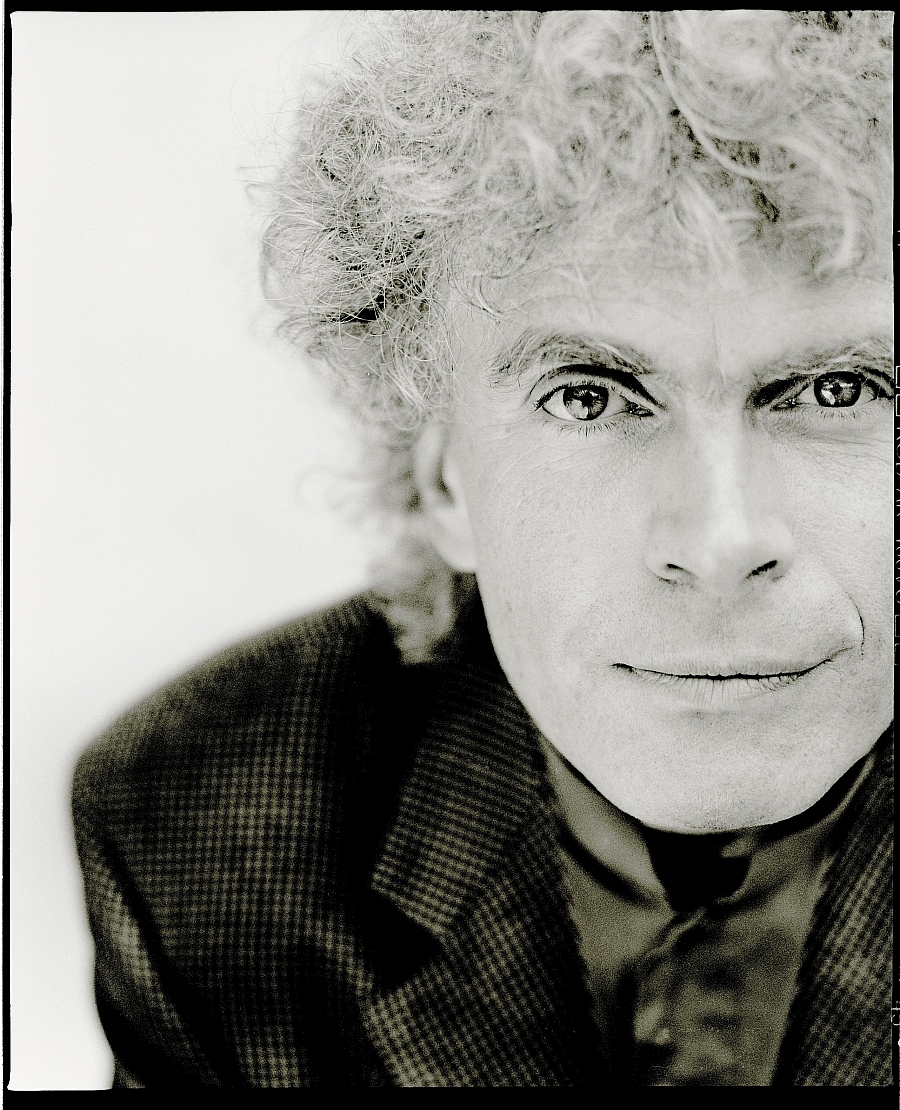

Sir Simon Rattle has had a second go at recording Sibelius’s symphony cycle. His first attempt in the 1980s with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra (CBSO) resulted in some very decent recordings that have stood the test of time. So why did he feel the need to do it all over again? Maybe I should answer that particular question straight away. Sir Simon has one of the world’s best symphony orchestras, the Berliner Philharmoniker, at his disposal and their capabilities are on paper ideally suited to interpreting Sibelius’s masterpieces. But oddly enough this superb ensemble, which was among the first orchestras outside Finland to perform Sibelius’s works, has never before recorded all seven of the Finnish master’s symphonies! In my previous blog I looked at some of the reasons why the Berlin Phil never performed the third symphony and why Sibelius fell out of favour in Germany.

In this blog Sir Simon reveals his thoughts on the inner workings of some of the Finnish master’s symphonic works.

“I think, what helps with Sibelius is when he said: Actually I am a sprite from the forest. That what he has to bring, you have to realise that it is deeply mysterious. Even when it appears straightforward in the symphonies, it often isn’t.”

No composer has managed to musically evoke the spirit and magic of Finland’s natural wonders so beautifully as Jean Sibelius. In interviews with the press and biographers he would try to deny that his symphonies (and sometimes even tone poems) had a particular programme, but privately he would give away some clues and in his diaries there are also clear indications of where he found his inspiration. Nature and the stories from the Finnish epic Kalevala were his most important sources, but there are also passages where he clearly transforms his inner feelings into music.

Simon Rattle says that here are places where you must paint pictures. “ [For instance] in the last movement of the 3rd symphony, which is so elusive, this idea that it is, as Sibelius said, ‘coming towards dawn’. This is music of sprites and spirits and not quite being able to see what is going on. The idea that the end is a hymn, not a march. Because things can fall into march time here. It is very much part of the spirit. But it is terribly important that there is a singing, pulsating [feel to it].”

Sibelius’s third and sixth symphony are less often heard in the concert halls than the other five, but on his new recording Rattle with the Berlin Philharmonic seems to have the measure of both symphonies. When Rattle and the Berlin Phil five years ago played the full symphony cycle it was the first time the orchestra performed the third symphony. It is clear that this work, the most ‘Viennese classical’ and rhythmic of all the symphonies, comes quite naturally to the Berliners.

The Berlin Phil has a splendid way with the fourth symphony as well. This is a work that can be unforgiving in the wrong hands and von Karajan was forever trying to fathom its existential depths. He recorded the work three times and his interpretations remain classics but even though Rattle’s version is equally searching and profound it has a less ponderous feel.

The symphony came about during a period of convalescence and alcohol abstinence after a life threatening tumour had been removed from Sibelius’s throat. The 4th should neither offer consolation nor a trace of sentimentality. It is noteworthy that ‘Janne’ (as his best friends called him) didn’t include a triumphant finale that had offered an element of hope in the previous symphonies. The day after he completed the work Sibelius wrote:” It requires a great deal of courage to look life in the eye.”

Rattle and the Berlin Phil demonstrate that they know how to deal with this level of anguish without turning it into the musical equivalent of the psychoanalyst’s couch.

“It makes a piece like the 4th, which is normally so desperately difficult, if not simple very, very natural”, Rattle tells me.

The four movements of the symphony contain very distinct tritones and together with the conflict that exists throughout between major and minor harmony, this creates a gripping tension. Sibelius’s dreams of composing an opera never came to fruition, but the influence of Wagner (despite his occasional denials) remained. In no other symphony is it as obvious as in the 4th.

“It is as though you had taken the whole first act of Parsifal and simply put it into a trash compactor and it came out at 35 minutes instead of four hours. Because the orchestra knows so well what is a long phrase and how you keep a long phrase through silence. “

Rattle is of the opinion that since the Berlin Phil have played Tristan and Parsifal many times, the 4th is much easier to grasp, whereas orchestras that don’t have Wagner and Bruckner ‘in their blood’ probably struggle a bit more with this work.

“Strangely the fourth symphony, which almost always has been the most difficult for me to persuade orchestras to play, was almost the easiest. The fifth which has such an extraordinary rhythmic complexity, was one of the hardest to do.”

Yes, I do get the impression that the Berliners struggle more with the 5th than for instance the CBSO did back in the 1980s when Simon Rattle wielded the baton in the Midlands. The accelerando towards the end of the second movement doesn’t have an organic feel and the transition into the third movement therefore is not wholly satisfying. Rattle seems to be well aware of the orchestra’s (very few) weaknesses, but he acknowledges that ”wherever it is to do with long phrases and with singing and with legato, like in the 4th the 6th and the 7th then the attitude (in Berlin) is : Yes, we can do!!”

Rattle makes it clear that this is not an orchestra that can be told how they should sound. They like to find out for themselves, obviously with the help of some gentle guidance by Sir Simon who knows his Sibelius.

“ What is fascinating is to find , for instance the 6th turned out here much more violent than I would necessarily have expected. Much more intense than its normal approach because it is the type of orchestra that simply, when it gets the bit between its teeth, it takes it. Of course you then must go with this.”

Rattle has deliberately not tried to mimic a ‘Scandinavian sound’, if there is such a thing.

“ The Sibelius symphonies are what I would always call a blond sound. The kind of sound that the Gothenburg Symphony plays naturally. That just simply is not natural here. “

Rattle says that technically the Berlin Phil could produce that “blond sound” but he wouldn’t want to attempt it because the Berliners have their own characteristic sound.

Simon Rattle always acknowledges how much the influence of the Finnish conductor Paavo Berglund (1929-2012 ) has meant for his own interpretations of Sibelius’s scores.

After winning the John Player conducting competition as a 19-year old Rattle was offered a position as an assistant conductor in Bournemouth. In the 70s it must have seemed like the local symphony orchestra was punching above its weight with a world class conductor like Berglund. Rattle sat in on many of the maestro’s rehearsals and was particularly impressed by Berglund’s meticulous approach to the Sibelius scores. Berglund didn’t hesitate to correct the original score if he thought he could improve weaknesses and eradicate ‘mistakes’. Rattle found out how detailed Berglund’s instructions were when the Finn visited Birmingham during the time that Rattle was in charge of the CBSO. I asked Rattle if he studied Berglund’s Sibelius scores?

“Yes, of course. And he did an extraordinary thing for me. He was in Birmingham for two or three weeks. He did a tour with the orchestra. He simply took all my scores out of the library and marked them with everything he could think of. ( gets excited and imitates Berglund ) “You know, what I do and what you should try here and think about this, this is good and if the cellos double that and that has an open string. What you should be thinking at this point and what you should be rehearsing.” So much detail. He didn’t even leave a note that he had done. Only when next I took out all the scores there were all these things from Paavo! Living with him during my time in Bournemouth I was able to talk to the orchestra. For instance at the end of the 3rd symphony it just stops. And I had this experience often with Paavo. He would be having a conversation and he’d say the last thing he had to say and then he he’d be gone. No wasting time with goodbye and see you next time. It would just stop.”

This notion that the music just stops in what seems like mid-sentence is something Rattle has used in his interpretations of Sibelius’s symphonies.

Sir Simon has visited Finland a couple of times but I was surprised to learn that he has never conducted a Finnish orchestra. That is why I asked him if he thinks it would make any difference if he were to conduct works by Sibelius with a Finnish orchestra?

“I am sure it would be absolutely extraordinary. It would be a great experience. I conducted the Royal Danish Orchestra in Nielsen’s 4th and they also did a very beautiful Sibelius 7th. The Nielsen 4th there was a kind of ownership that was astounding.”

Sir Simon is in no doubt that a Finnish orchestra would have a similar effect on the music. He feels that there is still plenty of time and there will be opportunities in the future to work with a Finnish ensemble.

Should you wish to read about Sibelius’s attempts to compose an opera I can recommend (after all I wrote it myself) the following article published in Opera Magazine: