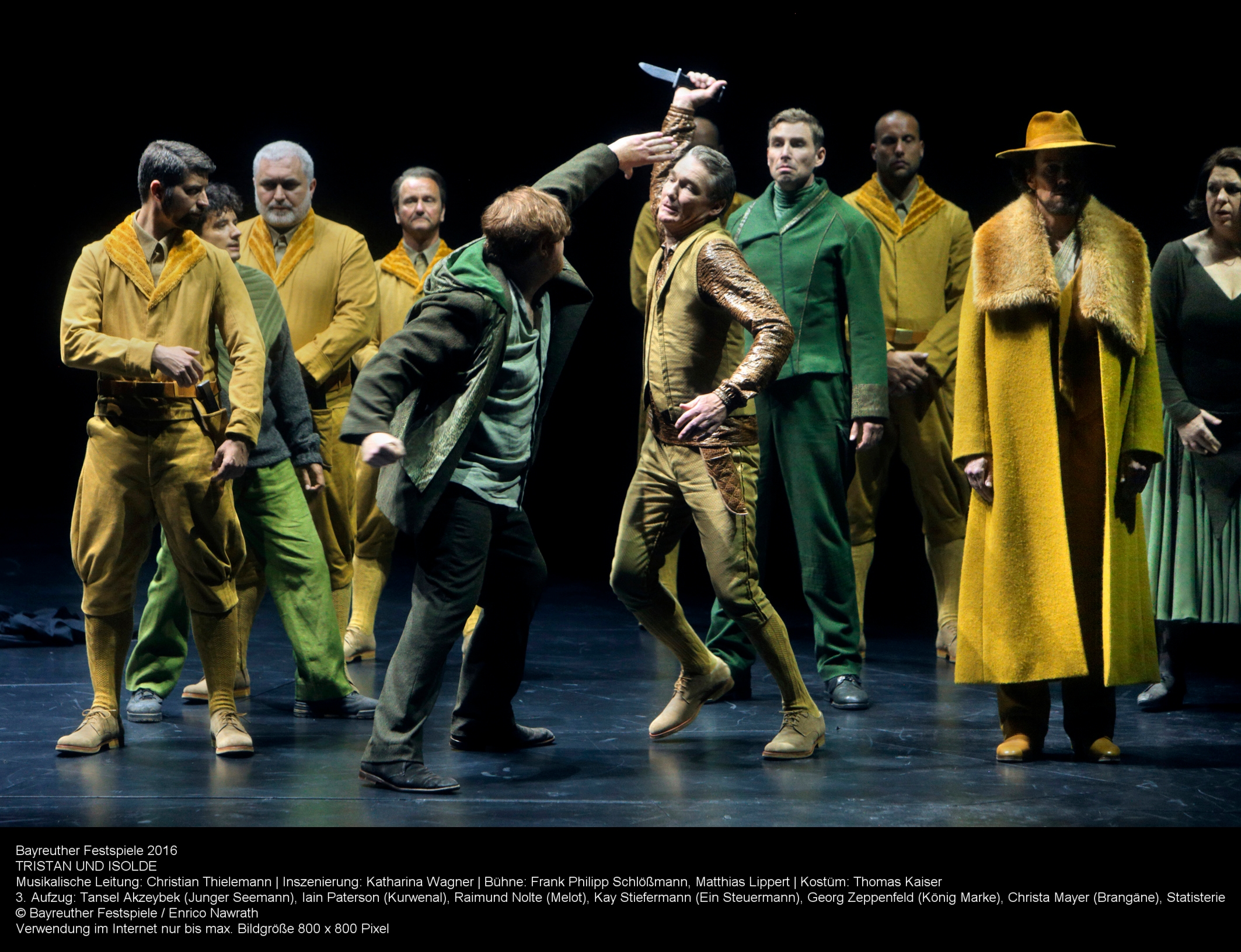

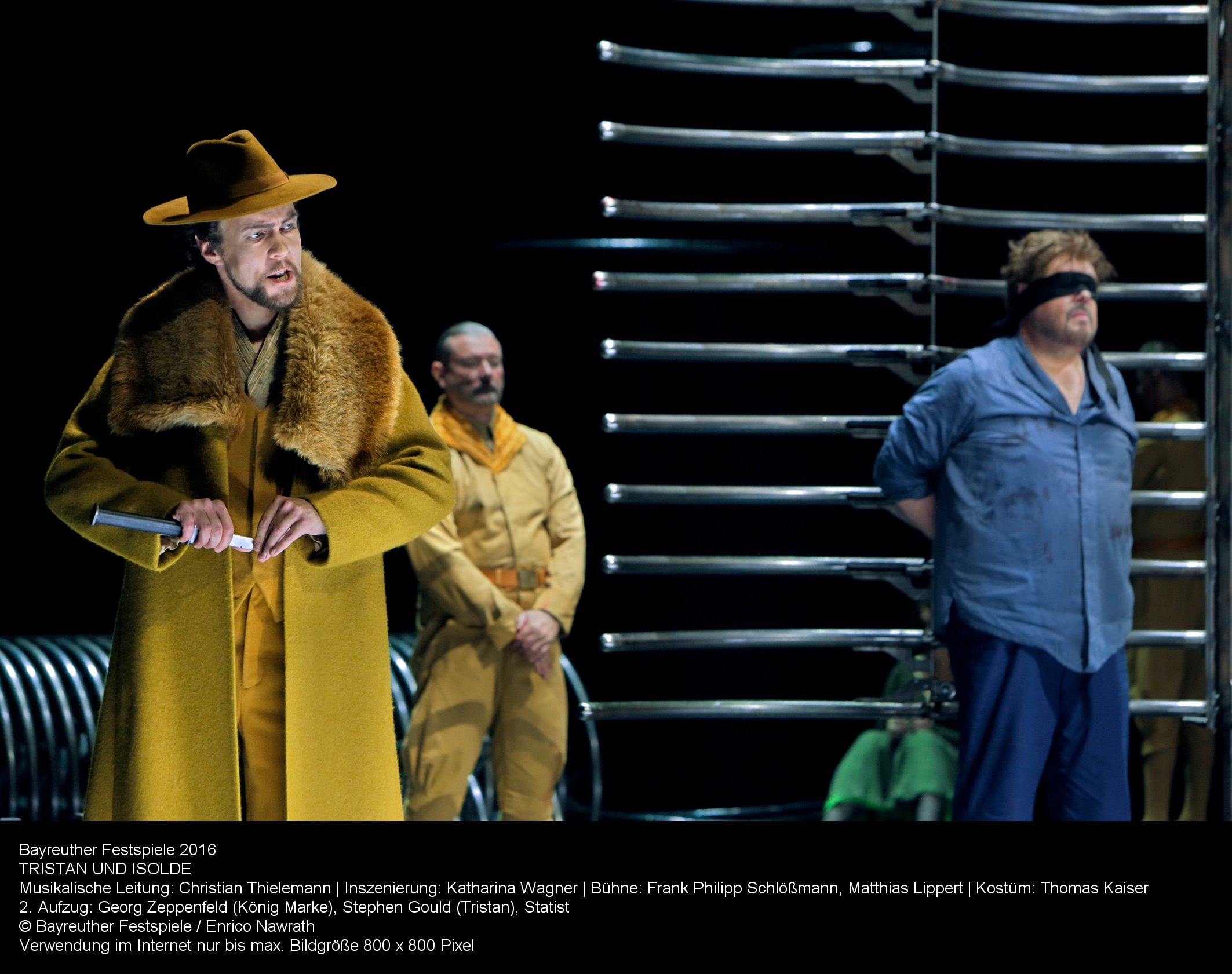

When King Marke (Georg Zeppenfeld) discovers the lovers it is is game (of Thrones) over. With his wide brimmed hat and mustard coloured outfit he does remind me of the dashing Kid Creole (and the Coconuts) back in the 80s. His men look even sillier (something straight out of a 50s science fiction movie). Oddly Georg Zeppenfeld doesn’t seem to have the physique to go with his double-espresso-without-the-froth voice, but you would think twice before standing up to this ruthless ruler. What a wonderful bass Zeppenfeld is and why haven’t I seen him before? Tristan is in this interpretation stabbed in the back by his treacherous friend Melot. No self-sacrifice for this knight.

In act III a small group of friends are keeping an eye on Tristan who lies motionless downstage left, while an English horn is heard piping mournfully. When Tristan wakes up he is feverish and hallucinates. He is in the realm of the world’s night while Isolde is in the realm of day. He rails against the light and wishes for the consummation of their love. Isolde has been sent for by Kurwenal and Tristan has visions of her, but they dissolve, collapse or are swallowed by the earth as soon as he tries to touch them. This scene has been staged very imaginatively and the otherwise empty stage underlines Tristan’s dread and loneliness. All that self-sacrifice has been in vain. Isolde has not followed him to his home in Brittany. Instead she stayed with her husband King Marke. Gould is terrific, very ably assisted by Iain Paterson as Kurwenal.

Finally Isolde’s arrival is announced, but it doesn’t alleviate the pain and Tristan’s death is played out in total darkness. He did sing earlier: “ in the bright light of day/how could Isolde be mine?” Isolde’s reserves her most intimate embrace until the end but she is not allowed to die beside her beloved. There will be no consummation of passion in death in this version and the Mustard King drags her off .

Conductor Christian Thielemann lives for this music and the Festival orchestra in the preludes perfectly foreshadows the ebb and flow, the internal and external contrasts of the drama. While accompanying the singers they never try to steal the limelight. The first act has its longueurs but otherwise the intensity in every act slowly builds up to a climax that is better than the kind of sex that Schopenhauer preferred.