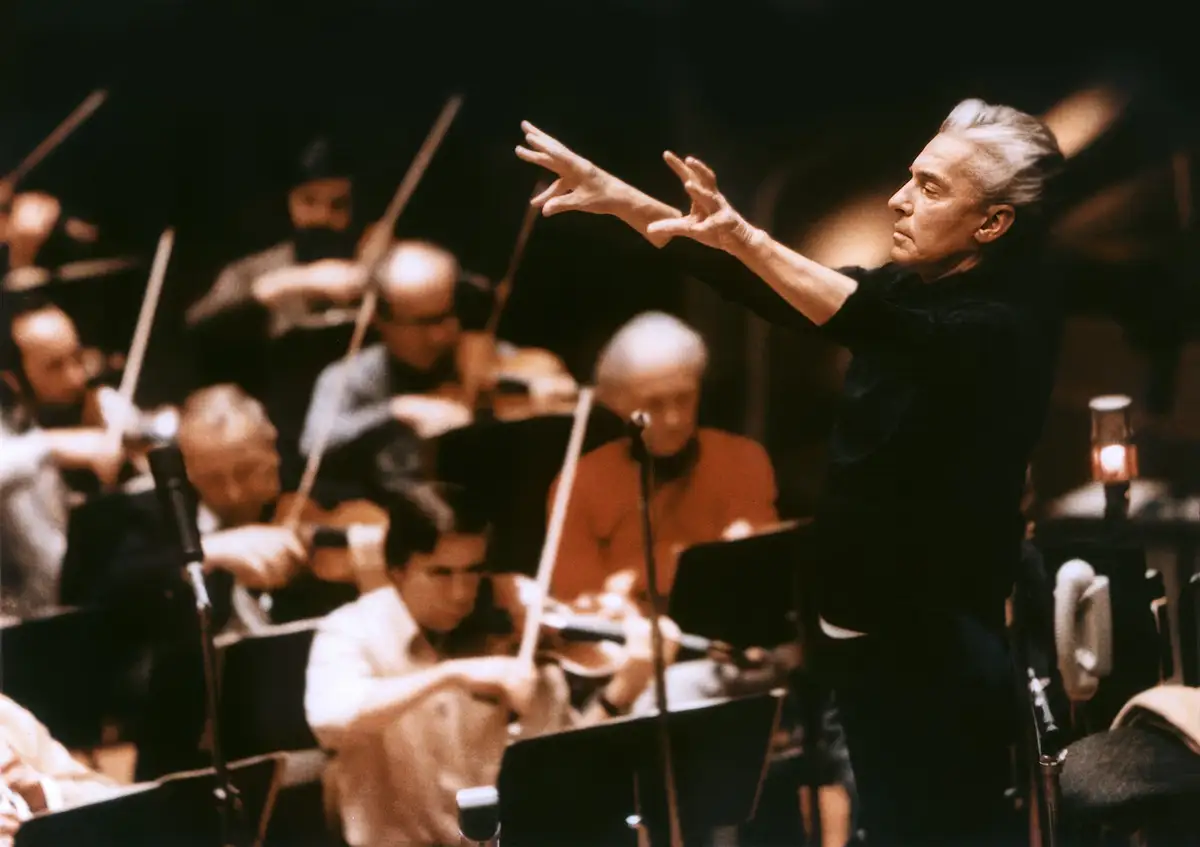

Herbert von Karajan had a habit of conducting concerts with his eyes closed. He knew he could trust his players to follow him blindly. For some players this was a slightly unsettling experience, yet the concerts offered an incredible sense of freedom once the often lengthy and difficult rehearsal process was over.

In rehearsals Karajan would maintain direct eye contact with the musicians, but he made a point of not talking too much, rarely explaining in detail what he wanted. Instead, he expected the musicians – in this case the Berlin Philharmonic – to read his intentions mentally, through his gestures. This unspoken language was one reason he worked with a fairly limited number of orchestras, all of them familiar with his style of conducting. Rehearsals were intense, and at times he would resort to shouting, but he always knew what he wanted. Some phrases, or even just a note, might be repeated endlessly until it achieved exactly the timbre or intensity he had in mind.

By the 1950s Karajan had earned the nickname General Music Director of Europe as he was commuting between his regular gigs in Berlin, Milan, Salzburg and London. His absolute authority – not only over all things musical, but also over recording, filming and promotion – belongs to a different era. Even during his lifetime, Karajan was often portrayed as self-obsessed, egoistical, cold and rather unpleasant. Yet his concerts were rarely reflecting those unflattering characteristics. He placed himself in the service of the music, albeit not without leaving his unmistakeable personal stamp on it.

Last year, the Berliner Philharmoniker released an extensive box set on their own label featuring radio recordings made with Karajan between 1953 and 1969. The latest edition covers the 1970s which, according to many of those who attended the concerts at the Philharmonie or heard the radio broadcasts, represented the orchestra’s finest period under his leadership.

This latest box set treats the listener to 20 concerts on 20 CDs, recorded for Sender Freies Berlin and Radio in the American Sector. Most of the material has never been released before. It’s only fair to note that several compositions appear in both box sets, albeit in new versions. They are not always improvements, nor are they necessarily very different from the older recordings, but they do offer an opportunity to trace Karajan’s and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra’s (BPO) development over the two decades the orchestra firmly established their reputation as one of the world’s outstanding ensembles.

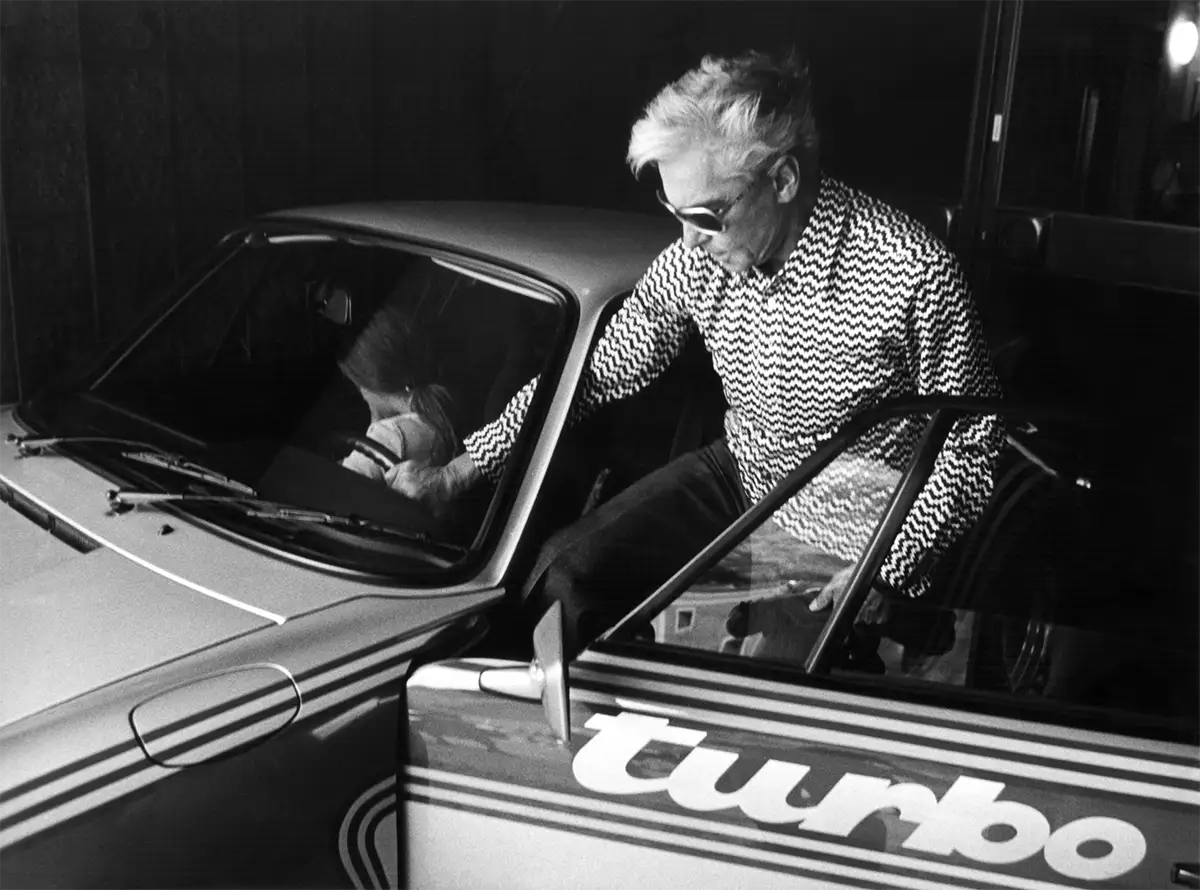

In the 1970s Karajan was extraordinarily active, with many irons in the fire. For Deutsche Grammophon he made very successful recordings, amounting to more than 80 CDs in the 1970s. He had founded the Salzburg Easter festival in 1967 and added Salzburg Whitsun Festival to his roster in 1973. He also established the Karajan Conducting Competition in 1969 and, in 1972, the Orchestra Academy of the Berlin Philharmonic to train young musicians. At the same time, he revolutionised the filming of classical concerts, planning every detail meticulously. Paradoxically for these ‘concert films’ he often required the BPO to simply play along – in fact just mime – to a pre-recorded playback track. On top of all this, he always conducted concerts (though never rehearsals) without a score, a practice that demanded extensive memorisation.

Karajan made his debut with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1938, the same year he first conducted Bruckner’s Fourth Symphony to great acclaim. He recorded all of Bruckner’s nine symphonies with the orchestra between 1975 and 1981. The radio recording in this box was made in parallel with the 1975 studio recording.

The opening pppp string tremolando has a whispering quality that makes the wistful horn entry especially seductive. From the outset there is a greater sense of urgency than in Karajan’s 1970 recording – the first movement is two minutes faster – and the sound is drier yet richer. Overall, the radio recording is about six minutes shorter. It corresponds time wise, and in many interpretative ways, with the 1975 recording for DG.

The second subject, which Bruckner referred to as the Gesangsperiode, and the third thematic group were inspired by the song of the great tit (yes, that’s a bird). The BPO strings lend this passage a magic and grace that this fairly common garden bird doesn’t really possess. The Andante starts off in a mournful mode, livens up, before drooping down to brief silence. The restart is a drowsy drip with plucked strings, but towards the close of the movement the future looks pretty good again, and the repeated opening phrase now sounds cautiously optimistic. The Scherzo, launched by horn fanfares, has plenty of vim and jolly-huntsmen swagger. In the following Trio – during the huntsmen’s lunch break – the mood is laid back and we are treated to a rather slow Austrian Ländler. It could be a bit more danceable. The Finale is problematic and structurally weak, through no fault of Karajan. Conductor and orchestra nevertheless manage to find some sort of logic in the monolithic unison blocks and key uncertainties that are put in front of them. Bruckner revisits themes from the previous movements, turns ominous, attempts some contemplative nature painting, and invites us to a Volksfest (as instructed in Bruckner’s autograph score), before the Romantic symphony closes in a blaze of glory, and we return to the beginning. It’s clear that we are here on Karajan’s and the BPO’s home territory. It’s hard to beat this interpretation.

Two recordings of Bruckner’s Fifth Symphony are included in the box. The later one was made one day after the 1976 studio recording, and once again it represents an improvement. The Adagio opens with alluring dissonances – pizzicati on double basses, followed by a chorale-like string passage – reminiscent of Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater and the Recordare from Mozart’s Requiem. The phrase returns in the exposition, but is repeatedly interrupted by brass fanfare and orchestral unison. This pattern can get tiresome and therefore requires precision, rigidity and a sense of overarching coherence – qualities Karajan displays throughout the symphony. What is sown in the opening movement, is reaped in the Finale: the inner and the outer movement share both key and thematic material. They also have in common that Bruckner incorporates complicated and often surprising contrapuntal writing (including three fugues in the Finale). Among Bruckner’s secular works the Fifth is arguably the most overtly Christian, its spiritual and metaphysical character closely aligned with Karajan’s own beliefs. That affinity is palpable in this performance, which ranks among the highlights of the box set.

The booklet contains three highly informative essays by Tobias Möller, Richard Osborne (author of a biography about Karajan) and Peter Uehling. All three writers are refreshingly outspoken about the strengths and weaknesses of Karajan’s style. Uehling, in particular, also offers his own, very honest, assessments of many of the concerts included in the package.

Karajan began rebuilding the BPO following Furtwängler’s death and his own appointment as chief conductor in 1956. He aimed to create a dream team of younger, virtuoso players who would help shape what became known as the technically polished ¨Karajan sound¨ : legato-driven, lush brass; liquid-toned woodwinds; and vibrato-rich, silky strings.

Peter Uehling ensures that the names of several oustanding wind players who joined the ranks are not forgotten. As he writes: ¨They included the flautist Karlheinz Zoeller, the oboist Lothar Koch, the clarinettist Karl Leister, and the horn player Gerd Seifert. Although each of them had his own individual attitude to questions of sonority, they harmonized extremely well. And thanks to the work of concert masters such as Michel Schwalbé, Leon Spierer, and Thomas Brandis the orchestra developed a string sound which, its radiance notwithstanding, remained light enough not to cover the de- tailed sounds in the winds¨

The concertmasters Thomas Brandis (vl) and Thomas Borwitzky (c) are the soloists in the Brahms Concerto for Violin, Cello and Orchestra. It is sometimes called the ‘reconciliation concert,’ as Brahms dedicated it to the violinist Joseph Joachim, after the two had fallen out over Joachim’s divorce. The gesture worked: the violinist gave the world premiere, with Brahms conducting.

It is therefore somewhat curious that the cello is given the lion’s share of the meaty solos. The opening movement begins with a resolute statement: the first subject is presented by the full orchestra in four bars before the cello alone carries it forward. The clarinet then introduces the second subject, which is taken up by the violin The following double cadenza offers a taste of the virtuosity to come and quickly establishes Brandis and Borwitzky as a well-matched partnership. The orchestra gives the main theme a full exposition before it is again left to the cello, echoed by the violin to introduce the second theme.

The Andante is bathed in rhapsodic warmth, and melancholic lyricism. Borwitzky and Brandis make liberal use of vibrato, but it doesn’t bother me as it never feels excessive and their vibratos are perfectly matched. Karajan remains discreetly in the background, allowing the soloists to shape the movement’s lyrical lines. In the Finale, a Rondo, orchestra and soloists engage in a more animated dialogue. Brahms’ Hungarian dances had already enjoyed great success and while composing the Double Concerto he was also working on the Zigeunerlieder, Op.103. The gypsy inflection is unmistakeable in the Finale, which rolls merrily along without being overly exuberant. Using two members of the orchestra as soloists works a treat in this context; Brandis and Borowitzky sound fully integrated and consistenly supported by their colleagues. They may not project the individuality of famous pairings like Heifetz and Piatigorsky or Oistrakh and Rostropovich, but their performance is compelling enough to prompt the question of why this concerto is heard so rarely in the concert hall.

Karajan conducted the works of Beethoven and Brahms less frequently in the 1970s. Peter Uehling remarked that the BPO and their chief conductor could play all the Beethoven and Brahms symphonies in their sleep. In Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, recorded in 1978, that familiarity shows: the performance sounds fatigued and several rhythmic passages are poorly articulated, lapsing into formlessness.

Brahms Second Symphony, performed on the same programme as the Double Concerto tells a different story. Not a trace of formlessness or routine. There’s lyrical breath and a lullaby in the first movement, followed by ¨black wings¨and despair in the second movement, tinged with a gentle Schubertian quality. The Slavonic dance-like, country-waltz third movement exudes rustic charm. In the Finale, bursts of unrestrained joy and optimism banish the dark shadows and gloom that underlie the earlier movements. Here, once more, Karajan and the BPO are at their expansive best, never losing sight of Brahms’s rigorous sense of form.

It’s well documented that Karajan was tone-deaf to most contemporary music and its noisiest representatives. However, the box set does include three distinctly modernist works. Werner Thärichen’s Batrachomyomachia, a piece for two solo percussionists, orchestra, a baritone soloist and a chorus, is also known as The Timpani War. The title is borrowed from a Greek parody by an unknown author of the Iliad, which translates as Battle of the Frogs and Mice. For 36 years, Thärichen was the BPO’s solo timpanist while also being a prolific composer. The singing is done in mock Greek, interrupted by loud drumming, blaring brass and various other effects; however, the humour wears thin over its 37 minute duration, becoming rather tedious long before a battle ensues in which the mice emerge victorious. Small wonder, then, that this is the work’s sole recorded legacy.

A far superior offering, Gerhard Winberger’s Plays for 12 Solo Cellos, Wind and Percussion showcases the hand of a proper composer-conductor. While flirting with serialism, Wimberger ensures the texture remains listener-friendly, imbued with a certain nostalgic warmth. The cello soloists are fully independent and frequently subdivided into smaller groupings. The percussionists are tasked with dislocating and initiating rhythmic patterns. The BPO’s cellos, winds and percussion manage to maintain the clarity within dense, post-tonal textures. The Swings movement opens with a motif that resembles the iconic Bond theme, and it’s the most convincing of the four movements.

For whatever reason Karajan chose Krzysztof Penderecki’s Capriccio for Violin and Orchestra, it is the most satisfying performance of the modernist pieces. The caprice features some unusual instrumentation : electric bass guitar, musical saw and four saxophones, besides the regular instruments. The BPO’s concertmaster, Leon Spierer, plays the fiendishly difficult solo part. There are quite a few recordings of the Capriccio; I’ve done a comparison with at a performance from 1967 by Wanda Wilkomirska with the National Philharmonic Orchestra in Warsaw. Wilkomirska doesn’t hold back, but Karajan is better at creating eerie sonorities in the middle section. As one would expect, Karajan, the BPO and Spierer are more concerned with beautifying or smoothing out (blunting?) the sharper contours of the piece than their Polish colleagues. The quasi–improvisatory passages are handled more convincingly by the Poles. The piercing violin tones in the middle section is the stuff of horror movies – Penderecki provided the music for a number of them. A good illustration of the very different approaches are the waltz fragments that are dropped in towards the end of the Capriccio. The Poles make the triple time dance sound like an impatient driver using his vehicle horn, whereas Karajan turns it into a Bavarian Oom-pah-pah waltz.

After the war Sibelius’s symphonies were often viewed with disregard by critics and avant-garde circles in Germany. However, Hans Rosbaud, Karajan and later Kurt Sanderling in the 70s, continued to champion the Finnish composer’s works. Karajan made a number of fine recordings of the symphonies (though he never recorded No. 3) with the Philharmonia Orchestra in London and the BPO. Among the radio recordings is a performance of Symphony No.4. I’m not familiar with Karajan’s Sibelius recordings for EMI and DG, but I do know a great many recordings by Finnish and British conductors and orchestras.

Perhaps the highlight of this box set is Sibelius’s Violin Concerto.

The official Karajan.org website states: ¨The great French musician Christian Ferras was Karajan’s favourite violinist during the 1960s and early 1970s.¨ Ferras made his debut with the BPO as a teenager, playing the Beethoven violin concerto with Karl Böhm. He was consequently signed by Karajan to record the major violin repertoire. But Ferras struggled with depression and in 1967 the project was abandoned. He hit the bottle, cancelled engagements, and was dropped by record labels. However, in 1971 Ferras made one of his mini-comebacks. Judging by the Violin Concerto included here, he was playing as if his life was at stake.

At the start of the first movement, Allegro moderato, the soloist is instructed to play dolce ed espressivo. Many violinists take this to mean ¨glacially’ (or glacialmente, if such a term existed). Not Ferras: he is the epitome of expressive, from start to finish. His cadenzas are the stuff of blood and tears. He is effortless in the double, triple and quadruple stops and fearless towards the end of the first movement. In the Adagio the Philharmoniker are quietly supportive – comforting and restrained. Ferras’s vibrato may be old school, but his Stradivarius (he owned two) sounds all the more beautiful for it.

The Allegro Finale with its “long-short-short-long” rhythms reminiscent of a polonaise, was infamously described by the critic David Tovey as ¨a polonaise of polar bears.¨ Sibelius himself described the movement as a danse macabre.¨ Ferras dips briefly into the darkness of the movement, but doesn’t linger. There’s no time, Karajan keeps it moving. The virtuosity on display is ear-boggling (I made that word up). Listen to the flute-like notes at 5:11. The macabre polar bear dance is brought to a heavy close with the violin’s parallel octaves, coupled with the full force of the orchestra.

This is the most lyrical performance of the concerto that I’m familiar with. Perhaps not to everyone’s taste – but I love it.

In the 1980s Karajan’s controlling nature and his controversial Nazi past serously strained his relationship with the Berlin Philharmonic and the critics. His signature, highly polished sound fell out of fashion and the commercial success of his record releases was sometimes held against him. Following a stroke in 1978, his physical decline led to a more rigid conducting style, forcing him to rely on fewer arm gestures. Although his increasingly slow tempos drew criticism, he developed a more profound insight into the German-Austrian repertoire.

The Berliner Philharmoniker reached its pinnacle under Karajan, their conductor for life, during the first half of the 1970s, as demonstrated by the recordings in this collection.

I will endeavor to review a few more concerts, when I find the time, from this fascinating box set which is now available from all good Berlin Philharmonic shops, as well as online.

THE BERLINER PHILHARMONIKER AND HERBERT VON KARAJAN: 1970-1979 live in Berlin 20 Hybrid CD-SACD

You can find a detailed listing of all the concerts and how to buy the largely unreleased recordings HERE

I have previously reviewed Kirill Peterenko conducts Arnold Schoenberg with the Berlin Phil. There are some excellent interpretations in this 3 CD box set. Click here.