Tate Modern’s presentation of Emily Kam Kngwarray’s batiks and acrylic paintings – 29 years after her death – is the first large-scale exhibition of her work by a major European art museum. Kngwarray is now recognised as one of the most influential and significant Australian artists of the 20th century and the country’s most expensive woman artist.

Kngwarray’s somewhat belated international acclaim is not surprising: she began painting on canvas in her late seventies and her career only lasted eight years. Her incredible prolificacy produced more than 3.000 works, proving that age was no barrier to artistic greatness.

Do you need knowledge about indigenous art to appreciate Kngwarray’s work?

Not necessarily. It’s possible to enjoy the paintings as a form of abstract art consisting of brilliant colours, enigmatic symbols, swirling lines and thousands of dots. But understanding her cultural background and spiritual grounding enriches the experience. This is art deeply rooted in (Australian desert) Country, its ceremonies, ancestral stories and songs.

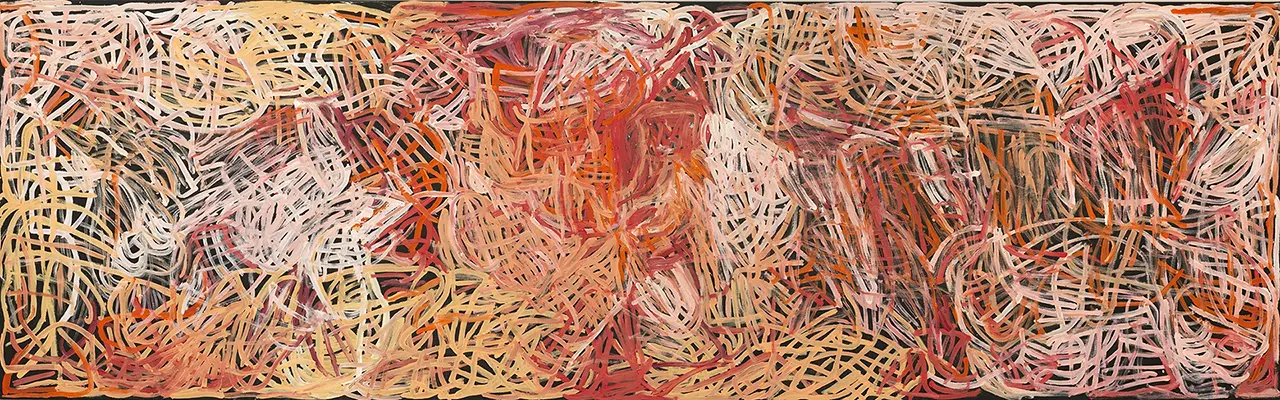

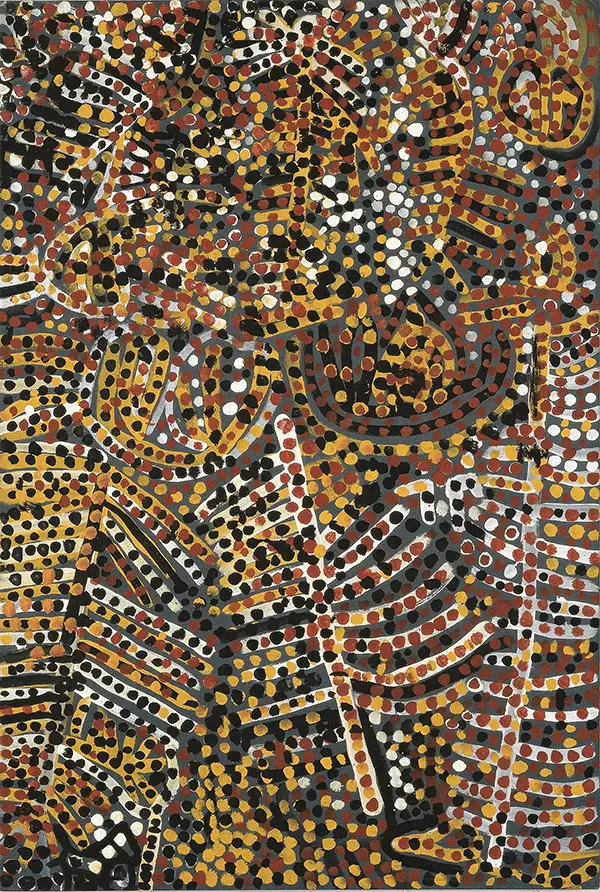

All of Kngwarray’s imagery can be traced back to her ancestral home in Alhalker, in the Sandover region of the Australian Central Desert. She is perhaps best known for her vibrant, bright coloured dot paintings with overlaying dots, obscuring the symbols of her Dreamings *. In the final years of her life, however, her style shifted radically: the stippled patterns gave way to bold, fluid horizontal or vertical parallel lines in earthy tones, that echoed Anmatyerr women’s body painting. These later works became increasingly dense and entangled – evoking the subterranean roots of the tuberous anwerlarr yam, the plant with which she shared her name.

Kngwarray wasn’t keen on explaining her work, but she was clear about its source: the spirit, animals and plants of her country: ¨I paint my plant, the one I am named after – those seeds I am named after. Kam is its name. I am named after the anwerlarr plant. I am Kam!…. I keep on painting the place that belongs to me – I never change from painting that place. ¨

She saw herself as inseparable from the natural world (Country) she grew up in. She didn’t have any children of her own, but assumed kinship responsibilities within her community and regarded Country and Dreamings as part of her extended family.

Paintings from the latter part of her career have been seen as non-figurative art and she has been compared to Western modernists. Yet Kngwarray’s exposure to Western art before she began painting would have been minimal. What she probably did know, however, was the Papunya Tula movement – an indigenous art collective that almost certainly influenced her style. Papunya lies about 240 km northwest of Alice Springs, while her own country, Alhalker is 230 km northeast of the Northern Territory town.

The Western Desert painting movement originated in Papunya in the 1970s. At first, only men were allowed to paint, and they became the first Aboriginal artists to use synthetic paints on canvas. Early works sometimes revealed sacred knowledge restricted to initiated men. By the late 1970s the movement had gained popularity and their artworks began to sell in the big cities, which meant that artists could no longer feature secret symbols.

In 1978 the Women’s Batik Group was established, with the help of government money, in Utopia, near Kngwarray’s birthplace in Alhalker. She joined 80 women in workshops that taught wax-resist dyeing and other techniques needed for batik-making, and over the next eleven years she produced hundreds of batik designs.

Tate Modern presents eleven of her batiks on silk and cotton, hung from ceiling to floor.

Many are untitled, yet most depict recognisable animals (Emu dreaming, 1988), plants (Kam, 1988) and seeds – motifs connected with her ancestral lands. The centrepiece is the spectacular, almost sculptural ten metre long silk batik – folded in half – that takes up a central place in the last exhibition room. The yellow and red, intricately worked organic forms and symbols inundate the space with spirituality. It’s like a totem in silk. But by the time she was in her late seventies she found batik making too tiring and she switched to painting on canvas, simply because ¨it was easier¨.

She had always painted seated, the batik draped across her lap. This working method shaped her free-flowing, nonlinear style. When she turned to painting she ignored the easel, laying the canvas flat on the ground in front of her.

Her early paintings drew on the same deep-rooted oral and traditional motifs present in her batik work. Parallel lines with outward-facing barbs symbolise kangaroo tracks, while emu prints are represented by arrowlike motifs. The meandering paths between waterholes became even more pronounced. These works offer a kind of aerial view of the artist’s Country, without resembling Western maps. Instead, they form pathways into Anmatyerr culture – Kngwarray’s culture.

Kngwarray’s early paintings already featured dots, but over time they became denser and more intense in colour. The technique recalls traditional sand drawing, where fingertips press circular indentations into sand.

acrylic paint on canvas, 213 × 120

Dots overlay Dreamings, animal tracks, and even other dots. Their colours reflect seasonal shifts – reds, yellows, greens and purples evoking the bush flowers in bloom. This is a kind of pure pointillism, unconnected to scientific colour theory. Buried beneath the stipples lies – we are told – the Dreaming narrative of the yam story, for which Kngwarray was custodian. In these large paintings the seedbearing flower Kam and other bush flowers appear on the surface, the colours reflecting the seasonal changes.

In the latter stages of her career, Kngwarray’s style shifted once more: dots began to dissolve, giving way to fluid colour planes and tentacle-like forms that swirl enticingly. My Country (1993) and Mern Everything IV: Bush Food (1993) exemplify this evolving technique.

Her pièce de résistance is the monumental Alhalker Suite (1993), a cycle of 22 canvases that seem to offer either an aerial view or a celebration of long-awaited rain in Alhalker Country after long periods of drought. It’s a jubilant bush symphony, but the tones are surprisingly muted, with purples, pinks, greens, and all kind of blues dominating the surface.

In the final two years Kngwarray abandoned the stippled and blossom patterns, instead developing a rather austere linear style, directly echoing the striped designs used when ‘painting up’ for awely – the women’s ceremonies in Anmatyerre Country.

As mentioned earlier, the final paintings with intricately layered, intersecting lines – most powerful in a monochorme palette– trace the edible root system of the yam plant. In the end Kngwarray embarked on painting the writhed subterranean root system of her Dreaming. She returned to gestural painting that in the most direct way expressed her cultural identity, spiritual belief and connection to Country. It echoed the sinuous patterns that have been drawn in the sand since time immemorial, creations of the past that remain eternal.

* The Dreaming is a traditional term used in Central Desert languages to describe the legal, spiritual and cultural ‘laws’- closely related to the landscape. These laws refer to the ancestral creation period when spiritual beings shaped the land, its topography, animals and people. This is celebrated in ceremonies with stories and songs that animate how the land and sacred sites were shaped. They govern relationships between people , the land and all the living creatures around them. Individuals or groups may have the responsibility (or act as custodians) for particular Dreamings. Being a custodian means that you’re trusted with the care of sacred sites, practice ceremonies, and pass on knowledge and stories about a specific plant, animal, sacred site or landscape.

Emily Kam Kngwarray is at Tate Modern until 11 January 2026

You can find more information about the exhibition here

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.