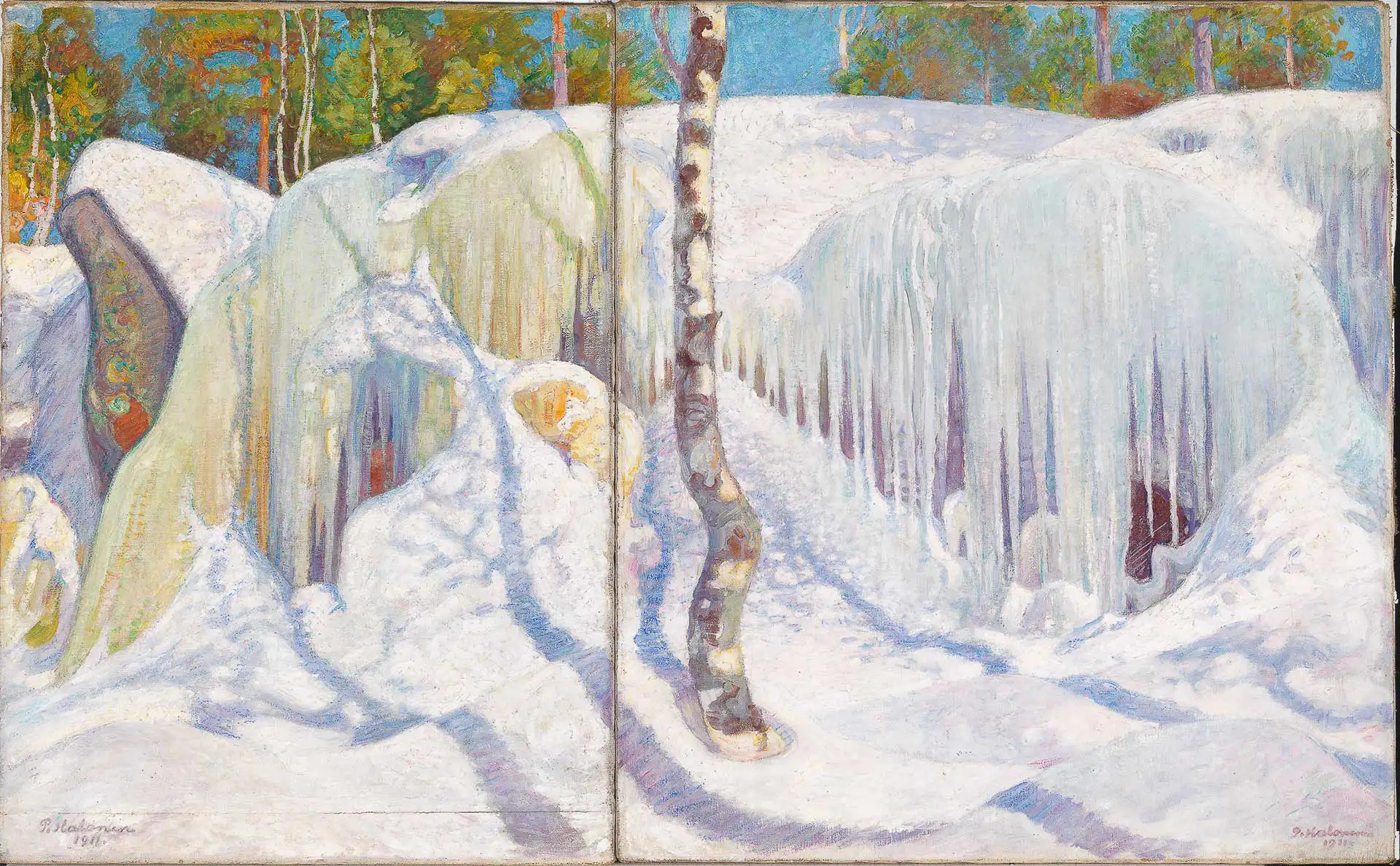

Pekka Halonen’s snow landscapes are symphonies in white, rooted firmly in the Finnish home key. He rendered the textures and tonal variations of snow with a sensitivity unrivalled by his contemporaries – arguably even surpassing Monet.

Halonen’s snowscapes fostered a profound sense of national pride at a time when the Finnish identity was under threat from aggressive Russification.

Pekka Halonen, un hymne à la Finlande, currently at the Petit Palais in Paris until February 22, 2026, features more than 130 works and marks the first major retrospective devoted to the artist outside Finland. The exhibition will in the spring travel to The Netherlands and subsequently to Denmark.

After Russia’s victory over Sweden Finland was granted autonomous status within the Empire in 1809 by Tsar Alexander I. However, the Russification, the periods of oppression and assaults on the Finnish autonomy that occurred under Nicolas II led to widespread passive resistance, strikes and draft evasion.

Pekka Halonen (1865–1933) grew up and started his career during a period when the country was striving to shape and determine its national identity. An important source of inspiration for painters, composers and writers was the Kalevala (1835), a collection of a epic myths compiled into a single volume that, over time, acquired the status of a national epic. Unlike his more famous contemporaries – Akseli Gallen-Kallela and the composer Jean Sibelius – Halonen felt no need to portray the heroic tales and the mythic origins of the Finnish people. He once said: ¨ The Kalevala has no need for our pictorial help or literary interpretation… I think its impregnating effect should instead come about through inner understanding and assimilation.¨

Pekka Halonen was born the same year as Gallen-Kallela and Sibelius. However, unlike many of his artist friends of the era, his mothertongue was Finnish, rather than Swedish. His father was a farmer and an itinerant decorative painter of churches in eastern-central Finland, and it was from him that Pekka learnt to draw and to use oil paint from an early age. He later moved to Helsinki to attend the Finnish Art Society’s Drawing school, where drawing formed the core of the curriculum, whereas oil painting was not on the syllabus. Paris attracted many Scandinavians at the time, and in 1890 he secured a scholarship to study at the Académie Julian.

In Paris he encountered the work of Jean-Francois Millet, whose images of peasants toiling in bucolic landscapes made a strong impression on him. Even more influential were Julien Bastien–Lepage’s earthy, harsh depictions of peasant existence. Returning to Finland the following summer, Halonen embraced Bastien-Lepage’s credo: ¨Nothing is good but truth. People ought to paint what they know and love…. [I want to] paint the peasants and landscapes of my home exactly as they are¨.

The influence is evident in The Reapers (1891), where Halonen depicts his brother – with his characteristic Finnish features – pausing to sharpen his scythe in a field in Northern Savonia, while others are busy making hay in the background. The painting conveys the soul and spirit of peasant life in almost heroic terms, practically anticipating the social-realism style forced on artists by the Soviet government in the 1930s. This, maybe somewhat unfair, comparison should not detract from Halonen’s remarkable achievement in creating a work that could also be read as Finland’s stubborn struggle against the uncomprising Russian regime.

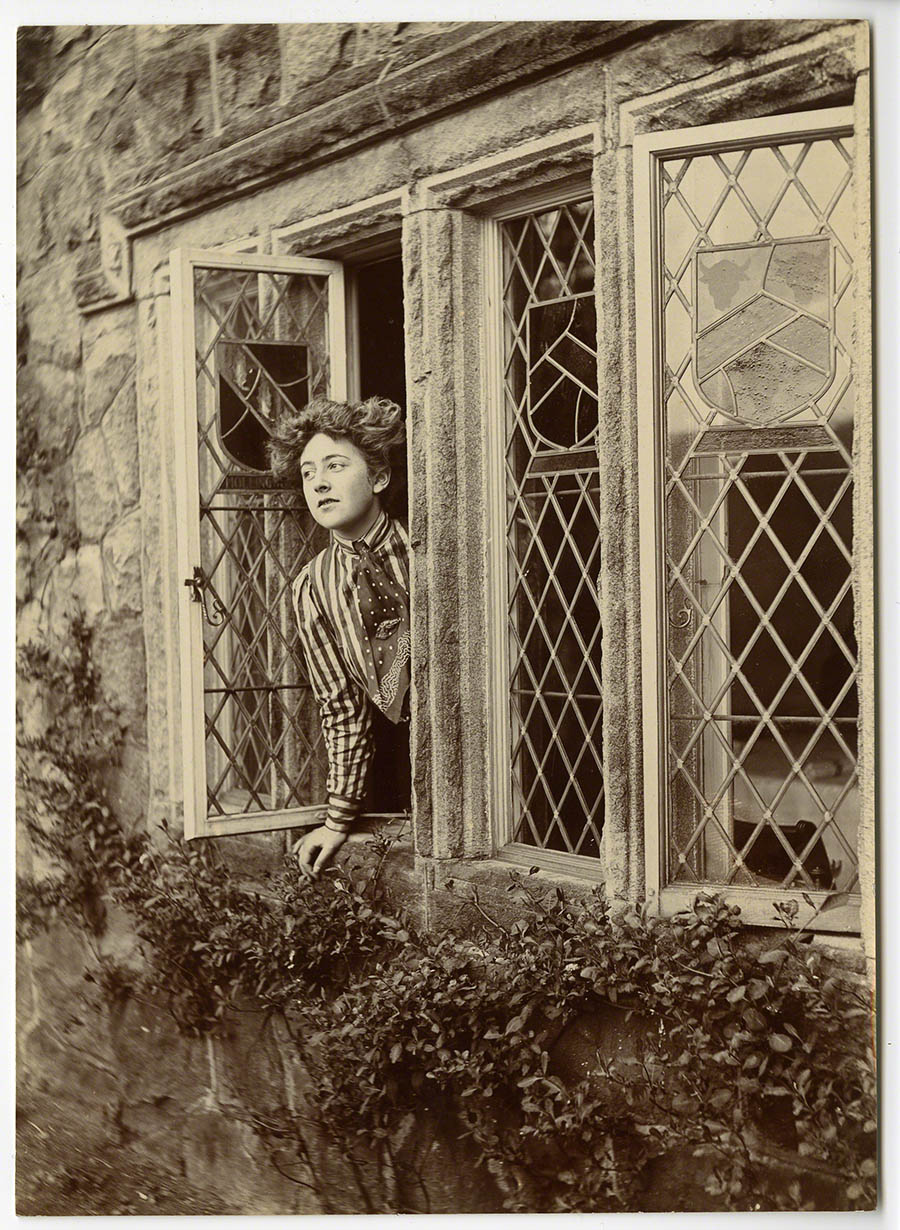

The Reapers was Halonen’s breakthrough work and it once again ensured him a scholarship, which enabled him to return to Paris. He switched to another private school, but this proved disappointing. After meeting Paul Gauguin – who had recently returned from Tahiti – Halonen became his student at l’Académie Vitti. His admiration for Gauguin is evident in a letter he wrote to his future wife Maija Mäkinen: ¨He knows everything about everything. And he is not narrow-minded like most French people.¨

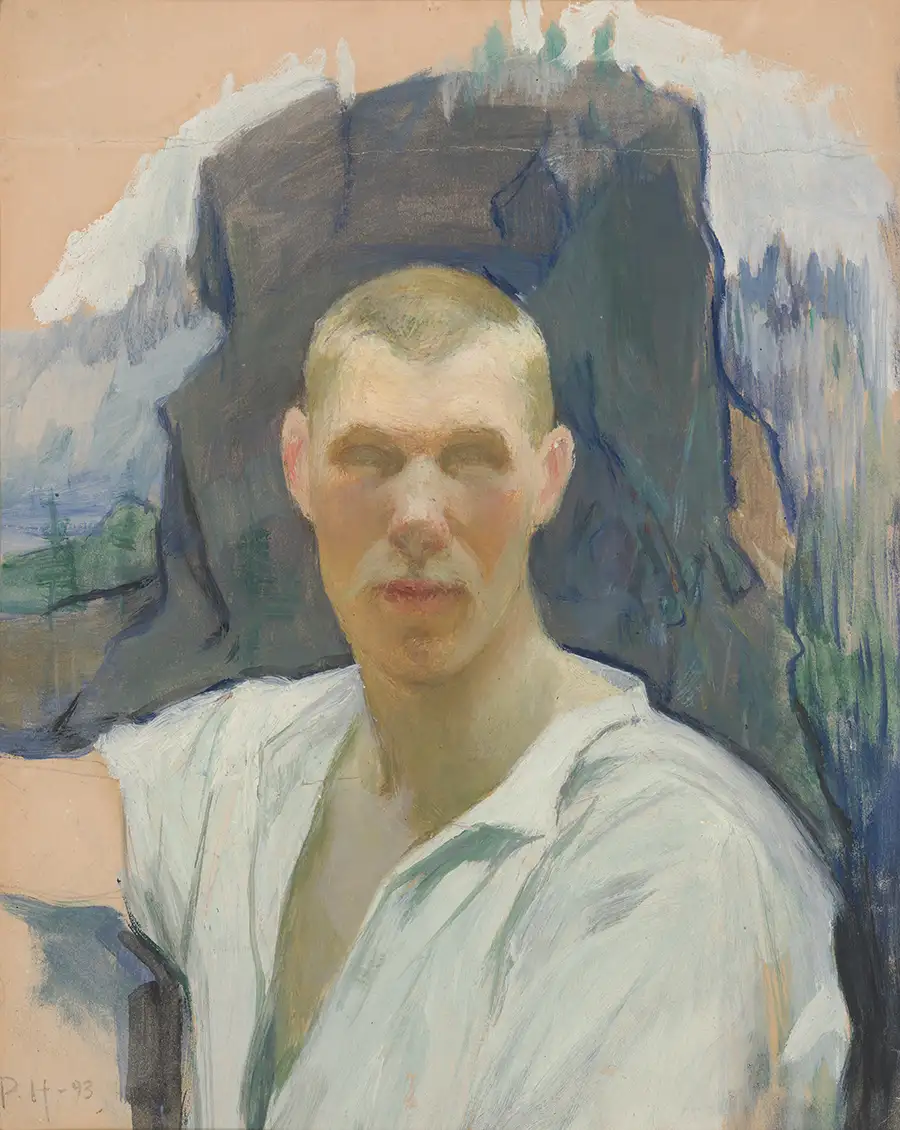

Gauguin’s influence is visible in a Self-Portrait from 1893 in which Halonen appears to be indifferent to creating a mere physical likeness. The background, dominated by a large rock formation and trees, with the sky only half finished, forms a two-dimensional picture plane typical of Gauguin’s work. Halonen’s face is illuminated and he seems to look directly at the viewer, however, on closer inspection it emerges that his eye sockets are shadowed, obscuring the whites of his eyes and his pupils. He faces us, yet he appears to be looking inwards, rather than outward.

The painting may reflect Halonen’s discovery of the Theosophical movement – which offered a conception of spiritual wisdom beyond institutionalised religion. Like many of his Finnish contemporaries Halonen found that the Kalevala’s mythical world – which represented a golden age for nationalistic Finns – aligned with Theosophy. The movement’s synthesis of philosophy, religion and science were consistent with the efforts to articulate a distinctly Finnish cultural and spiritual identity.

Pekka’s mother, Wilhelmina, was deeply religious, but she was also a composer and a proficient player of the kantele – a zither-like instrument that is played by Väinämöinen, the central character of the Kalevala. She introduced her nine children to classical music and literature. Pekka himself became sufficiently accomplished on the kantele for Sibelius to compose Lullaby for him to play at a friend’s birthday celebration.

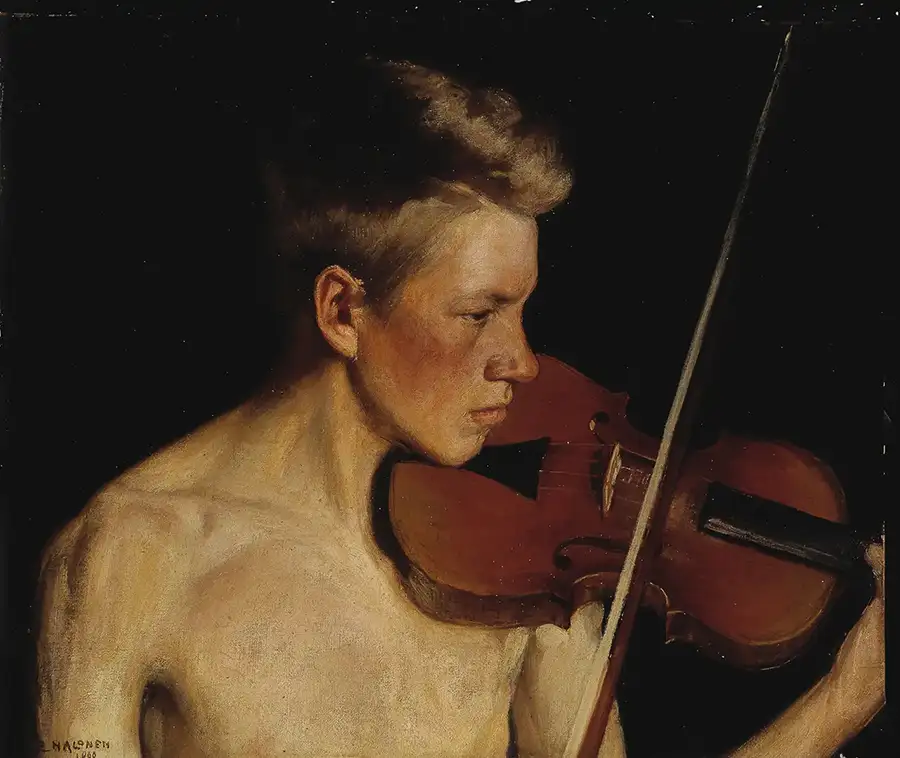

During a trip to Karelia in eastern Finland, Halonen painted Kantele Player (1892), depicting a musician plucking his instrument while appearing to be in a state of ecstasy. Pekka’s younger brother, Heikki, became a professional violinist and performed as a soloist and concertmaster with several Finnish orchestras.

Pekka portrayed him in The Violinist (1900), though the work is not a straightforward portrait. At the turn of the century Heikki was already in his thirties, yet he looks to be barely out of his teens in the picture. His upper body is naked, suggesting that the painting should be interpreted in a Symbolist spirit, as an image of Music embodied in Flesh.

The Petit Palais exhibition devotes a room to works with a musical connection with Sibelius’s Finlandia playing on a continuous loop. Two of the most well-known portraits of Sibelius, painted by Albert Edelfelt and Eero Järnefelt, ate also on display. Music was very important in the Halonen household: Pekka’s wife Maija was an excellent pianist and she often played for her husband while he worked.

Pekka and Maija already had two children when they decided to build their own home on the shore of Lake Tuusula. The transport connections from Tuusula were good – Helsinki was only a short train ride away. Inspired by traditional Karelian log-house architecture Pekka and his brother Antti began constructing the residence in 1899, which was named Halosenniemi. Sibelius became Pekka’s neighbour when he moved with his young family in to their custom built home, Ainola, in 1904. Remarkably, around the turn of the century many of the country’s most famous artists, writers and musicians were attracted to the beautiful lakeshore and settled there or visited for longer periods. For about two decades there was a close-knit, very lively artist community that got together at irregular intervals, and provided a welcome social and cultural stimulation.

Sibelius and Halonen became close friends and were the only artists who settled permanently in Tuusula (now Järvenpää) until their deaths. Two of Halonen’s landscape paintings occupied pride of place in the Sibelius family’s living room, and a number of his works are still on display at Ainola.

At Halosenniemi, the Halonen family could grow much of their own food, pick berries and mushrooms in the woods, and fish in the lake. The immediate surroundings of the house and studio provided an inexhaustible source of sustenance as well as inspiration for Pekka’s art.

Late in life he explained in an interview: ¨I have the whole Louvre and the world´s most precious art treasures right here on my doorstep. I need but step into the forest to see the most wonderful works of art ever created – and I ask for nothing else.¨

Indeed, he often had to do no more than step into his own garden to find subjects for his paintings. Halonen’s clusters of tomatoes – from unripe pale and celadon green to bright, beefy red – with stems and vines sprawling across the canvas, capture not only the vivid colours, but also, almost, the very fragrance of the fruit.

Pekka’s workshop doubled as the family’s living room and library. It is a vast space, with the ambience of a wooden church interior. The exhibition seeks to recreate the studio’s distinctive atmosphere and visitors also have the opportunity to watch a video showing Halosenniemi as it is today (now a museum) and its surrounding landscape throughout the changing seasons.

At the 1900 Universal exhibition in Paris, Finland was awarded its own pavilion, a development that proved to be a crucial turning point for Finnish culture and the independence movement. Halonen was commissioned to paint two works, Laundry on the Ice and the Lynx Hunter, both of which are featured in the current exhibition. He brought two additional pictures to Paris, and for Winter Sunset (not included here) he was awarded a silver medal.

However, national romanticism was beginning to fall out of fashion in France, while in Finland the movement was going from strength to strength, with Halonen emerging as one of its most distinctive representatives.

Following the success at the Exposition Universelle, Halonen held his first solo exhibition in Helsinki. Increasingly, he focused on painting winter and early-spring landscapes. These snowscapes may appear typically Finnish, yet Halonen’s style was shaped by international influences. While studying in Paris, he wrote that he was impressed by the Japanese prints, as well as paintings by van Gogh and Puvis de Chavannes hanging on Gauguin’s yellow walls.

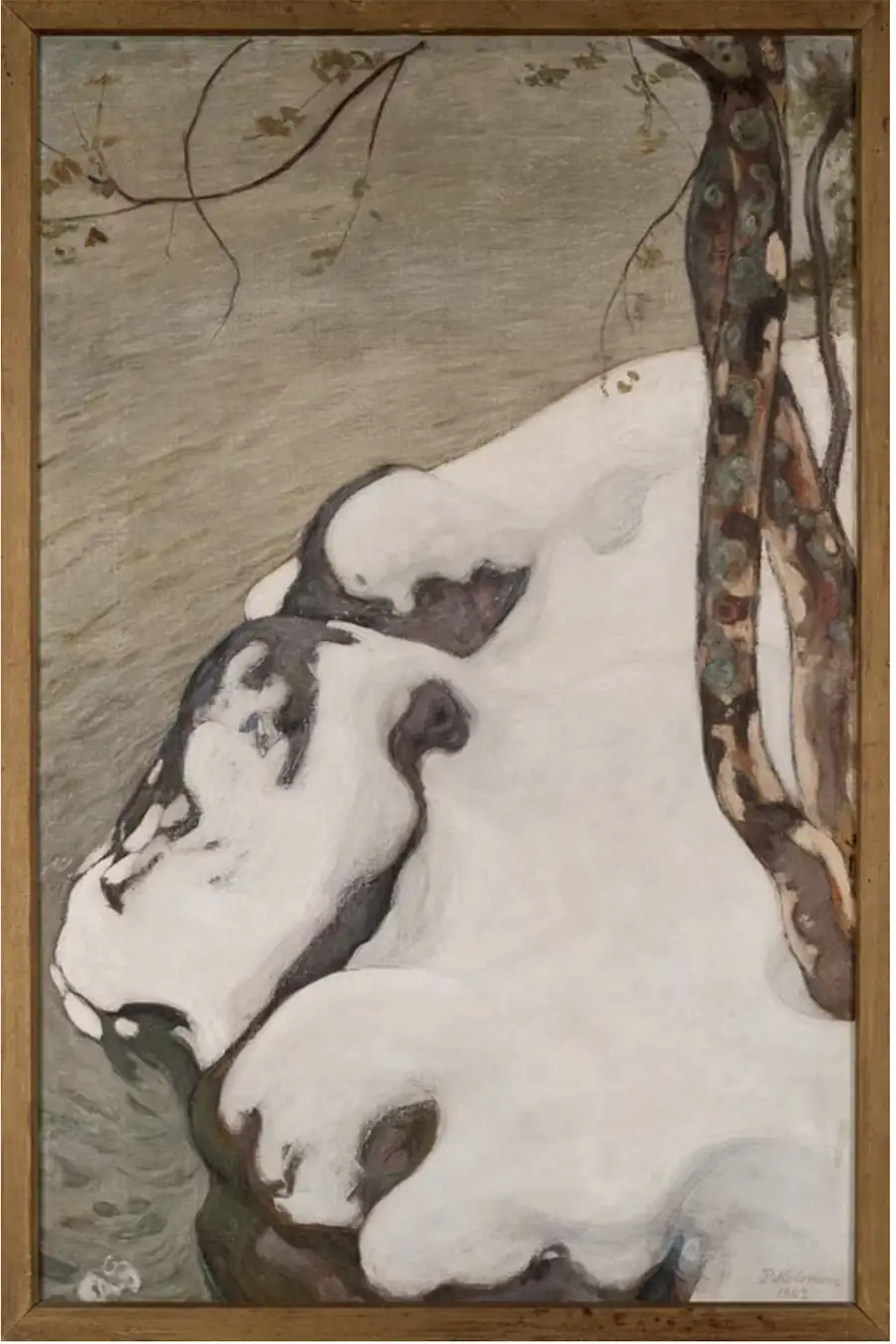

He began collecting Japanese woodcuts and assimilated many of their defining elements: cropped viewpoints, asymmetrical compositions, flattened surfaces, diagonal perspectives, and the high horizon lines. He also adopted the vertical elongated format of scroll paintings (kakemono) and the horizontal handscroll (makimono). When particularly satisfied with a finished work , Halonen would sometimes remark that it possessed a ¨Japanese vision¨.

The First Snow (1902) demonstrates all the hallmarks of japonism: no sign of the horizon, the outlines are clear, the composition lacks symmetry and the the snow contrasts with the dark earth beneath. The subdued colours enhance the quiet mood, which was a characteristic trademark in Halonen’s early snow landscapes.

It is rather curious that impressionism initially made so little impact on Scandinavian artists studying in Paris, despite their work being exhibited in the same galleries and their socialising in the same cafés as French artists. Finnish painters, in particular, were slow to adopt the latest French artistic trends.

The 1904 exhibition of Franco-Belgian Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art at the Ateneum Art Museum in Helsinki proved pivotal. Finnish artists began to experiment with, and incorporate into their work, the pure colour palette associated with Post-impressionist painters. Instead of depicting a plethora of heroic mythological figures, dark forests and sauna bathing, artists portrayed outdoor pursuits, such as nude bathing, sporting activities and endless summer days.

Halonen also paid a visit to the impressionist exhibition in Helsinki, though he was even more deeply influenced by a solo show devoted to Edvard Munch at the same institution (now the National museum) two years later. The progress is clearly evident in Birch Trees in the Winter Sun (1912). Halonen’s palette is much brighter, the trees cast mauve shadows, the brushwork is heavier, and he makes good use of impasto to convey the texture of the snow.

Halonen’s colour spectrum gradually broadened, and both his landscapes and interiors became increasingly luminous. The transition unfolds slowly, beginning with the introduction of primary colours. He livens up his snowscapes by introducing orange, yellow, blue, mauve or purple to the palette. More thought is also given to the rhythmic texture of the painted surface.

Towards the end of his life, Halonen clarified his working method in an interview:

¨Nature forms the framework of my paintings, but the atmosphere is the essence, the main part. Whether this atmosphere comes from the outside or from within me, I don’t really know. I prefer not to dwell on such questions, but one beautiful day I will find what I’m searching for, and then all I’ll have to do is capture it on canvas¨

There is a growing sense that Halonen begins to assign human emotions to nature – the Victorian art critic John Ruskin coined the term pathetic fallacy to describe the tendency to project feelings onto the workings of the natural world and inanimate objects.

In Halonen’s case this is not a weakness, as it propels him to move beyond the purely descriptive. A comparison of Snow-Covered Pine Saplings (1899) with Pine Tree in the Snow (1928) is quite revealing. The earlier painting is a well executed, naturlistic rendering of a young tree, its fragile branches bending under fresh, plump snow. Almost three decades later, Halonen, applying quick and broad brushstrokes, only narrowly avoids abstraction: the contorted shapes of the snow-clad pine on a sloping hill, set against a frozen, ochre-coloured frozen lake and horizonless background are only identifiable with the help of the title. Is it a frozen cry, perhaps an outpouring of grief following the sudden death of his elder brother Aapeli in 1928?

Halonen’s late works take on a more peaceful, intimate and introspective character. Although he occasionally returned to familiar places in north-eastern Finland, he no longer produced vast panoramas and was content to paint views in and around Halosenniemi. The house and studio should be regarded as Pekka’s and Maija’s Gesamtkunstwerk: a unified work of art combining music, archictecture, design and painting. Yet, Halosenniemi was first and foremost a family-oriented place where the couple raised their eight children, and where Pekka died in 1933.

The final room at the Petit Palais exhibition is painted in the deep ‘Pantone’ blue colour of the Finnish flag. It’s a nice touch, because all the paintings in this space are snowscapes, which stand out even more vividly against the blue walls. The Finnish flag itself consists of a white field bearing a blue cross.

Listen here to the French curator of Pekka Halonen, un hymne à la Finlande, Anne-Charlotte Cathelineau, as she explain how the organisers sought to immerse visitors in the spirit of Halosenniemi by recreating the atmosphere of the artist’s studio. She also expresses the hope that the video, showing the house and its surroundings throughout the seasons, will inspire people to one day visit the museum on the shore of Lake Tuusula.

Albert Ehrnrooth, December 2025

Pekka Halonen, un hymne à la Finlande

Petit Palais, Paris until 22 February 2026

Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede, the Netherlands

21 March 2026 – 16 August 2026

Ordrupgaard, Charlottenlund, Denmark

4 September 2026 – 10 January 2027