BBC Proms, Royal Albert Hall, Friday 28 August 2015 prom 57

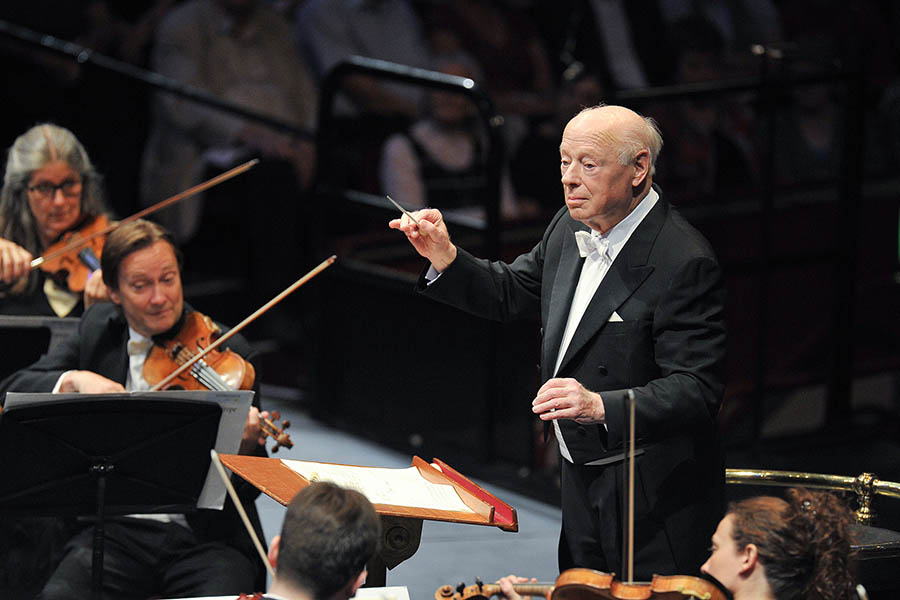

I have no idea “how many holes it takes to fill the Albert Hall” , but at the Chamber Orchestra of Europe’s recent BBC Proms concert (no.57) the hall was packed to the rafters. Not a single hole to be seen. This was the orchestra’s eleventh visit to the Proms and, yes, the Chamber Orchestra of Europe (COE) is well established in this country, but with Bernard Haitink conducting you are guaranteed a full house. That is simply a fact. The maestro can pick and choose who he wants to work with and the COE have clearly over the past few years been in his pick n’ mix bag.

I was lucky enough to attend the COE’s rehearsal at the Royal Albert Hall. The calm authority that Haitink exudes is a lesson in itself for any youngish conductor. This is still one of those professions where you have to earn your stripes and there is no known quick route to becoming a great conductor. Any impatient baton wielder should remember that most maestros only improve with age. Haitink’s eyelids are now slightly drooping but make no mistake, his ears don’t miss a trick. He rarely interrupts the flow during the rehearsal: a facial expression, an authoritative, but not unkind look at a section of the orchestra, an elegant wave of his left hand is enough to signal what is required. This orchestra with its very experienced musicians reads the signals quickly. At the end of the rehearsal Haitink thanks and praises the orchestra and says: ”Have a good concert tonight because it is a wonderful audience. And they also think they are a wonderful audience!” Laughter all around. Haitink has nailed it: Prommers are a self-righteous lot, but what a (sometimes even overly) generous audience they are.

Schubert intended the Overture in C major (D591) to sound like the opening of a Rossini opera. Haitink and the COE start rather tentatively but there is intent in this approach. A typical Rossini overture starts slowly, warming up elegantly, so that the crescendo will have a maximum impact. Schubert and the COE plagiarise perfectly and if I had been told this is a work by Gioachino, I would have believed it.

Maria João Pires enjoys a felicitous collaboration with the COE and I don’t know of any better interpreter of the Mozart piano repertoire. There may be more adventurous keyboard virtuosi and peddlers of the ‘authentic’ style , but I like Pires’s ‘hammerless’ approach. She will always ignore pedal instructions in favour of clarity. I own the box set of her Erato recordings from the 1970’s , so I came well prepared. Her interpretation of Mozart’s piano concerto No.23 in A major (K488) doesn’t appear to have changed hugely, other than that the adagio has gained more depth. How could it not 40 years later? From where I was sitting during the concert the tiny Portuguese virtuoso seemed to disappear into the giant Steinway during the adagio only to reemerge for the virtuosic hustle and bustle of the allegro assai. The COE wafted in and out appropriately and while this might be relatively easy for them to play, for the soloist it is no mean feat to make K488 sound lyrical, brilliant and effortless.

Schubert’s Symphony no.9 in C major was originally published as no. 7 and in the latest edition of Franz’s works it is numbered as 8. Then there is the question of how many sections should you repeat. The ‘Great’ C major was once considered unplayable and the length of the symphony also put some orchestras off.

Having recently listened to Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s interpretations of the work with both the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra and the Berliner Philharmoniker, I was really looking forward to Haitink’s take on things. I was not disappointed and interested to discover how different (in mood) the interpretations are.

The COE and Haitink inject some fresh mountain air to the first movement, ma non troppo. The opening horn solo puts you in the romantic vein, but Haitink doesn’t really have time for that, after all he is Dutch. Haitink really gives the three trombones – a complete novelty in the 1820s – a prominent role and they are allowed to shine in their solos (albeit pianissimo). The Andante con moto could not have been played more delicately, without loosing the rhythmic tread that becomes more inevitable as we move up the mountain. Well, I assume we are climbing a mountain, with just a little pause to empty our (walking) boots of the stones gathered. Then the cellos mysteriously guide us up another, slightly darker, path. Key changes abound in this piece, but it is more difficult to smooth them out than to stress them and if you want a ‘modernized’, edgy Schubert, then Haitink is not your man. He opts for most of the repeats and I believe that he only in the finale may have left out a couple.

Schubert here makes his scherzo slightly more heavy going than usual and Haitink doesn’t attempt to lighten the step by stressing the dance elements. This is also where the COE live up to their name. Despite having 40+ members on stage they can still sound lithe like a chamber orchestra when required. By the time we get to the finale we are virtually paragliding up that mountain. The winds are sturdy the higher up we get, but at least they push us up. The woodwind and brass sections deserve a special mention. Throughout they keep the legato melodic line going and particularly in the last two movements they provide a mostly very subtle pulse throughout.

With this lot there is no stopping Schubert’s majestic 9th… or 7th or… 8th, or whatever ‘Great’ symphony.

P:S: If you live in the UK you can see this concert on BBC 4 at 7.30 Friday the 4th of September. after that it will be available on iPlayer.