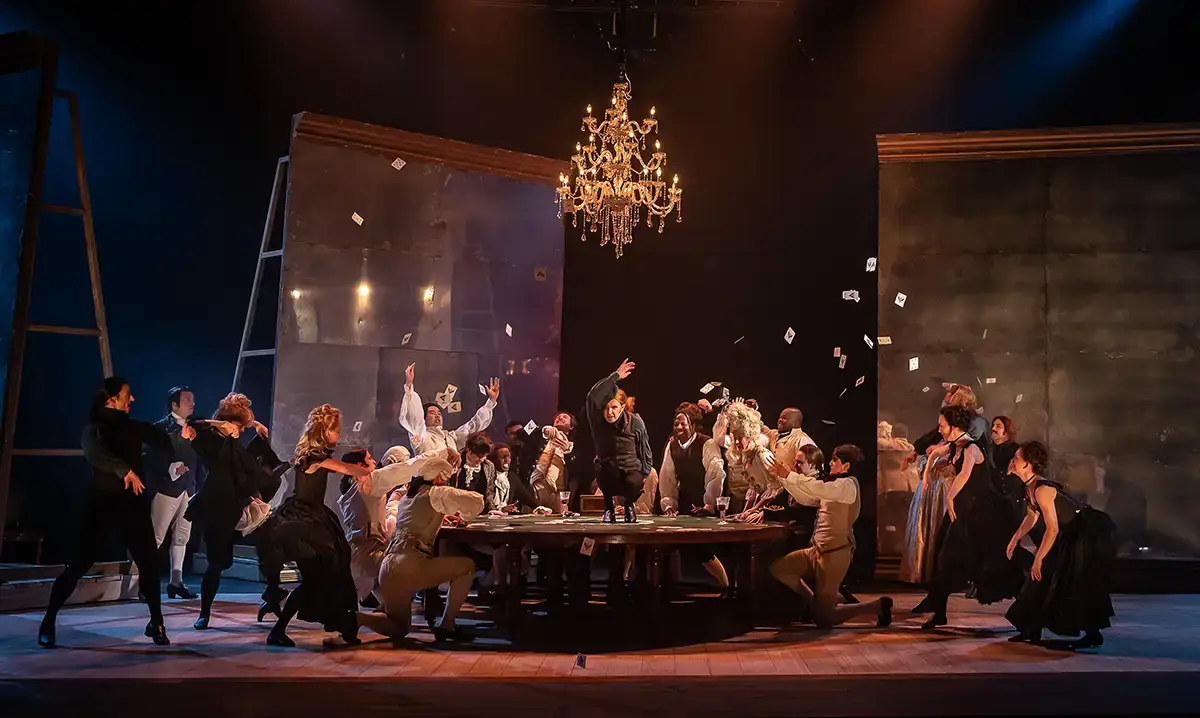

GARSINGTON’S QUEEN OF SPADES HAS ALL THE CARDS

Tchaikovsky’s The Queen of Spades – or Pique Dame – was the last opera Stalin attended. Though he had some appreciation for classical music – as adepicted in The Death of Stalin – he was never particularly fond of opera. […]