PROM 31, 11 August, London, Anne-Sophie Mutter, Daniel Barenboim, West-Eastern Divan Orchestra

The West-Eastern Divan orchestra was formed a quarter of century ago, when a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was still on the cards. The friendship between the Argentinian-Israeli pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim and the (late) Palestinian-American literary scholar Edward Said led to the foundation of an orchestra consisting of young Arab, Palestinian and Israeli musicians that through music-making could start a dialogue and explore common ground. The orchestra’s noble philosophy ¨to seek to model a life of mutual recognition between equals through, and in our music¨, hasn’t resolved much politically. But some cultural progress has undeniably been achieved. If nothing else, the symbolical significance of an orchestra consisting of occupiers and occupied is great.

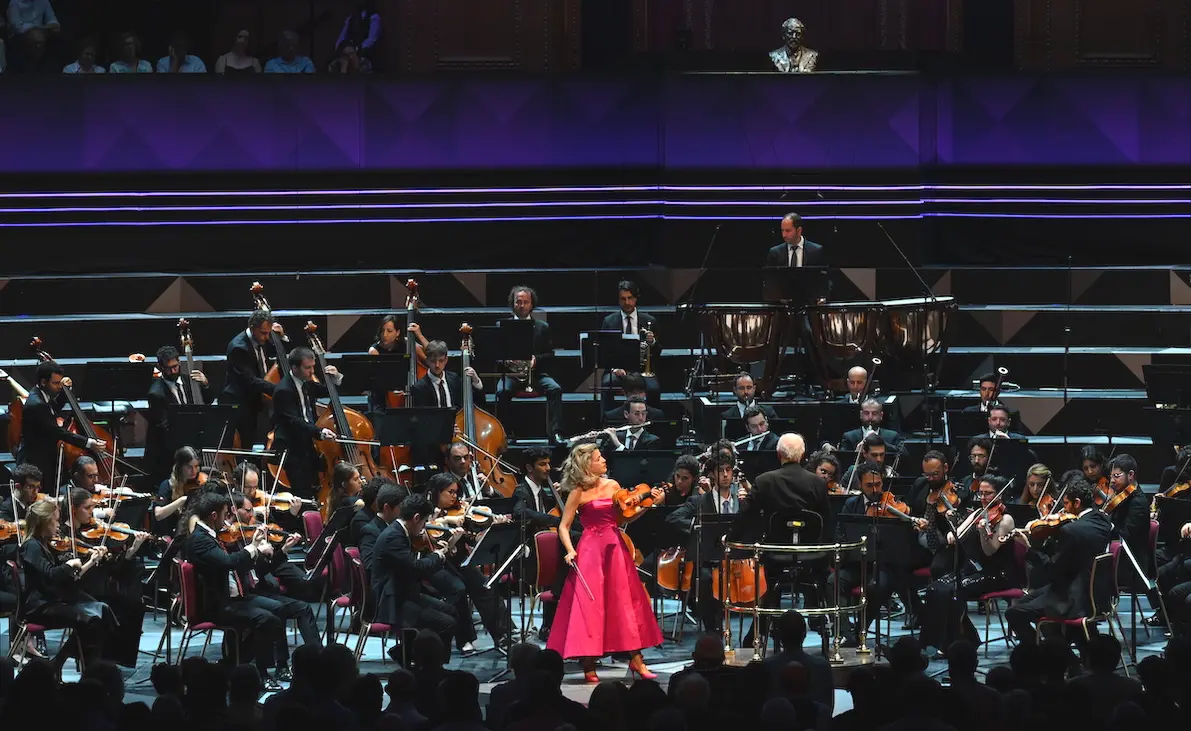

The 81-year old Daniel Barenboim came on stage looking frail, supported by Anne-Sophie Mutter, who couldn’t have been a more radiant contrast, dressed as she was in a strapless, silky pink dress. The two have known each other for at least 40 years and Mutter has once more joined the orchestra on tour. Barenboim suffers from a rheumatic condition that forced him last year to announce that he was retiring from performing. But who can turn down an invitation to perform at the Proms? Barenboim received a hero’s welcome return at the jam-packed Albert Hall. He needed some help to get settled on the rostrum, with Mutter looking a bit concerned. But once seated Barenboim, despite hardly being able to lift his baton above breast height, was in total control. Like many of the best conductors, Barenboim’s eyes, his aura (and his slightly intimidating rehearsal manner) steer the orchestra in the right direction. It probably helps that his son, Michael Barenboim, is the orchestra’s leader (as a violinist).

How many hundreds of times has Anne-Sophie Mutter played the Brahms Violin Concerto? In these classic works she remains a consummate professional and at the top of her game. In this Concerto the soloists is made to wait for about three minutes before making a hot-tempered entrance, as if to say: I’ve waited long enough! Mutter is ideally suited for this graceful,very technical and romantic material. Her style is incredibly clean, burnished and yet expressive. She packs a punch in the opening cadenza. Joseph Joachim should have had a credit for his contributions to the concerto and to honour him, Mutter plays his cadenzas. Mutter is known for her attention to detail and her vibrato (which is perfectly acceptable here). She knows how to spin out the tranquillo section, only a barely withheld teardrop away from sentimentality. She is in a (master)class of her own in this genre. And we haven’t even arrived at the superbly elongated Adagio. The oboe languidly introduces a four-bar phrase , which becomes a six-bar phrase, only to expand to eight. The violin responds by embellishing the phrase and Anne-Sophie Mutter adds some lush on top. The Lord Dunn-Raven Stradivarius she is playing at this occasion surely adds some extra warmth to the movement.

In the Finale Brahms goes all Hungarian with some double-stopping thrown in for good measure. Mutter never makes it a display of her virtuosity, there’s always plenty of tonal variety and she gives it a finish bursting with energy that even makes Barenboim sit up. The well-drilled West-Eastern Divan orchestra responds throughout with alacrity and zest. Barenboim’s every now and then with is left hand contains their enthusiasm. They know what is expected by the maestro who, through his academy in Berlin, has provided some of these musicians with an opportunity to start a career.