Can there really be a production of Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro that is, in nearly every respect, perfectly staged and superbly sung? I wouldn’t have believed it myself – until I recently experienced Opéra National de Paris’s performance of the masterpiece at the wonderful Palais Garnier.

Le Nozze di Figaro (1786) makes formidable demands on the singers and the orchestra. Its intricate plot moves often at great pace and can be tricky to follow if you haven’t read the synopsis beforehand. And yet, despite these challenges, the opera is today more popular and performed more frequently than ever.

Johannes Brahms wrote: ¨Each number in The Marriage of Figaro is for me a marvel; it is simply incomprehensible how anybody could create something of such an absolute perfection. Never has anything like this been made, not even by Beethoven.¨

Netia Jones is the set designer, costumier and director (!) of Opéra National’s production and she places the action backstage at the Palais Garnier, Europe’s most opulent and storied opera house (known to many through The Phantom of the Opera). It’s a brilliant move because the building, designed by Charles Garnier, is a ¨grand spectacle¨ in its own right. The Figaro souvenir programme suggests that the edifice’s ¨splendour resembles an allegory of political and male power¨. That may be debatable, but the The Marriage of Figaro‘s central themes – love, infidelity and forgiveness – are universal and never feel dated. The underlying themes of hierarchy, power and above all gender dynamics, however, certainly lend themselves to reinterpretation.

It no longer makes much sense to stage The Marriage of Figaro in its original period. It’s hard for a modern viewer to appreciate the explosive impact Beaumarchais’ original play, La Folle Journée, ou Le Mariage de Figaro had on its first audiences. Louis XVI attempted to ban the play, but he was less troubled by its mockery of the nobility and their perceived privileges than by its ¨revolutionary’ challenge to the social order. With hindsight, one could argue that Beaumarchais’s sharp criticism anticipates the social upheavals of 1789. Ironically, the king’s own aristocratic courtiers persuaded him not to censor it too heavily.

During the three years in which the play was left in limbo (1781- 1784) Beaumarchais organised numerous readings in Parisian salons and launched what today would be described as a highly successful media campaign.

The play finally premiered in Paris five years before the French Revolution and caused a stampede at the ticket office. In Vienna Emperor Joseph II heard about the controversy and public disorder the play had caused in Paris. Despite his reputation as an enlightened absolutist, he banned it from the stage, permitting only its publication. Joseph had recently commissioned Die Schauspieldirektor from Mozart and after the obvious political content was removed from the operatic libretto, Lorenzo Da Ponte, then employed at the imperial court, managed to secure approval for Figaro.

Figaro was created before the Revolution and before industrialisation totally changed the economic and social landscape. ‘Elective aristocracy’ was being debated, but democracy and women’s suffrage remained little more than pipe dreams. In fact, most women still lived under male tutelage.

THE REVIEW

Mozart chose D major as the home key, and already in the overture he signals the opera’s exalted, grandiose and energetic character. One senses that the Orchestra de l’ Opéra National is raring to go, but conductor Antonello Manacorda is in no rush and adopts sensibly judged tempi, informed by the fact that he has conducted The Marriage of Figaro more often than any other work. Music and singing come together beautifully throughout the production.

During the overture Bartolo (James Creswell) and a young ballet dancer cross the stage from opposite sides, and as they pass, he pinches her bottom. The tone is set.

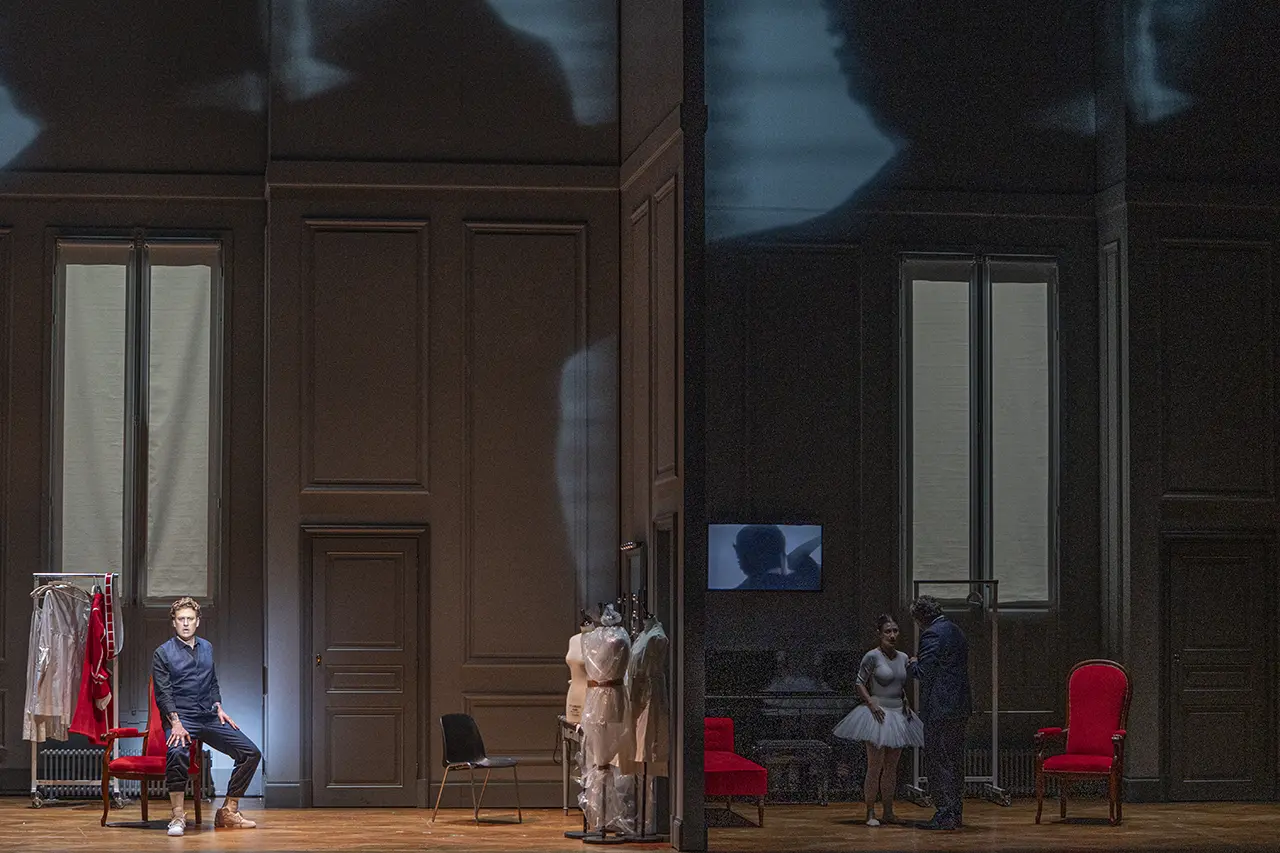

As the curtain rises we discover three separate rooms connected by doors, presented in a contemporary backstage setting. Susanna (Sabine Devieilhe) is a wardrobe assistant, while Figaro (Gordon Bintner) is in charge of wigs – appropriate enough, given that he is the former barber of Seville. Il Conte Almaviva (Christian Gerhaher) appears as the actor-manager, while the Contessa (Hanna-Elizabeth Müller) is the leading lady of the theatre company. The transposition from Count Almaviva’s estate to the world of the theatre works surprisingly well, and Don Basilio (Leonardo Cortelazzi), the music teacher, scarcely needs to pretend to be anything else.

The setting is modern, yet the ‘actors’ are getting ready to perform in 18th century costumes. In the opening scene Susanna asks Figaro to comment on her bonnet; however, he is too preoccupied with measuring the room the Count has allocated to the couple. Susanna points out that installing a bed next door to the Count’s office is a bad idea, as it would make it all too easy for him to have his way with her. (She appears to have succeeded, because there’s no bed anywhere in this production)

In a delightful duet – Se a caso Madama – with her husband-to-be, Susanna explains that the Count will send Figaro on an errand and then summon her by ringing the bell that makes a ‘dong-dong’ sound. This is unintentionally amusing for fluent English speakers, as ‘dong’ is a slang term for the penis.

Figaro – not the sharpest tool in the shed – has been completely unaware of the Count’s lewd behaviour towards his bride, but in the famous cavatina Se vuol ballare vows to take action. The baritone Gordon Bintner has the physical stature, poise and the strong voice of a determined man, yet Figaro’s plans repeatedly come to nothing. A case of brawn over brains? Perhaps, but at least he remains faithful. Fortunately, Susanna is smart enough to maintain her dignity, safeguard her impending marriage, and teach the men a lesson. Sabine Devieilhe’s comic timing is excellent, and she portrays an agile, quick-witted woman who understands that flirting can be a useful tool. Devieilhe is a light coloratura soprano, endowed with a crystalline voice whose pure lustre is completely at home in the gold decorated Garnier auditorium.

Meanwhile, the Count is in the room next door, ostensibly interviewing a ballerina; before long he is taking liberties and dancing with her (to the tune of Se vuol ballare!). These unscripted, not too distracting, silent goings-on – of which there are several in the first two acts– unfold in the two rooms adjacent to the main action. #MeToo activists have highlighted how common sexual assaults used to be in the entertainment industry.

The Count has already worked out a plan to prevent Figaro from marrying Susanna, so that he can claim his ‘legal right’ – Droit du seigneur – to take her virginity. Figaro is in trouble, having borrowed money from the Count’s middle-aged housekeeper Marcellina; the contract stipulates that if he cannot settle his debt that very day, he must marry her instead. The baritone Christian Gerhaher uses his great versatility and unblemished, dignified intonation to make the Count – at least in the first two acts – somewhat tolerable. He was, after all, in The Barber of Seville, the prequel to Figaro, quite a likeable character.

When the villagers arrive – encouraged by Figaro – to sing the Count’s praise for having abolished the ancient practice of Droit de seigneur – they carry with them leaflets condemning sexual harassment. To show his support the Count – at his hypocritical best – puts up a few of the posters himself.

Enter Cherubino, the Count’s page and the Countess’s godchild. This is humorous gender juggling at its best and one of the best, if not the best trouser role ever written. Lea Desandre’s Cherubino is a badly dressed (red tracksuit), cheeky, guileless and yet vulnerable adolescent. He is easily sexually aroused, and admits to Susanna that he can’t help flirting with every girl he meets, including her. His aria Non so piu cosa son, cosa faccio requires both breathless articulation and seamless legato control – not forgetting the masculine physicality of the role. Desandre meets these challenges with ease, aided by a natural, almost shimmering, vibrato. You immediately feel how much she relishes this showpiece of a role for a young opera singer.

Cherubino was earlier caught with the gardener’s (underage) daughter, and now the Count overhears gossip that the boy is madly in love with the Countess. This fuels his jealousy and anger and he banishes Cherubino to the army.

Act II opens with the introduction of the Countess, resplendent in an eye-catching hoop skirt, lamenting her husband’s infidelity. Hanna-Elizabeth Müller delivers the deceptively challenging cavatina Porgi, Amor with heartfelt conviction, rooted to the spot. It is a kind of torch song – an aria for all aggrieved women that still long for their unfaithful husband’s return. There’s another reason why Hanna-Elizabeth Müller doesn’t move; when the short aria is finished, Susanna emerges from beneath the Countess’s skirt – eliciting a big laugh from the audience.

The second act is where every main character gets drafted into one of the opera’s overlapping plots and counter-plots.

Figaro has heard that the Count intends to prevent his marriage by supporting Marcellina’s legal claim against him. Figaro has devised his own cunning plan to thwart his boss; Basilio is to deliver an anonymous letter warning the Count that the Countess will meet her lover at the ball that evening. Meanwhile, Susanna’s scheme is even more ingenious. Cherubino is to dress as Susanna for a secret rendezvous with the Count in the garden, allowing the Countess to catch her husband in the act and embarrass him.

The act is also brimful of glorious tunes, most famously Voi che sapete. Susanna persuades Cherubino to perform the love song he’s written especially for the Countess. Desandre’s Cherubino is too shy at first to face her intended audience. The Countess is visibly moved by the overwhelmed, yet sweet-voiced teenager. Susanna then dresses the bewildered Cherubino as a younger version of herself. The farce begins in earnest when the green-eyed Count is heard knocking at the door, convinced that his wife is hiding a lover. Cherubino panics and jumps out of the window without the Countess’s knowledge. Under pressure from her husband The Countess confesses that Cherubino is hiding in the dressing room – only for Susanna to emerge instead, baffling the Countess and embarrassing the Count, who is forced to beg his wife’s forgiveness.

The Act II finale is magnificent in every respect. We have already heard duets and trios, but Mozart continues to expand the ensemble still further. Never before had he matched instrumental colour so perfectly to the emotional shifts and the farcical actions unfolding on stage. He exploits his musical arsenal to the fullest; linking numbers, dispensing with recitatives and – together with Da Ponte– mocking the very concept of a grand second-act finale, by exaggerating it even further. Conductor Anotello Manacorda has his work cut out, but interpreting his busy, dancing arm movements, clearly visible from the stalls, tell me that he’s enjoying himself.

Figaro joins the Count, Countess and Susanna, but things turn tumultuous when the gardener Antonio bursts in, complaining that he saw a man thrown down from the balcony. Worst of all, the culprit destroyed the carnations and a flowerpot. Figaro attempts to take the blame for the incident in the quartet Signori, di fuori. The situation grows even more confusing with the arrival of Basilio, Bartolo and Marcellina, who is pressing her claim on Figaro. A marvelous septet enfolds. The Count will investigate and preside as judge. Figaro’s wedding has been delayed once more.

There’s a major set change in Act III. Upstage we see cross-over catwalks that are used in a grid-less fly tower. Hundreds of 18th century garments hang from extended clothes rails and lighting rigs. Susanna is fitting the Count with an 18th century frock coat. It is very clever staging: the act of dressing requires intimate proximity. Susanna promises to see the Count in private, and he can scarcely believe his luck. Sabine Devieilhe adopts her sweetest manner as she makes the final adjustments to the coat. When she leaves, she bumps into Figaro and tells him that they have won their case (and freedom to marry). The Count overhears the exchange and realises that he is being deceived. Christian Gerhaher scolds the ¨half-wit¨Figaro in his vengeful aria Hai già vinta la causa dressed in a flared frock coat, strutting like a cuckolded rooster, tail proudly aloft. Gerhaher goes for it and lets his voice rip.

The Count summons Don Curzio, Bartolo and Marcellina to confront Figaro and inform him that it is time to pay up or marry. Figaro counters that he needs his parents’ consent to marry and he can’t find them. It doesn’t take long for Marcellina to realise that he is, in fact, her long-lost son, stolen from her as a baby. Bartolo turns out to be his father. When Susanna arrives, she finds mother and son locked in an embrace, unaware of the true relationship that has just been uncovered. The misunderstanding gives rise to the delightfully funny sextet: Riconosci in questo amplesso.

Meanwhile the Countess is uncertain whether she should go through with a plan devised by her servant – well, her dresser in this case – which requires her to exchange clothes with Susanna. ¨Oh heavens, to what humiliation am I reduced, by a cruel husband……..now forces me to seek help from my servant!¨, she sings. She’s hardly a model representative of the modern woman, and certainly not the Constant wife of W. Somerset Maugham’s novel. No, she’s still ¨yearning for him always¨ – the Count that is. Yet it is worth remembering that her role in the opera is to be forgiveness personified. Even so, we hear her sorrow almost crushing her love for the Count in Hanna-Elisabeth Müller’s very measured and sophisticated interpretation of Dove sono i bei momenti.

This deeply affecting scene is followed by ever more ingenious schemes and entrapments. The Countess dictates a letter to Susanna inviting the Count to a tryst. Barbarina, who has allowed the Count to ¨kiss and hug¨ her in exchange for ¨anything you want¨, now claims her reward: Cherubino. She plans to dress her beloved as a girl so that he can mingle with peasant girls presenting flowers to the Countess. It’s all for naught as the gardener immediately recognises Cherubino. Figaro invites everyone to dance, and while a troupe of young ballerinas from the Paris Opera Ballet lends some class to the march and the fandango, Susanna slips the ‘secret’ note to the Count.

By the time Act IV arrives, Mozart has exhausted his very finest tunes. But second-rate Amadeus can still be world-class, and even a near-perfect opera can have its weaker moments.

Barbarina’s opening cavatina, L’ho perduta …me meschina is a simple– and admittedly somewhat pointless – little number, but it nonetheless deservedly puts Ilanah Lobel-Torres in the spotlight for a few minutes.

Marcellina’s Il capro e la capretta musically doesn’t rank among the top ten arias of Figaro, but the premise of Netia Jones’ production can be found in its text. By now, the fundamental concept has been established, yet to underline it further the crucial lines from the recitative and aria are projected on to the wall behind Marcellina: ¨Every woman is bound to come to the defence /of her own poor sex/So put upon by these ungrateful men¨

Monica Bacelli injects the aria not only with biting humor, but also with a conviction I’ve never seen before in this minor role. Even if we don’t go home whistling a melody from the opera, we will certainly not forget the message Mozart, Da Ponte and Netia Jones wished to convey: ¨But we poor women,/who love these men so much,/ are always treated with cruelty by the perfidious creatures¨.

Sabine Devieilhe (Susanna) is also a very seductive Countess, in disguise

Sabine Devieilhe (Susanna) is also a very seductive Countess, in disguise

But of course, the opera doesn’t finish there. Figaro now suspects his bride of cheating on him, denounces the faithlessness of women, and decides to spy on Susanna. Warned by Marcellina she takes mischievous pleasure in winding him up with the seductive aria Deh Vieni, non tardar, o giois bella pretending not to notice him. Sabine Devieilhe turns into a delightful little minx, while the accompaniment adopts the musical style usually reserved for the Countess. Next Susanna and the Countess switch roles. Cherubino flirts with the Countess, believing her to be Susanna, while the Count gets amorous with his own wife thinking its Susanna. Meanwhile Figaro has recognised his wife despite her diguise, and, in revenge, pretends he is chatting up the ‘Countess’. This drives Susanna mad and Figaro is on the receiving end of some of decidedly kinky slapping, and appears to enjoys it.

They soon reconcile and decide to outwit the Count, who believes he’s caught his wife canoodling with Figaro. In a jealous rage he calls his men to arms, and when Figaro and Susanna – still masquerading as the Countess – beg for forgiveness, he refuses. Then the real Countess emerges. The Count is humiliated and begs his wife’s pardon. She is ¨kinder¨(piu docile io son) and forgives him unreservedly.

The company lines up for the final grand finale, a joyous, almost hysterical quick march, proclaiming: ¨ln contenti e in allegria /Solo amor può terminar¨

Love can end only in contentment and joy. Order is restored and love conquers all.

A finer staging of The Marriage of Figaro, combined with such a superb cast and orchestra I don’t expect to experience again in my lifetime.

A finer staging of The Marriage of Figaro, combined with such a superb cast and orchestra I don’t expect to experience again in my lifetime.

ALBERT EHRNROOTH

Seen at the Palais Garnier, November 30, 2025