To put on a production of Henry Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas (1689 ) presents several challenges right from the outset. First, the musical sources are fragmentary. The earliest surviving scores date from 1775 or later and they lack enough material to fill an entire evening. The prologue featuring Venus and Apollo has been lost. Dido and Aeneas was originally set to music throughout –which was unusual in England. Some sections with just text have survived, but the music’s gone missing. The end of Act II would have featured a chorus and a dance, and dance music was almost certainly interspersed throughout the work.

Another, minor headache, concerns the role of the Trojan hero, Aeneas. Despite sharing top billing with Dido, he only has one aria, plus some recitative. To make the part more attractive to a first rate soloist, directors sometimes supplement the role with another, substantial aria.

Longborough Festival Opera managed to attract Bjarte Eike & Barokksolistene to oversee this special staging of Dido and Aeneas. It’s a coup , because the Norwegian ensemble have earned international acclaim for their Alehouse Sessions – semi-improvised concerts that recreate the bawdy and raucous musical styles that evoke the atmosphere one would have encountered in late-17th century London taverns. These sessions always feature songs by Purcell, and the ensemble has also been involved in Danish production of Dido and Aeneas. That production was directed by Erland Samnøen and featured a number of now well-known singers, including Mary Bevan in the title role and Rowan Pierce as Belinda.

At Longborough Samnøen has once more joined Barokksolistene, but this time he’s working with emerging artists from the opera house’s own training programme. While the cast is less experienced than the artists that featured in the Danish production, there is a lot of young talent on display.

But before delving into a review, a brief introduction to the plot of the opera.

Nahum Tate’s libretto draws on Book IV of Virgil’s Aeneid. Tate was mainly known for his peculiar revisions of Shakespeare’s plays – infamously he gave King Lear a happy ending and omitted the Fool.

Before the curtain rises on the opera, the widowed Queen Dido along with her sister Belinda, has fled the kingdom of Tyre and settled on the northern coast of Africa, where she has founded the city of Carthage. After the fall of Troy, Aeneas – a Trojan prince and demigod – flees, but he is shipwrecked near Carthage. Dido rescues him, and by the time the opera opens, she has fallen in love with him. But she hesitates to act on her feelings, fearing that romance might weaken her authority. Her sister Belinda encourages her to accept Aeneas’s proposal of marriage. At this point Samnøen introduces a new character: the local chieftain Iarbas. Although he doesn’t feature in Tate’s libretto, he is a figure from the classical Greek legend. Iarbas is the man who sold Dido the land on which she built Carthage, believing that in return he could claim her hand in marriage. Spurned by Dido, he conspires with an evil sorceress and her coven to break up the newlyweds. The sorceress summons a storm and sends a false messenger – disguised as the god Mercury– to remind Aeneas of his divine mission: to sail to Italy and found a new Troy. Aeneas orders his men to get ready to set sail for Italy, while the sorceress gleefully makes plans to wreck his voyage across the Mediterranean. Torn between love and duty, Aeneas tries to explain to Dido that he ‘s bound by divine command to sail to Italy. Though he offers to defy the gods and stay with her, Dido, wounded and proud, tells him to leave. He departs, and she is left to mourn his loss, and dies of a broken heart.

In Longborough, before the opera begins, the cast is introduced. Bjarte Eike then leads the audience in a singsong of the sea shanty Haul Away, Joe. We comply, because audience participation is a given with this ensemble. During the show Bjarte will also connect the dots between scenes, though it feels largely unnecessary. The music and the story are self explanatory and quite simple – especially if you pay attention to the songs, or read the lyrics that flash up on screens throughout the auditorium.

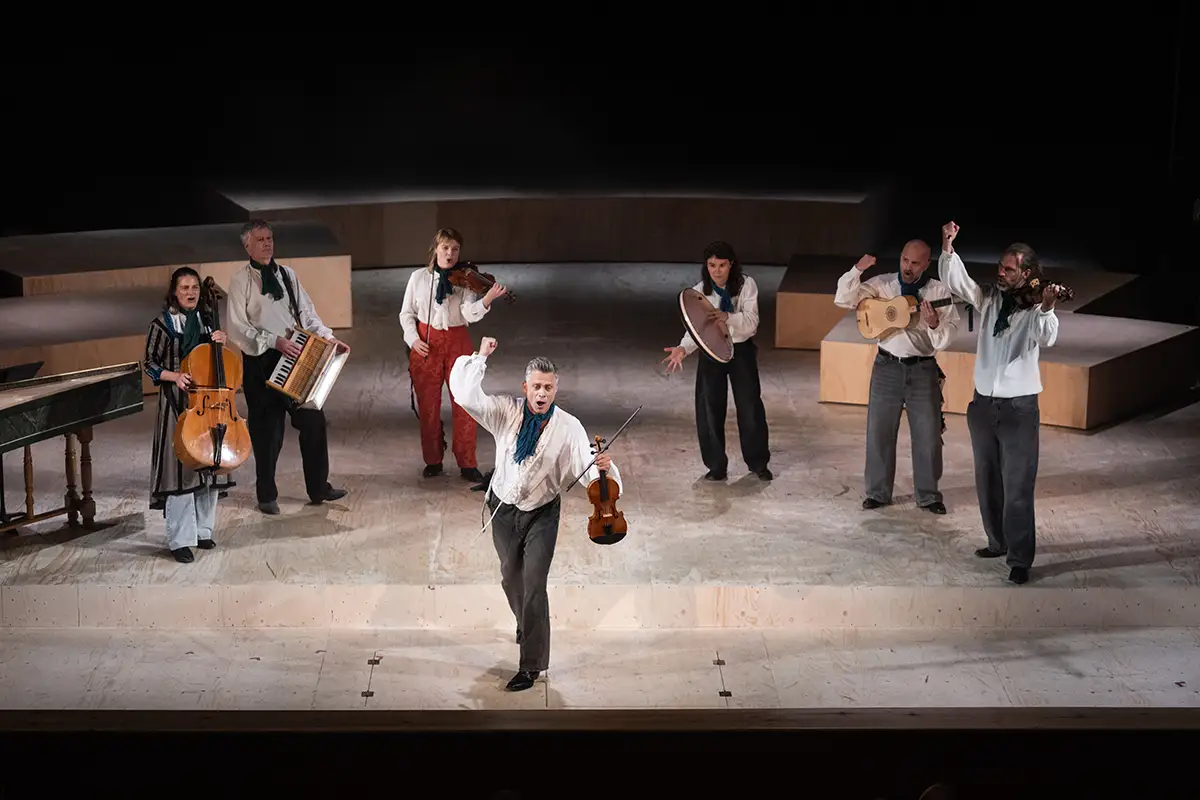

Bjarte Eike & Barokksolistene are the stars of the show. The ensemble consists of seven players: a string quartet, lute (or guitar), harpsichord (or harmonium ) and percussion. They perform entirerly from memory and remain on stage for nearly the entire opera. At times, they encircle a singer while accompanying them. But there are also moments when a soloist is backed by just a lute, theorbo or violin, lending every song an intimate and and spontaneous quality.

You begin to sense how closely Purcell’s music remains tied to folk music traditions – in this case particularly the Norwegian spelemann tradition – which roughly corresponds to ‘fiddle music’. True, wind instruments don’t feature, but during the performance it I didn’t miss them for a moment.

Sam Young (Aeneas) has already sung several substantial roles with smaller opera companies. His baritone is warm and pleasant, but his portrayal of the Trojan hero would benefit from more distinctive characterisation. After all, we’re dealing with a half-god – think super hero. And what kind of man abandons his newly wedded wife?

The Sorceress, Dido’s antagonist, is sometimes sung by the same performer as Dido. Mezzo-soprano (or perhaps a contralto?) Lydia Shariff bravely embraces this ‘super-witch’ role with gusto and a dash of humour, while steering clear of pantomime. Jasmine Flicker (Belinda) is also shaping up to be a fine soprano – and unexpectedly a talented violinist as well! Among the supporting cast (cousin, witches and sailors) there’s also a wealth of potential and you get a strong sense of a ensemble effort.

It certainly helps that Camilla Seale (Dido) has the graceful and regal bearing of a baroque queen, but it’s her voice – its lustrous sheen and natural vibrato – that convinces me that she’s going places. Though a mezzo soprano, I hear the qualities of a (future?) high contralto.

It’s the chorus – not Bjarte Eike!! – who are tasked with moving the narrative forward, and the Longborough Youth Chorus accomplishes this admirably.

The Iarbas character, inserted by the director, ultimately felt superfluous – a distraction rather than a meaningful addition to the drama. Similarly the spoken quotations from Shakespeare and others, felt like a disruption rather than enriching the flow of the action.

¨Death must come when he is gone¨, sings Dido, before we are treated to one of the most exquisite and moving endings in all of opera. Camilla Seale is unforgettable as she pleads: ¨Remember me , but ah! Forget my fate¨. The chorus then sums up, and draws the tragedy to a close. The staging of the final scene is magical, as everyone slowly lies down on the ground. I would have been content if it all ended there.

But no, Bjarte Eike insists we stay for ‘Dido’s wake’. Each of the young soloists is given a turn, with songs ranging from the folk classic ‘ If I were a blackbird’ to sea shanties, and God knows what. It’s excessive and feels totally disconnected from the compelling and enjoyable interpretation of Purcell’s masterpiece we’ve just experienced.

The encores add nothing. Just cut them, please.

Albert Ehrnrooth

You can find out more about the Longborough Opera Festival here