The exhibition Gallen-Kallela, Klimt & Vienna at The Finnish National Gallery suggests that Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s more mature mythical style was influenced by his encounters with the Viennese Secession movement. His paintings, it’s hinted, in turn made an impact on Gustav Klimt’s work. Yet in my two catalogues from Gallen-Kallela retrospectives – and even in the publication from the artist’s own museum – his three visits to Vienna are only mentioned fleetingly. In Klimt scholarship there are no, or very sparse, references to one of Finland’s greatest artists.

Did Vienna, the Viennese Secession movement and Wiener Werkstätte have a significant effect on Finnish architecture and design? And did Klimt’s decorative symbolism and eroticism, Koloman Moser’s innovative designs and paintings and Egon Schiele’s expressive, psychological style really resonate with Finnish painters at the beginning of the 20th century?

The answer is both yes and no.

A number of Finnish architects – particularly Eliel Saarinen and much later also Alvar Aalto – were deeply influenced by Viennese Art Nouveau, known as Jugendstil or Viennese Secession. There is no doubt that Wiener Werkstätte’s core values – its emphasis on handcraftmanship over mass production, its clean geometrical designs, and its philosophy of harmoniously integrating the applied and decorative arts – made a profound impact on Finnish modernist design.

But no, when it comes to the Viennese Secession painters I wasn’t aware that they had a direct influence on their colleagues in Finland. Clearly, I may have been mistaken. Or perhaps not?

Gallen–Kallela grew up on a farm in Tyrvää in southern Finland. His parents experimented with fairly exotic crops, but his mother was also a keen amateur artist who encouraged her son’s artistry. He was sent to secondary school in Helsinki, where he attended evening classes in drawing and crafts. At 16 he began full-time studies at the Finnish Art Society and took private lessons with a skilled genre painter.

In the 1880s Scandinavian painters were flocking to Paris, and Gallen-Kallela followed suit in 1884 to study at both the Académie Julian and Atelier Cormon. Although he found some of the tuition outdated, he made many new friends, and participated in several Salon exhibitions. At the 1889 Paris Exposition he unveiled his first major Kalevala-themed painting – the first version of the Aino Myth triptych – which earned him a silver medal. A second version on the same theme was completed two years later. The frame, also designed by Gallen Kallela, features quotes from Kalevala – Finland’s national epic –and therefore can be regarded as a Gesamtkunstwerk, uniting three artistic disciplines. The Viennese Secession artists aimed to merge fine arts and applied art into a single, unified total work of art.

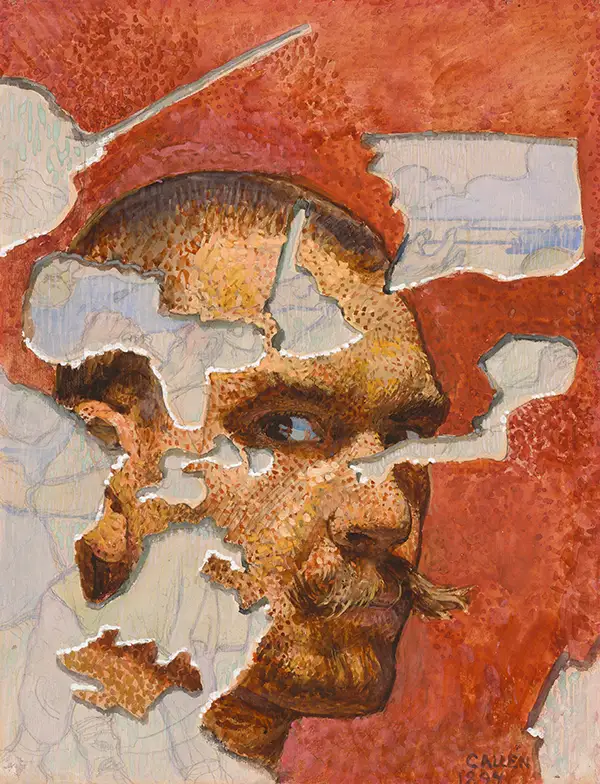

Gallen-Kallela’s Paris stint came to an end in 1889 when he moved back to Finland and married Maria Slöör. A year later their first child, Marjatta, was born. He began taking on students and started planning the construction of Kalela, which became the family’s home and the artist’s studio in 1895. This peaceful retreat in Western Finland, shaded by pine trees, stands today as a museum – a lofty log house with high ceilings, stained glass, textiles and furniture all designed by the couple themselves. Here on the shore of Lake Ruovesi, Gallen-Kallela created a home, an ideal space for painting and an architectural expression of a total work of art. Up to this point there is no evidence of Viennese influence on Gallen-Kallela’s work. His years in the French capital had brought about a stylistic shift towards Symbolism and Synthetism, yet he never fully abandoned the traditions of realistic portraiture.

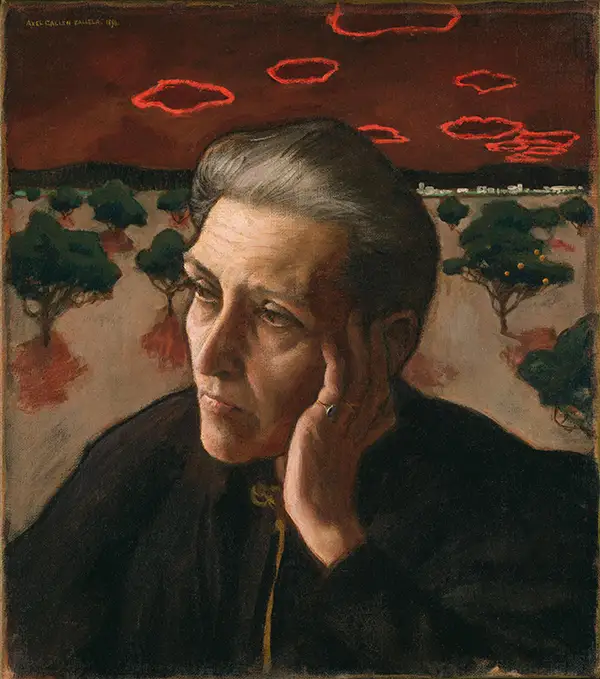

The exhibition features several works from the early part of Gallen–Kallela’s career. I consider Lemmikäinen’s mother (1897)– for which he had his own mother pose – to be one of his most moving interpretations of a scene from the Kalevala. The previous year he had portrayed his mother, Matilda, deep in thought within a mystical landscape of red clouds and rhythmically spaced trees, alluding to her interest in theosophy and spiritualism. The Artist’s Mother is a masterpiece from Stockholm’s Nationalmuseum that would not look out of place in a gallery of Italian or German Renaissance portraits.

Gallen-Kallela was acutely aware of his restlessness and Wanderlust. In 1895 he suddenly decided to travel to Berlin, where he reconnected with friends, exhibited alongside Edvard Munch, sold a few works and studied printmaking. His stay was cut short by the sudden death of his daughter, but a month later he was back in Berlin and soon continued on to London. There he spent time studying Irish manuscripts at the British Museum and purchased a printing press. William Morris and the Arts & Crafts movement– with its ideals modeled on medieval and folk art – made a strong impression on the young Finn. For the next two years following his visit to London, he experimented obsessively with different printmaking techniques. Particularly his woodcuts, but also other graphic works from this period show the influence of Dürer and Japanese Ukiyo-e woodblock prints and, above all, Aubrey Beardsley’s highly stylised black ink drawings.

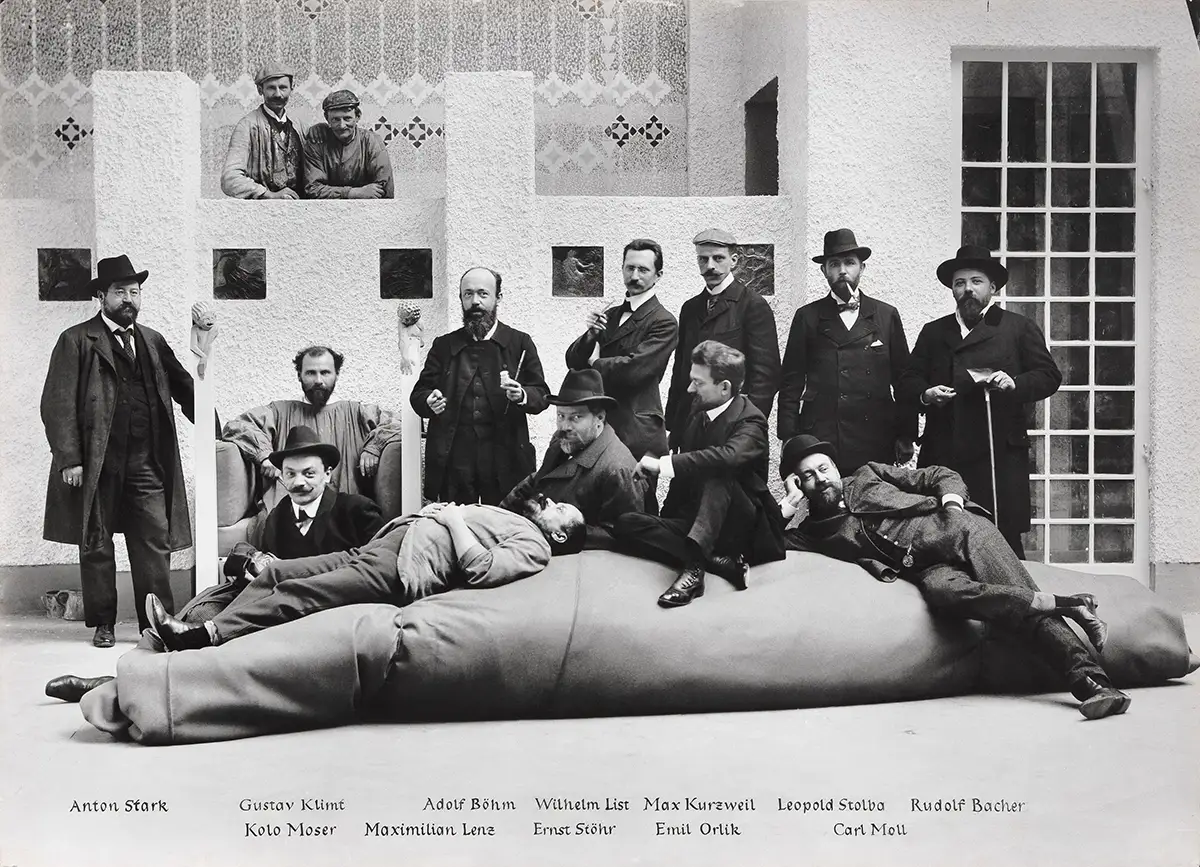

In 1897 a group of artists, designers and architects – including Gustav Klimt, Otto Wagner, Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser – decided to break away from the stifling academicism and historicism that still dominated Vienna. The group, soon adopted the Wiener Secession label, took their cue from their rebellious colleagues in Munich and Berlin, and set out to present the latest international trends. Klimt and Moser initially emulated the curvilinear Jugendstil that had originated in Munich, but soon developed highly individual styles of their own. In 1903 Hoffmann and Moser established the Wiener Werkstätte, which evolved out of the Secession group and focused on the applied arts. The Viennese workshop became the cradle and an enduring source of inspiration for the Modernist, Bauhaus movements and, a few decades later, Scandinavian design.

At the Munich Secession exhibition in 1898 Gallen-Kallela’s The Defence of Sampo garnered a lot of praise. He was subsequently commissioned to paint four Kalevala-themed frescoes and design the furnishings for the Finnish Pavilion at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris. It was a huge success – he won a couple of medals – and it’s hardly surprising that the following year, on the recommendation of the patron and ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev, his works was given a prominent place in the Vienna Secession’s large-scale Nordic exhibition. Ver Sacrum, the movement’s official magazine, even visited Gallen-Kallela’s studio-home-Gesamtkunstwerk in Ruovesi, resulting in a lengthy article on the artist’s idiosyncratic approach.

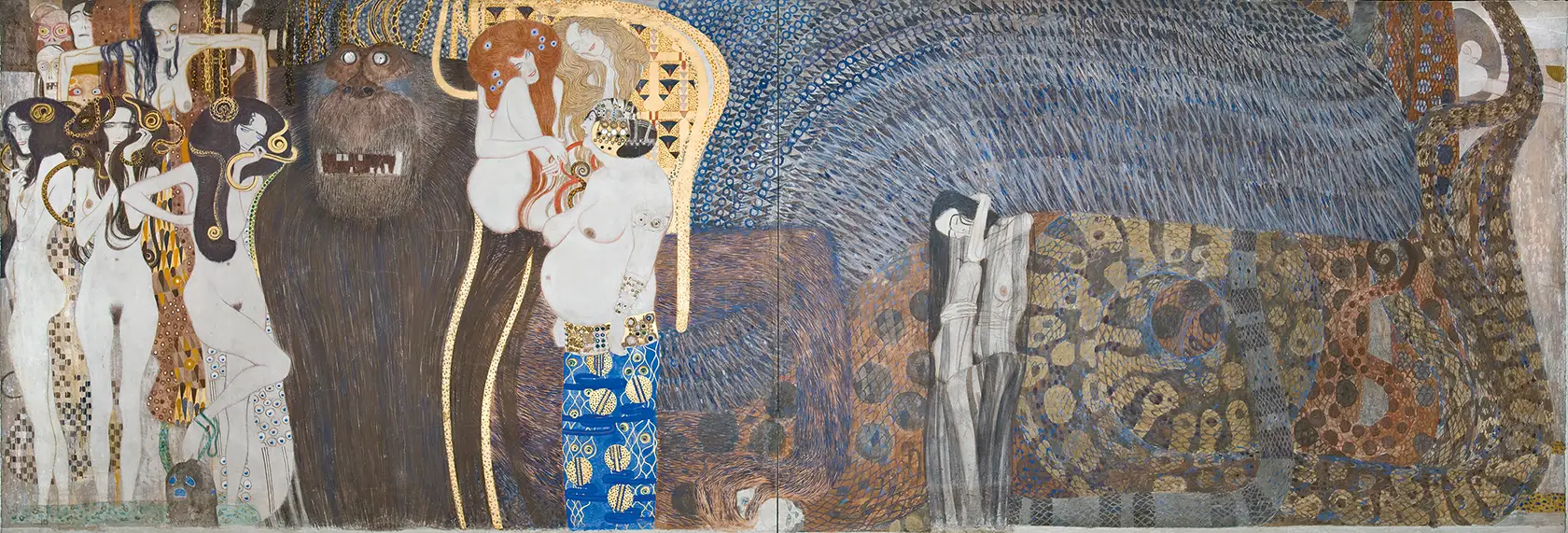

Klimt was working on his Beethoven Frieze while Gallen-Kallela was in Vienna and it’s possible that he visited the artist’s studio. Inspired by Richard Wagner’s 1870 essay on Beethoven and his Ninth Symphony, Klimt created a ‘temple’ to the composer in Joseph Maria Olbrich’s imposing Secession building. The recreation of this space is one of the highlights of the exhibition. Klimt’s two-dimensional depiction painted on three plaster walls features a golden knight in armour, petitioned by ‘suffering humanity’, taking up the fight for happiness. The central wall shows Typhoeus, the monstruous winged ape, accompanied by three Gorgons and some other ‘hostile forces’. On the third wall – which originally had an opening that revealed Max Klinger’s Beethoven sculpture – Klimt’s vision of the Ninth Symphony’s 4th movement –with Beethoven’s setting of Ode to Joy – culminates in pure joy and happiness, and finally a naked pair of lovers kissing. It’s all terribly convoluted, but this marvelously decorative work ushered in Klimt’s much loved ‘Golden Period’.

So, Gallen-Kallela could have seen this masterpiece and according to the exhibition catalogue, what he and Klimt had in common was :¨the belief that the modern world needed myths as a reminder of timeless truths¨.

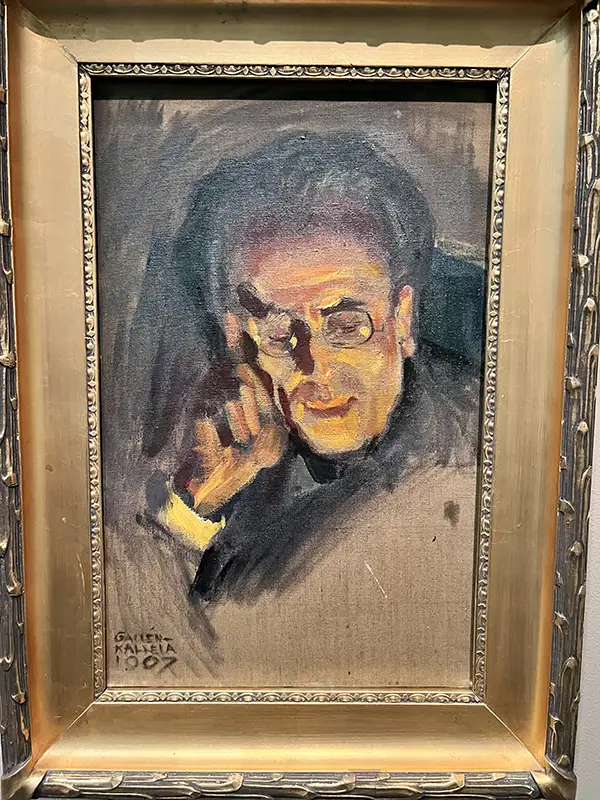

Gallen-Kallela did make quite an impression at the Secession’s Nordic exhibition in – in particular his depiction of the roaring rapids in Imatra and the monumental Kaleva ‘fresco-like’ paintings. He was immediately invited back and in the spring of 1904 he exhibited eleven more works in Vienna. Four were sold to the steel magnate Karl Wittgenstein, who later passed them on to his sons: the concert pianist Paul and the famous philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Gallen-Kallela spent several months in the city and enjoyed himself so much, exploring Vienna’s cultural delights, that he insisted Mary join him. The couple were introduced to Gustav Mahler, who was at the time the Hofoper’s director, and he offered them the use of his personal box at the opera house. Mahler visited Finland in 1907 on which occasion he had an often quoted conversation with Sibelius. Less known is Gallen–Kallela’s portrait of the composer-conductor, and it is thought it was painted at Hvitträsk, the studio home of the architects Gesellius, Lindgren and Saarinen built in National Romantic style. Portraits of Mahler, painted during his lifetime, are exceedingly rare.

Vienna was a meeting point for the arts around the time the Secession movement and the Wiener Werkstätte reached their zenith. As Europe’s fourth-largest city, Vienna was not only a vibrant centre for artists, architects, and designers; it was also the birthplace of the Second Viennese School — the twentieth century’s most innovative musical movement, in which Arnold Schönberg, Anton Webern, and Alban Berg broke with tradition, embracing atonality and developing the twelve-tone technique.

Admittedly, there are striking parallels between Klimt’s On Lake Attersee (1900) and Gallen-Kallela’s Lake Keitele series (1904 – 06). The paintings are square in format, depicting a wide expanse of water, a narrow band of sky (high horizon), and there are also similarities in brushwork technique. There’s no evidence, but Gallen-Kallela may have seen Klimt’s On Lake Attersee. Yet where Klimt moves towards abstraction, Gallen-Kallela wanted to evoke something more mythical – the wash of Väinämöinen’s boat (which has disappeared out of the picture) on the lake. The Russification campaign under Tsar Nicholas II was coming to a head and Gallen–Kallela was in a subtle way using the bard from Kalevala epic as a source of national pride. Gallen-Kallela was painting a ‘typical’ picturesque Finnish lake that would please the tourist view, while make a political statement to his home audience.

Koloman Moser’s Wolfgangsee with High Horizon (1913), just like Klimt and Gallen-Kallela, flattens space, picturing a tranquil lake that reflects the soft purple afternoon light on the mountains. However, Moser was deeply influenced by the Swiss painter Ferdinand Hodler’s alpine and mountain landscapes.

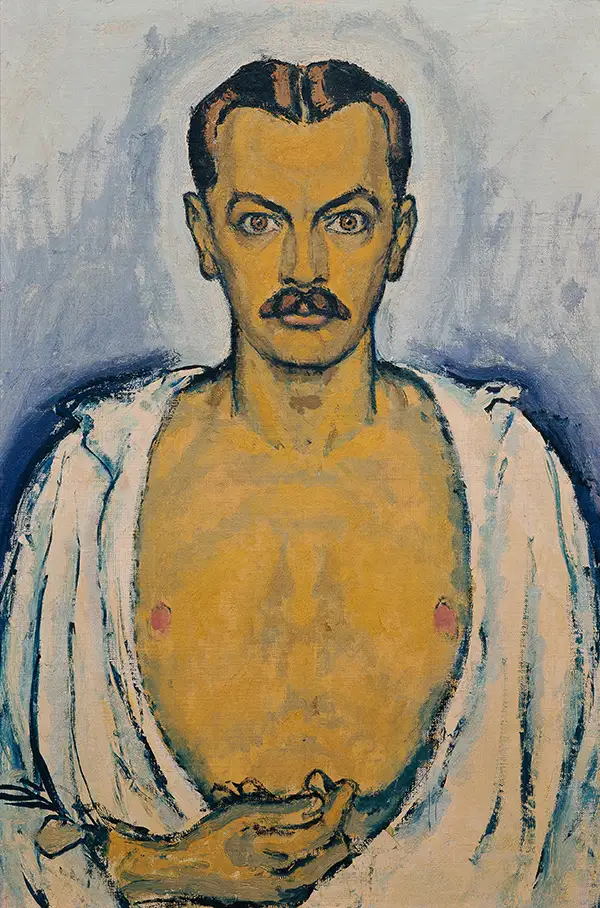

In Moser’s Self-portrait (1916-17) the artist’s gaze is fixated, apparently staring at the viewer. Or is it? Knowing that Moser was suffering from terminal cancer, it seems more likely that he is looking inward. He draws on Christian iconography, specifically the Man of Sorrows (imago pietatis), a devotional image showing Christ with a bared chest.

A truly multi-talented artist, Moser also created playful and innovative designs for furniture, ornaments and posters, revealing a rich imagination that also defined his painting.

Egon Schiele, mentored and early on influenced by the much older Klimt, is represented in this exhibition by only one major work by – regrettably not one of his emaciated, often sexually unsettling nudes. No Finnish artist adopted Schiele’s feverish expressionism, yet his influence was likely felt indirectly, though only decades after his death.

iFinnish readers of early 20th-century art journals were well aware of the Wiener Werkstätte. Gustaf Strengell, curator at the Museum of Applied Arts, visited Vienna and wrote several articles for Finnish journals, focusing on the architect and designer Josef Hoffmann’s utilitarian aesthetic, which favoured clean, geometric ornament. The Finnish architect Rafael Blomstedt even worked in Hoffman’s practice. When he later became artistic director of the Central School of Applied Arts – housed in the same building that now contains the Ateneum museum – he introduced the Viennese workshop’s ethos to Finland.

The trio Gesellius, Lindgren, and Saarinen were leading advocates of Finnish National Romanticism, a movement that evolved from the Arts and Craft movement and Jugendstil . This exhibition presents them as Nordic counterparts to the Vienna Secession’s total-design ideal. The villa Hvitträsk – designed by the Finnish trio – embodies the Wiener Werkstätte’s holistic approach, integrating architecture, furnishing and textiles, down to the smallest detail. In the 1920s Eliel and his wife Loja Saarinen transposed this spirit to the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, where their modernist pedagogy reflected the philosophy championed by Wiener Werkstätte.

Most of the paintings by Akseli Gallen-Kallela – known as Axel Gallén before he Finnicized his name in 1907 – will be familiar to Finnish visitors. Yet that’s no reason for not visiting: the Belvedere Museum in Vienna has generously lent works by Klimt, Moser and lesser-known artists like Broncia Koller-Pinell and Carl Moll (who became Alma Mahler–Werfel’s stepfather !).

Although the Viennese Secession movement ‘s influence on Finnish artists was more conceptual than explicit, this exhibition offers a rare opportunity to experience art seldom seen in Nordic museums.

More information about the exhibition ‘Gallen-Kallela, Klimt & Wien’ you can find here