Claude Monet ( 1840 – 1926) was a master of the variations on a theme. He was a prolific creator of colourful series of paintings containing one and the same motif. Most people have probably seen one or two works from the famous series depicting grain stacks, poplars, the cliffs at Petit Ailly, the lilly pond at Giverny, Waterloo Bridge or the Houses of Parliament.

Eight years ago I spent an afternoon, together with my family, exploring Giverny, Monet’s home, studio and magnificent garden. For a surprisingly long time Monet’s horticultural masterpiece kept my three young boys entertained. But I truly tested their, as well as my wife’s, patience when I insisted on driving into Rouen on our way to the ferry port. Rouen is where Monet made his famous series of paintings of the west façade of the Cathédrale Notre-Dame. My family had already been put through too much church crawling during our holiday in the Alsace. Obstinately they stayed in the car, despite the summer heat. Therefore my quick dash to the Portail de la Calende on the south front and the even more impressive west front of the church became much shorter than intended, so as not to expose my family to heat exhaustion.

To be honest, due to the time constrictions my bolt to the church’s frontage felt totally unsatisfactory. Returning to the car, out of breath, under my breath, I swore that I would return to find out why Monet became so obsessed with depicting the building.

I only had to wait six years.

Recently I drove down to Portugal to pick up some family-related stuff. Rouen fitted in perfectly as a stopover after a tedious ferry crossing.

Monet grew up in Le Havre, but moved to Paris where he made friends with many future impressionists. He spent four productive months in The Netherlands before settling down with his young family in Argenteuil, a village on the Seine. His wife died in 1879 and the grief-stricken painter started to devote his time to painting groups of landscapes and seascapes. The idea of creating a series of paintings on a single subject began to germinate. In 1883 he moved back to Normandy with his new partner, Alice Hoschedé, together with their combined, large family. First they rented, but eventually Monet managed to buy the property in Giverny, where he spent the rest of his life.

In 1864 Monet journeyed with the painter Frédéric Bazille from Paris to Honfleur, where a growing artist colony gathered on a regular basis. On the way the two friends decided to make a stopover in Rouen, the capital of the Duchy of Normandy, to admire the splendid cathedral and the Musée des Beaux Arts. The journey continued by boat on the Seine, which runs through Rouen. The cathedral made an indelible impression on Monet and he was just as determined as I was to return one day, in his case armed with brush and canvas, in my case with camera and notepaper.

Monet was an admirer of Joseph Mallord William Turner ‘s colourful, innovative and free spirited approach to painting. Turner was a master of depicting the same cityscape or landscape a number of times, under varying conditions. Monet was particularly impressed with Turner’s ability to capture the transient effects of light and weather. But was Monet aware of Turner’s visit to Rouen in 1832, which resulted in many drawings and gouache and watercolour designs conveying the medieval city and its cathedral? A number of the paintings were adapted and included in the volume of engravings called ‘Wanderings along the Seine’.

It may actually have been the landscape painter Eugène Boudin, who was based in Honfleur and had been young Claude’s teacher, rather than Turner, who inspired Monet’s first serious attempts to produce a series of landscapes. In 1890 Monet decided to cut down on work– related trips. Behind his home in Giverny was a field with grain stacks that he was keen to turn his attention to. An important factor was that it involved no traveling. Observing the stacks of wheat resembling giant cupcakes in all weathers just required a short stroll from his home. Fifteen of the more than twenty versions that Monet produced of the stacks were exhibited the following year in the Parisian gallery of Durand-Ruel. They were an immediate success with colleagues, as well as the critics.

The positive reactions spurred him on to continue in the same vein. In 1891 he was on the lookout for another motif and found the poplars (that were about to be cut down) along the river Epte. He paid the owner to delay the culling of the trees and made 23 paintings sitting in a boat on the river. The paint had not dried properly before two different galleries eagerly reserved most of the batch.

In 1892 Monet turned his attention to the Notre-Dame cathedral in Rouen. Camille Pissarro had, on the advice of Monet, painted a number of cityscapes of Rouen a decade earlier. But Monet had something completely different in mind. He planned a project far more challenging than painting one, or a couple of stacks of wheat in different light.

Rouen cathedral west façade is exceptionally wide, more than 60 metres. Monet had no intention to include both its towers in his paintings. But he struggled with the angle. In the winter of 1892 he set up his easel in an empty apartment facing straight on to the west front. But he was pretty quickly dissatisfied with the result and went back to Giverny to mull over a different take on the subject.

He returned in February 1893 more determined, but the apartment was no longer available. Fortunately a proprietor of a ‘lingerie and fashion store’ on the corner of the cathedral square made his shop window available for the painter to work in. When the female clients started to complain about the bearded man in the window with his brushes and easels (and his big backside), a screen was placed between the painter and the shop floor. The shop window viewpoint places the cathedral at a slight angle, similar to Turner’s watercolour and gouache painting, but for the Butter Tower, which Monet leaves out.

Over the course of two years Monet worked from three different sites. He made his observations at different times of the day, but his preference was when the light fell across the façade from right to left. This usually took place during a couple of hours in the middle of the day.

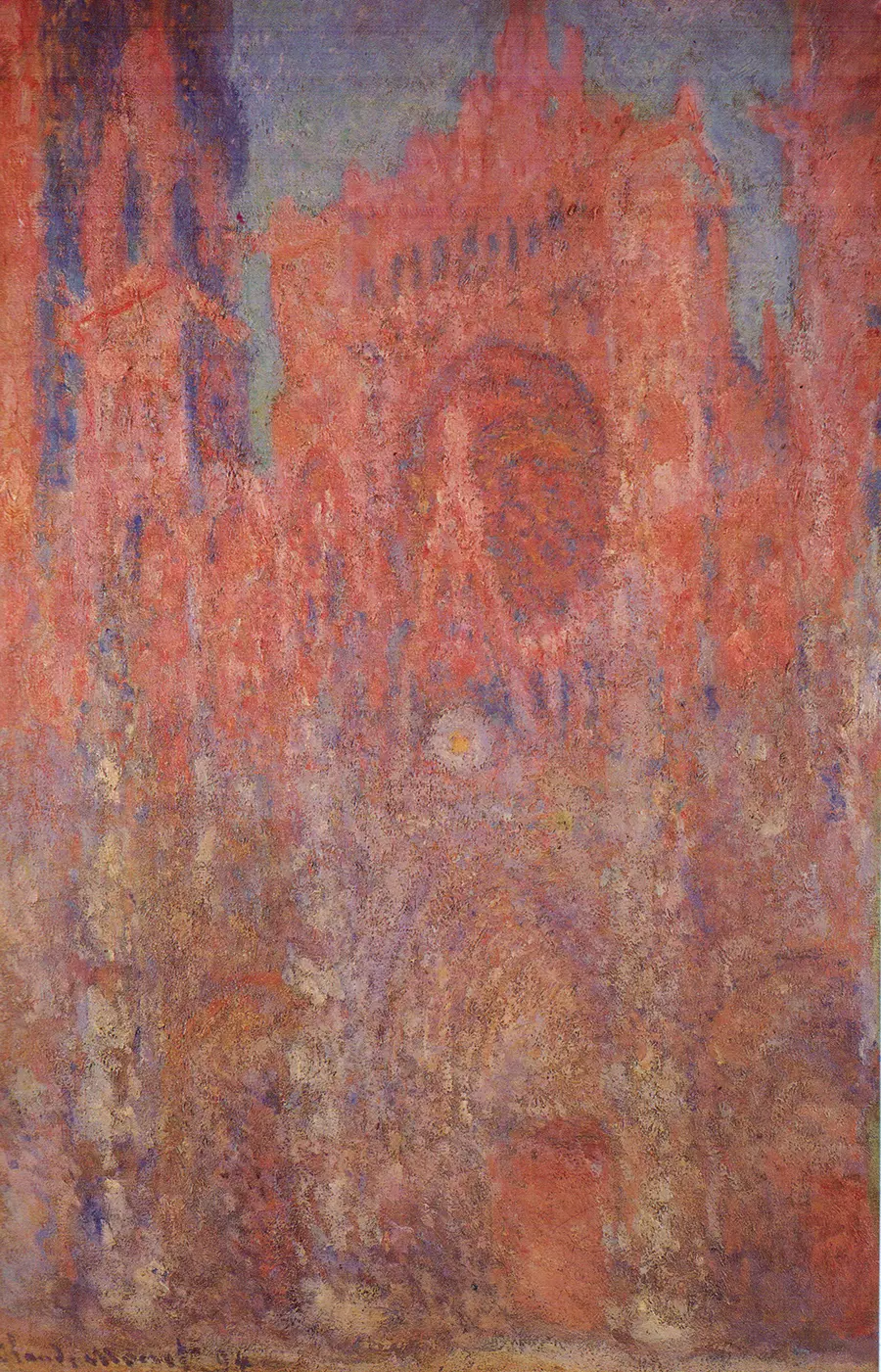

In the painting titled Dull Weather he faces straight on to the west portal, but in most of the other works his viewpoint is directed to the left side of the church. The 14th century Saint Roman Tower is included in the picture, but the 16th century Butter Tower doesn’t feature at all. In a couple of the cathedral series he leaves very little room for the sky. He takes no interest in recording the details of the intricate and flamboyant tracery, which took its cue from the Gothic English decorative style. He emphasises the encrusted appearance of the stone surface, blurs the outlines of the carved figures, the gargoyles and gothic ornaments that make the cathedral’s frontage so busy and engaging to tourists. Monet wraps the building in an atmospheric haze come rain or shine, making decorative details irrelevant. But he struggled with the ever changing play of light on the façade. To resolve these ephemeral issues, he would often work on two canvasses simultaneously and switch from one to the other to catch the variable climatic effects.

In the version called Effet du Matin , Harmonie Blanche the St Roman Tower appears to be covered in a thick layer of frost. In Façade 1 the Blood of Christ seems to be seeping out of the façade, while in Grey Weather the frontage is covered by a drab, polluted veil. One morning Monet observes the sun and shadows projecting an electrifying, vibrant blue hue across the portals and sculpture galleries. At other times the architecture seems to dissolve into thick air or melt in the bright sunlight.

The series was started in the winter of 1892 and when he finished in April 1893 he felt too exhausted and unable to even look at the work for quite a while. The working-up stage took place much later in his studio in Giverny and the whole series was finally dated 1894.

Monet writes in letters that he destroyed some paintings and was at one point overwhelmed by fatigue: ¨I am worn out, I give up, and what’s more, something that never happens to me, I couldn’t sleep for nightmares: the cathedral was coming down on top of me, it was blue or pink or yellow¨.

Make of this variation on a theme what you like, with his Série des Cathédrales de Rouen Monet once more raised the bar. Turner had already shown the way half a century earlier in the painting Rain, Steam, and Speed – The Great Western Railway, but Monet’s series was another harbinger of abstract (painting) things to come.

I land in Le Havre, Monet’s hometown, on a dark, rain-soaked night. The drive to Rouen should take a little over an hour, but a wrong turn on the ‘autoroute’ puts a spanner in my timing. The lady in charge of the small hotel on Rouen’s Place de la Cathédrale has positioned herself outside the entrance, impatiently awaiting my arrival. She is ready to go home and I get the impression that I’m her only guest. I’ve booked an attic room which gives me a fine view of the cathedral’s south side with its Butter Tower. I also have a side view of the west frontage. I can see the lantern tower and the spire very clearly. The spire, finished in 1882, caught fire in July last year and is still under wraps.The square is empty, the footfall is low,due to the incessant rain and the fact that tonight the Parisian club PSG is playing an important Champions League game.

Next morning I have the cathedral to myself, at least from my window. It’s not the most spectacular angle and Monet didn’t paint this view, but it’ll do. A flock of pigeons joins me, landing in the guttering, expecting to be fed. After breakfast (no other guest to be seen) I do get a good look at the west front. I read that the arch over the central portal depicting Christ’s family tree, was constructed and sculpted in the 14th century. But I have to remind readers that all the sculptures originally would have been painted in multi-colours and some traces of bright paint have been found. Today it is possible with the help of very precise lighting technique to offer an approximation of the original effect. I’ve seen the spectacular results of such an evening spectacular on the façade of Amiens Cathedral. But had all those sculptures in Rouen been painted, Monet would probably not have bothered depicting the frontage. It is precisely because the cathedral stones over the centuries have taken on a uniforn colour offering a sort of blank canvas sor an artist. But when the natural play of light falls across the façade and it seems to come alive, chameleon-like, revealing hidden colours and shadows, you understand why this incredible building continues to fascinate tourists and artists alike.

Rouen’s Musée des Beaux-Arts holds one of the cathedral series in its collection , Rouen Cathedral, Facade and the Tour d’Albane. Grey e des BeauxWeather, (1894). It’s my featured image at the top of the page. read y next blog review in which I visit Rouen’s surprisingly fascinating, but virtually unknown art museum.