The National Gallery, London

Is the AI revolution going to have as profound an effect on society as the Industrial Revolution had on the Midlands toward the end of the 18th century? Were people at that time as aware of a changing job market as we are today? Joseph Wright of Derby was there from the start, and he captured the scientific and industrial revolutions in action. His major paintings celebrate a new appetite for learning and perfectly embody the spirit of the Age of Reason.

Joseph Wright of Derby’s painting An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump undisputedly belongs in the British canon of art history, notwithstanding the fact that the work depicts a cruel scientific experiment. A Philosopher giving a lecture on the Orrery, Wright’s second most famous picture shows a natural philosopher demonstrating the workings of a mechanical model of the solar system.

Both paintings feature a central, magus-like figure who reveals the wonders of science to an audience of adults and children eager to learn. They also display Wright’s unparalleled ability – unequalled in Britain – to contrast light and dark in a room illuminated by a single candle. These two large canvases capture the scientific revolution in action while simultaneously celebrating a fresh appetite for discovery and knowledge. In this sense they perfectly embody the spirit of the Age of Reason.

The National Gallery restricts itself to the artist’s celebrated ‘candlelight’ paintings in its small but fascinating exhibition Wright of Derby From the Shadows. Although Wright was much admired for his ‘night pieces’, he also became an accomplished landscape artist and a gifted portraitist. The National Gallery owns his stylish and genial Portrait of Mr and Mrs Thomas Coltman, but it’s not included in this single-room exhibition.

Joseph Wright ((1734 – 1797) was born and raised in Derby. He trained in London with the portrait painter Thomas Hudson, who had also taught Joshua Reynolds. In Britain, there was no shortage of highly talented portrait artists and Wright would have known that he would have struggled to rival the likes of Gainsborough, Reynolds and Romney in Bath and London. But in Liverpool and the Midlands he did, according to his account book, become a successful portrait artist. Landscape painting was another option, but it had less prestige in the hierarchy of genres (dictated by the French) and was therefore less financially rewarding than history or portrait painting. Most artists aspired to concentrate on history painting, which was considered to be the most intellectually challenging and exciting genre.

Christine Riding, Director of Collections and Research at the National Gallery is one of the curators of Wright of Derby From the Shadows. She explains that Wright must have realised early on in his career that, to survive, he needed to develop his own distinctive style in the highly competitive London art market:

The first public sales exhibition of contemporary art was held at the Strand in London in 1760. Previously, paintings had been sold privately. For a shilling the general public could now visit an art exhibition, look around, and even purchase some of the paintings on display. This development opened up a whole new market for artists. They could take greater risks, hoping that this new audience would engage with and invest in innovative ideas.

Christine Riding says that Wright set out to create art that possessed the grandeur of religious and mythological painting while remaining rooted in everyday life. At the same time he wanted it to be awe-inspiring.

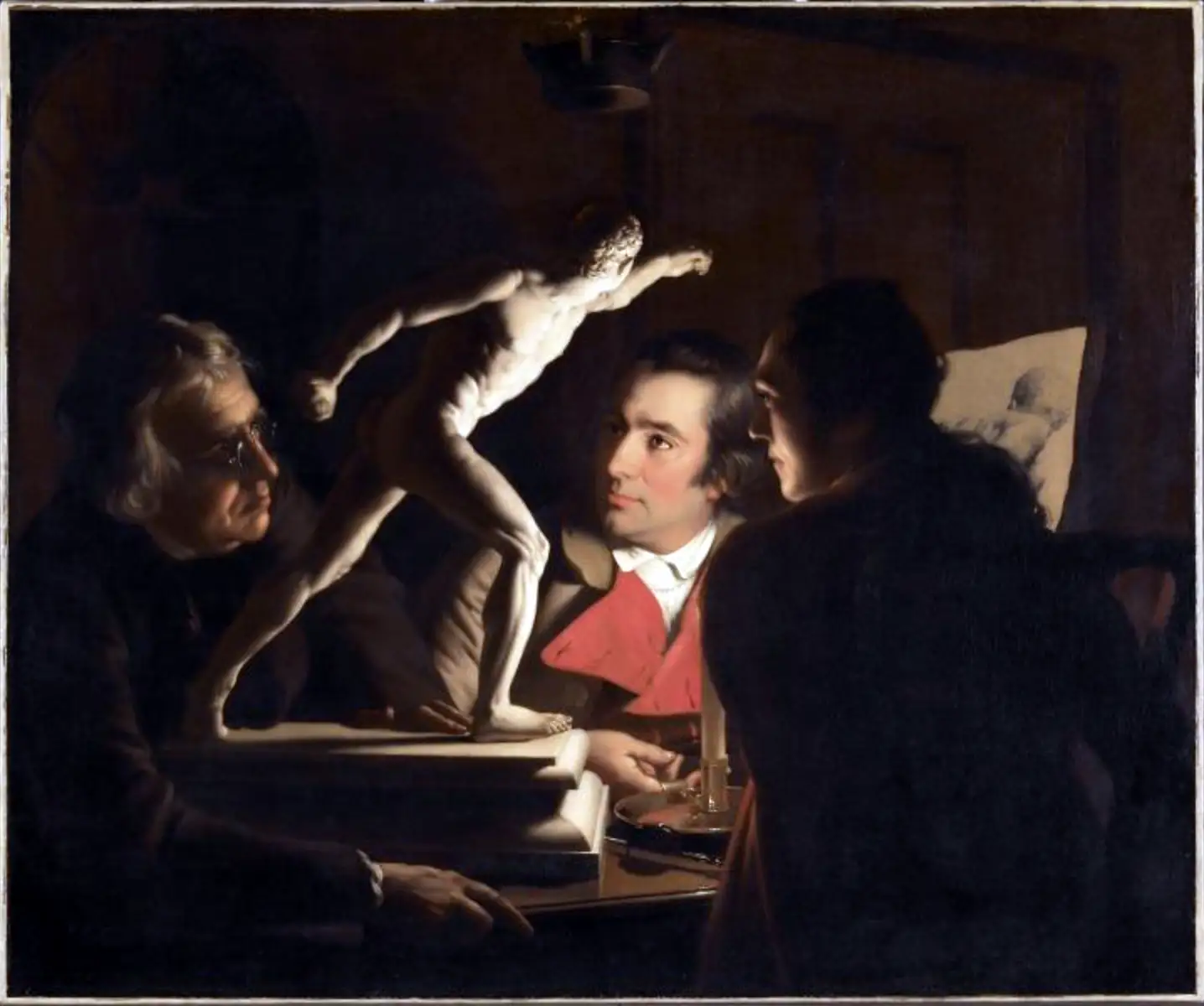

Wright made his London debut at the Society of Artists in 1765 with two works; Three Persons Viewing the Gladiator by Candlelight and a portrait that remains unidentified.

The Gladiator is one of Wright’s earliest candlight paintings and it is included in the exhibition on loan from a private collection.

In this work, three men are shown scrutinising a small reproduction of the famous Borghese Gladiator. In the background, part of a seventeenth-century print of the statue is visible. Two of the figures remain in the shadows, their faces only partially illuminated. The concealed candle casts a soft and warm light on the face of Peter Perez Burdett, a friend of Wright, who is depicted in striking detail. The elderly gentleman wearing spectacles has been identified as a resident of an alms house who, judging by the expressions of the younger men, acts here as the scholar in this study circle. The warm glow and calm that emanate from the scene are only surface qualities. On a deeper level, the painting explores the act of looking and reflects the influence of the philosopher John Locke, whose empiricist view held that all our knowledge of the world can only come from our experience – from learning through observation and experiment.

Wright ‘s use of chiaroscuro and tenebrism – the sharp contrast of light and dark to achieve a sense of space and volume– was uncommon in Britain at the time. Where could he have learned this technique? Caravaggio is credited with – if not inventing, then at least – being the first to apply chiaroscuro to powerful dramatic effect in his religious canvases. However Wright would not have seen any of Caravaggio’s work before undertaking his Grand Tour to Italy in 1773, a journey intended to broaden his artistic outlook.

While studying in London he could have come across works by French, Spanish and Dutch ‘Caravaggisti’ – followers of the Italian Baroque master. Dutch painters who excelled at depicting sparsely illuminated genre scenes were particularly popular among the British aristocracy. Wright could have seen works by Gerard van Honthorst and Hendrick ter Brugghen. But it seems quite likely that he saw paintings by Godfried Schalcken – a ‘fijnschilder’ known for his highly finished, atmospheric candlelit scenes – who for a few years painted at the court of King William III

We know from an unpublished memoir by Joseph Wright’s niece that, as a child, he was mesmerised by various methods of creating optical illusions – particularly the popular laterna magica (magic lantern) performances that used candles or oil lamps made it possible to project handpainted slides onto a wall.

After completing his studies with Thomas Hudson in London Wright moved back to his hometown Derby. There, and in Birmingham he socialised with prominent intellectuals such as the philosopher Erasmus Darwin (Charles’ grandfather), the potter Josiah Wedgwood, toy-maker Matthew Boulton and the steam engine inventor James Watt. The Midlands kick-started the Industrial Revolution and the Lunar Society in Birmingham provided the intellectual energy that fueled the British Enlightenment. It would later become the cradle of British romanticism.

Derby , as Christine Riding explains, turned out to be exactly the right place for what Joseph Wright set out to paint.

Connoisseurs, collectors and patrons admired Wright’s Three Persons Viewing the Gladiator by Candlelight , precisely because he decided to pursue this distinctive candlelit style. The title of his next great masterpiece is self explanatory: A Philosopher Giving That Lecture on the Orrery in Which a Lamp is Put in the Place of the Sun (1766). An orrery is a mechanical model of the solar system, and the National Gallery has managed to get hold of a working original device, exhibited alongside the painting.

The viewer’s eye is immediately drawn to the two innocent-looking children brightly lit by the hidden oil lamp. The youngsters are the only figures touching the mechanical model, which further supports the idea that Wright was inspired by John Locke’s tabula rasa theory – the notion that we are a blank slate at birth and are shaped entirely through sensory experiences such as touching, observing and reflecting. Three older boys, spellbound by the spectacle, emerge from the shadows into the light – a visual metaphor for enlightenment – while a young adult fixes his gaze on the scholar.

There is good reason to believe that the philosopher, cloaked in red, was modeled on a portrait of Sir Isaac Newton painted 75 years earlier. The wise man with long grey hair is appears slightly impatient with the figure beside him, who takes notes attentively. This ‘learner’ has been identified as Peter Perez Burdett , who also posed for Wright in The Gladiator. The surrounding darkness represents ignorance, yet in the dimly lit background a curtain is drawn back to reveal a shelf filled with books, the source of knowledge.

During Wright’s lifetime traveling natural philosophers (what we now call scientists) gave popular demonstrations for a ticket-buying audience in town halls and private homes, much like the scene depicted here.

Wright was never content to simply repeat himself. After the success of his more ‘serious’ genre paintings, he increasingly turned to creating so–called candlelight ‘fancies’ – whimsical compositions often featuring children engaged in playful or mischievous activities, such as Two Girls Dressing a Kitten or Two Boys Fighting over a Bladder. In these scenes, children are allowed to be children, no longer portrayed as miniature adults. Yet, the moral message associated with some of these works sometimes becomes obscured by the cute and saccharine image, painted with extreme attention to detail.

But Wright never confined himself to a single genre, even when it proved commercially profitable. While he was producing his charming candlelit ‘fancies‘ , he was also busy capturing the spirit of the burgeoning Industrial Revolution. An Iron Forge Viewed from Without was sold to Catherine the Great and now resides in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. It has not traveled to London, but its thematic counterpart A Blacksmith’s Shop is in many ways the superior painting. In it two labourers look hot and weary – after all, they’re working into the night – while their young families wait patiently in the shadows for them to finish. Until this point, scenes of toiling labourers had not been popular subjects in British art, yet Wright’s various versions of blacksmith paintings were much admired and fetched high prices.

To gain greater public exposure and reach a wider audience Wright commissioned several notable mezzotint engravers to produce prints after his candlelit paintings. The strong tonal contrasts in these works – his complete mastery of chiaroscuro – made them particularly well suited to mezzotint, a subtractive process which involves smoothing or lightening areas of a darkened plate using a scraper and a burnisher. The technique allows for subtle gradations from rich blacks to a range of greys and velvety mid- tones.

In some cases the mezzotint is even more compelling than the original painting. This is certainly true for Miss Kitty Dressing, the engraving made after the rather twee painting Two Girls Dressing a Kitten by Candlelight.

Wright’s absolute masterpiece, An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768), is in the same vein of thought as A Philosopher Giving That Lecture on the Orrery, but both philosophically and dramatically more accomplished.

Once more Wright only uses a single light source, hidden behind a glass vessel containing a blackened cranium– a symbol of mortality. The central figure in the red robe, who engages the viewer directly, looks more like an entertainer than a lecturer. He is performing a cruel and sadistic ‘scientific ‘ trick. One of the girls in the spotlight cover her eyes, while the younger girl clings to her, horrified by the potential outcome. Of the experiment.

The ‘magician’ has trapped a cockatiel in a glass vessel. The bird panics as it is slowly deprived of oxygen while the air is pumped out. Interestingly the instrument itself remains largely in the shadow. Wright seems less interested in the mechanics of the science than in the spectators’ reactions – some of whom appear more fascinated than appalled by the spectacle.

Then there are the two partially lit young lovers beside the lecturer, who seem to notice only each other. Love is stronger than death, seems to be the message. The pair is probably based on Thomas Coltman and Mary Barlow, whom Wright later portrayed in the double portrait Mr and Mrs Thomas Coltman (See image above).

Wright cleverly builds dramatic tension into the scene by withholding the outcome of the experiment. Is the lecturer – playing God – going to pump all the air out of the vessel, creating a vacuum and thus an ex-parrot? Or will he let the air back in and – god-like – allow the bird to be resurrected? That is the question that will forever remain unanswered. In this way Wright turns the whole experiment into an awe-inspiring and quasi-religious event. The painting is difficult to classify and once again Wright invents a new genre that lies somewhere between scientific demonstration and religious painting.

By the mid-1770s Wright had moved on from his candlelight phase – perhaps because these works were no longer selling as well. He took up portrait painting in Liverpool for a time and in 1773 set off for Italy. After two years he returned, continuing to find inspiration in the views that he had encountered on his travels. His landscapes are often melancholic, exploring nature’s breathtaking beauty, while occasionally hinting at industrial progress. In this way, he bridges the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution and Romanticism.

Joseph Wright of Derby is without doubt one of the quintessential artists of the 18th century Enlightenment and, on the evidence presented in this small exhibition, fully deserves his place in the British cultural Pantheon.

Christine Riding, finally, on the uniqueness of Joseph Wright of Derby’s works in Britain at the time.

Wright of Derby: From the Shadows

The National Gallery, London: 7 November 2025–10 May 2026

Derby Museum and Art Gallery: 12 June–1 November 2026