It might come as a surprise to Italians and some (foreign) art experts that the Royal Collection Trust (RCT) holds one of the finest groups of Italian Renaissance drawings anywhere in the world. In total the RCT contains almost 2000 sheets of drawings from the renaissance. If that’s not impressive enough, suffice it to mention that their collection of 550 drawings by Leonardo da Vinci is the most important group in the world.

The exhibition Drawing the Italian Renaissance at the King’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace (until 9 march 2025) features more than 160 works, by some 80 different artists. What makes this exhibition extra special is the fact that more than 30 works have never been on display before. On top of that there are 12 drawings that have never been shown in the UK before.

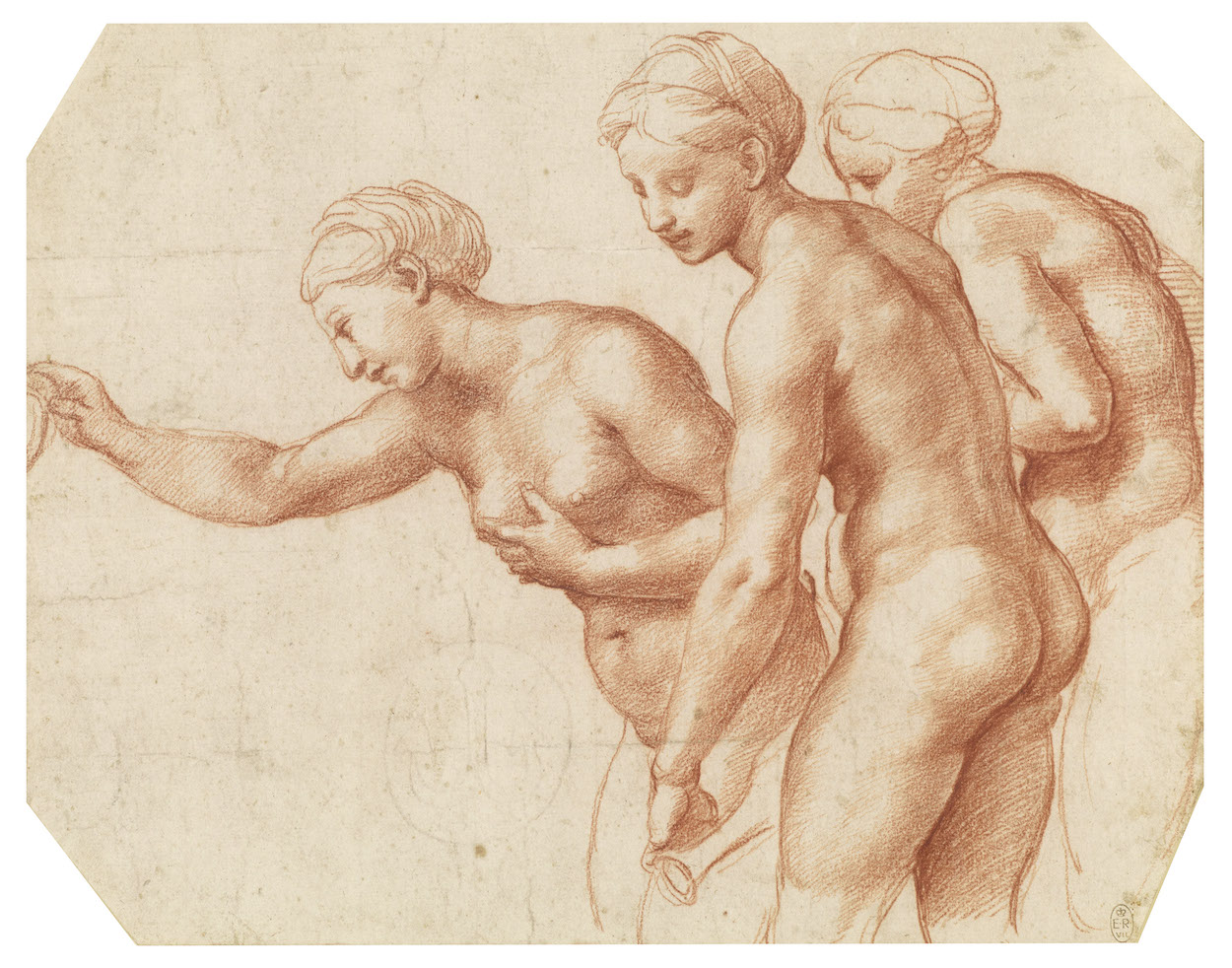

The exhibition is arranged thematically and the curators make sure that the first room, devoted to ‘Drawing the figure’ (Life drawing), immediately pulls you in. When you have Leonardo, Michelangelo and ¨The Prince of Painters¨(Raphael to you and me) drawings at your disposal, that’s not too hard. It has been suggested that Raphael’s vigorous and forcefully drawn Hercules slaying the Hydra (c.1508) was a response to Michelangelo’s technique. Raphael was impressed by his 8 year older rival’s prowess, but he admired Leonardo, who was 31 years older, even more. The softly shadowed Muse in A personification of Poetry (1509), which served as a study for a fresco in the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican, is more in keeping with Raphael’s more familiar idealised beauties. The sensual red chalk sketch of The Three Graces (c.1517), portraying the same nude woman thrice, is a popular and attractive choice. But perhaps it needs pointing out that Raphael (and his colleagues) often used boys as models for his female nudes. For theatricality there is no-one better than Michelangelo. His black chalk drawing of The Risen Christ (c.1532) shows the Redeemer, arms flailing, with the musculature of an Olympic diver and in pretty health shape for a man who’s spent three days in a sarcophagus. Leonardo’s brush drawing of The Drapery of a kneeling figure hasn’t been identified as a preparatory study for a (known) painting, but there are similarities to the angel’s drapery in his altarpiece The Virgin of the Rocks in the National Gallery, London.

In Roman times painted likenesses and portrait busts were sought after, but during the Middle Ages there was very little interest in painted verisimilitude. But portraits made a comeback during the renaissance. Raphael’s Heads of two Apostles is a so-called ‘auxiliary cartoon’, with pounced charcoal dots, that was transferred to an altarpiece executed for the church of San Francesco in Perugia (now in the Vatican Museum). Another highlight in the exhibition’s portrait section is The Head of an Old (Wo)man by an unknown (Milanese?) artist. She is portrayed wearing a white cap, looking up in devotion. This highly accomplished drawing, created with coloured chalks on blue paper, has never before been exhibited before.

Leonardo’s Bust of a Wild Man (c.1510) shows a man with a down-turned mouth and very bushy hair, wearing a crown of ivy leaves. These characteristics and the lion’s pelt hanging off his shoulders marks him out as ‘a wild man’. Experts assure us that this is not a depiction of a real person, but simply Leonardo’s spin on the much debated subject of physiognomonics.

For some reason Giovanni Bellini’s highly finished Head of an old man (c.1460-70) doesn’t feature in the portrait section, where it really belongs. Giovanni, whose brother and father were also respected painters, was in his lifetime the most important artist in Venice. When I asked the curator Martin Clayton (who also heads the prints and drawings department of the Royal Collection Trust) to pick his favourite picture, he chose the expressive Bellini drawing:

Quite a few of my favourite drawings in this exhibition are of animals Why Parmigianino’s Studies of Dogs (c.1522) has not been displayed previously is a complete mystery. Parmigianino frequently featured dogs in his works and these have a regal, sculptural quality. One could argue that Leonardo’s drawings of animals are livelier than his portraits of humans that can seem mysterious and expressionless (Mona Lisa anyone?). Just look at Leonardo’s many marvelous and energetic drawings of horses and in particular his chalk, pen and ink drawing Cats, lions and a dragon (c.1517). We see cats sleeping, prowling, playing and feeling threatened. The lions are stalking and a single coiling dragon has almost certainly been observed from life (yes, of course it has). This is a treatise on animal movement intending to show the flexibility of these beasts, the lion being the ¨the prince of this animal species because of the flexibility of its spine¨. There is no doubt that Leonardo was his era’s unequaled master of drawing human and animal anatomy. He claimed to have performed 30 human dissections and his illustrations of these investigations were only equaled (a few decades later) by the Netherlandish physician Andreas Vesalius.

The large Nash Gallery contains two different themes; religious and secular drawings. Christian subject matters were still dominating artists’ commissions, but I struggle with many of these designs for altarpieces and frescoes. I miss the vivid colours and fail to get excited. So I ask Martin Clayton to pick a work of particularly interest in this section. He points to an unusually large design for an altarpiece by Bernardino Campi (1522 – 1591).

In the secular section you’ll find designs with allegories and scenes from ancient myths that ended up on walls and ceilings. It’s a great help that the exhibition, when it’s relevant, also includes colour photographs of what the preparatory drawings look like in situ, in the final painted version. This means that we can study Annibale Carracci’s drawing of a a putto with a cornucopia and a siren, and then compare it with a photograph of the decorations on a ceiling in the Palazzo Farnese.

Even if you only have the slightest interest in Renaissance art I urge you to see this exhibition. Because there won’t be another opportunity to see so many of these renaissance drawings from the Royal Collection for years or decades to come. So, hurry on down to Buckingham Palace while you can.

You can find all the pictures mentioned in this review by searching the Royal Collection Trust site: https://www.rct.uk/search/site

Drawing the Italian Renaissance is at The King’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, 1 November 2024 – 9 March 2025