BBC Proms 3 September 2019 Beethoven Piano Concerto No.4, Bruckner Symphony No.7 Vienna Philharmonic, soloist: Emanuel Ax, conductor: Bernard Haitink

Last year it was announced that Bernard Haitink was going to take a sabbatical. A sabbatical at 90?

It turned out to be a false rumour. Haitink is simply retiring. One of this and last century’s top conductors is quitting.

Haitink initially claimed he was going to take a sabbatical because he wanted to avoid official farewell concerts. It reflects his naturally shy character. In June Haitink conducted his last concert at the Concertgebouw. But it was not the resident Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (RCO) that accompanied his last concert in the building where his career started. Haitink made his debut in 1956 with the Concertgebouworkest (without the royal prefix in those days) but became the chief conductor of the Radio Filharmonisch Orkest in 1957. It was with that orchestra he decided to play his final concert in the Netherlands, rather than the much more famous band ( RCO) where he was at the helm for 27 years!

The maestro has already said his goodbyes in Munich (with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra) and Chicago, where his tenure as chief conductor at the Chicago Symphony Orchestra is remembered fondly.There will be one more final concert this Friday 6 September in Lucerne where he will conduct the same programme that we were treated to in London.

Surely it is no fluke that this Prom was Haitink’s 90th. His first appearance at the Royal Albert Hall was in 1966 and that time Bruckner’s 7th symphony was on the bill, just like the other night. Surely not a deliberate choice as Haitink recently has been conducting that symphony everywhere he went.

So, why has he not said his goodbyes to the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra where he learnt his trade and helped to develop an elite orchestra with a an international reputation. Haitink has been hurt in the past. Perhaps at times a little bit too easily. But it must be said that the Concertgebouw Orchestra , that probably owe their Royal title to him, have at times treated him badly. In 1988 Haitink left Amsterdam because he felt no support or appreciation from the orchestra management. But it must be said that Haitink became an even better conductor after he left his home country. He had already been the artistic director at Glyndebourne when he became music director at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden (1987 – 2002). Despite some real triumphs, particularly with Wagner operas, he never saw himself as an opera conductor. “I am a conductor who conducts operas”, he said in one interview. “Antonio Pappano, that is a real opera person”. But he admits conducting opera enriched his music making. The Dutch didn’t have a dedicated opera house until the Stopera (Het Muziektheater) opened in Amsterdam in 1986. But Haitink was never invited to conduct there.

Haitink says that opera never used be part of the Dutch DNA and I think he is right (having grown up in Holland in the 70s and 80s). Things have changed and that is very much to Pierre Audi’s credit (he was artistic director of the Dutch National Opera until 2018).

If this was indeed Haitink’s last London concert, and he hasn’t ruled out that at short notice he could replace a colleague who has fallen ill, it was almost as good as you could have ever wished. It helps that the Vienna Phil in this kind of repertoire is virtually unbeatable.

Emanuel Ax replaced Murray Perahia and I don’t think you will today find a better interpreter of Beethoven’s fourth piano concerto (well, Perahia may be equally good). There was a slightly comical moment as the maestro and Ax entered ( to a roaring, roof-lifting applause). Ax helped Haitink up on the rostrum, but from my position, facing the stage at a slight angle, I could only see the back of his head. The rest of the conductor was hidden behind the gi-normous grand piano that had its lid up to the max. So, it was impossible to see what Haitink was up to during the Beethoven concerto. But Ax didn’t leave Haitink or the orchestra out of his sight, that much was clear. Ax was careful not to stamp too much ego on the performance and I can imagine that some people would criticise Ax for not breaking the mould at any point. The long cadenza at the end of the first movement was magnificent ( not sure who wrote it).

It is well known that Bruckner composed cathedrals. They were musically fairly simple and straightforward, and clearly constructed by an organist. He worked with blocks of sound and you can at times in the orchestration hear the contrasting registers and manuals of an organ in full flow . The long-breathed harmonic idiom takes a leaf out of Wagner’s book. Particularly in the seventh symphony the Austrian doesn’t seem to want to detach himself from his German idol. The symphony was dedicated to King Ludwig II, Wagner’s most important supporter. The Adagio was composed ” in memory of the highly blessed, profoundly revered, immortal master” (i.e. Wagner, who died in Venice during the composing process).

The first movement’s 22-bar main theme (cellos, horn and violas to start with), with its ascending fourths and fifths, is reminiscent of the prelude of Das Rheingold . In the Adagio we hear for the first time the four distinctive Wagner tubas (that can also be heard in (Das Rheingold) And yet, despite these almost-quotations the seventh symphony is without a doubt a masterpiece. It is full of hummable long lines and some clever contrapuntal treatment of the main theme. Bruckner certainly isn’t afraid of a repeat when he has found a good tune. Bruckner was deeply religious and it is claimed that you can hear it in his seventh. It is possible to stress that point, but Haitink has no truck with religion. The religious works were never Haitink’s forte. So, this interpretation was not a solemn, elegiac poem to the memory of Wagner (who died while Bruckner composed this symphony). Nor was it a played like Haitink’s symbolic Abschied to the concert stage. Haitink and the Vienna Phil actually gave a fairly straight, or rather ‘nuchter’ (that is sober with a Dutch tinge) performance. Yes, there was splendour and grief, but also a very forceful scherzo and if you closed your eyes you could have imagined the orchestra dancing its way through the finale.

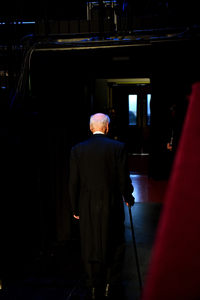

As always, at least during the past 4 or 5 decades, Haitink conducted with restraint. The right hand as firm as ever, mainly moving in front of the body. The left hand only occasionally indicating a change of dynamics, an articulation or encouragement to an individual. Haitink is also very good at picking out and signalling individual musicians with his eyes. But there are no superfluous hand gestures, the music flows out of his arms , musicians seem to read his intentions instinctively. Niks, geen kapsones, as they say in Dutch (no haughtiness or vanity) . After 65 years at the helm, Haitink surely is every musician’s dream conductor. And now he is almost gone (but not dead!!), leaving a huge musical space that eventually will be filled with conductors that hopefully have studied this absolute maestro in action.

Photo:Chris Christodoulou