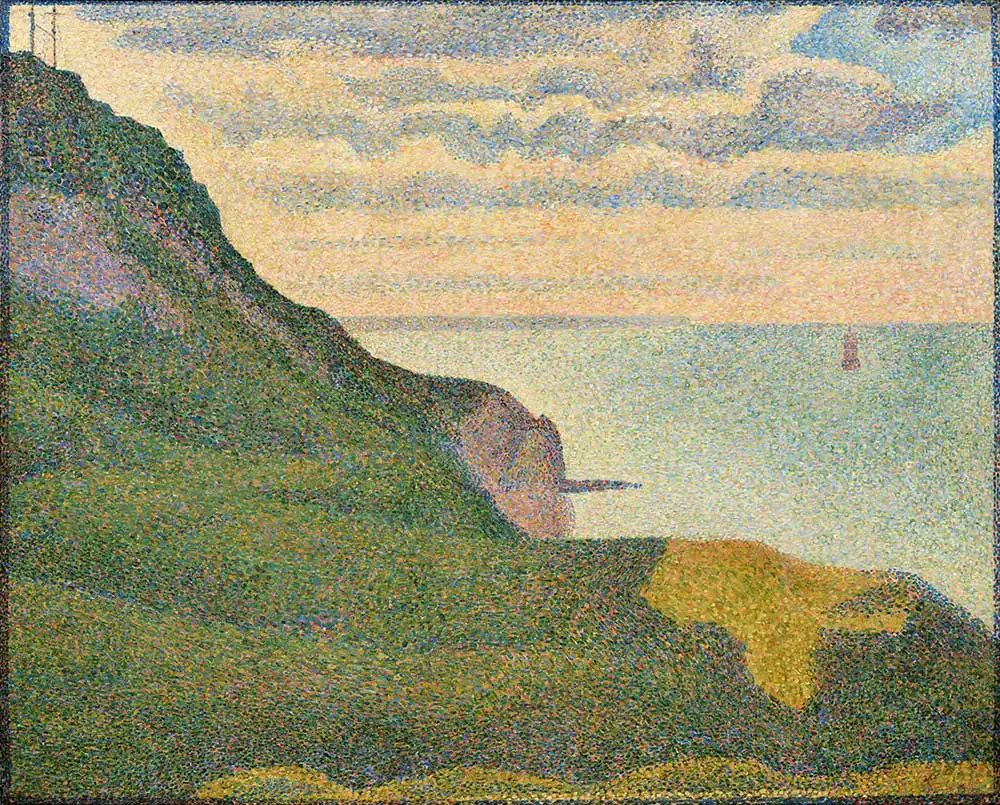

In his short life, Georges Seurat (1859 – 1891) finished approximately 45 oil canvases. Just over half of these were created during his visits to the Channel coast. Seurat’s seascapes, however, seldom receive the attention they deserve when displayed alongside his better-known, much larger paintings A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, Bathing, Asnières, Le Cirque and La Chahut. These popular works show Parisians enjoying the outdoors, the circus and can-can dancers. While these renowned works depict Parisians enjoying all kinds of leisure activities, the ‘marines’ – depicting harbour and sea views – are almost completely devoid of people. Is there an explanation for this disparity?

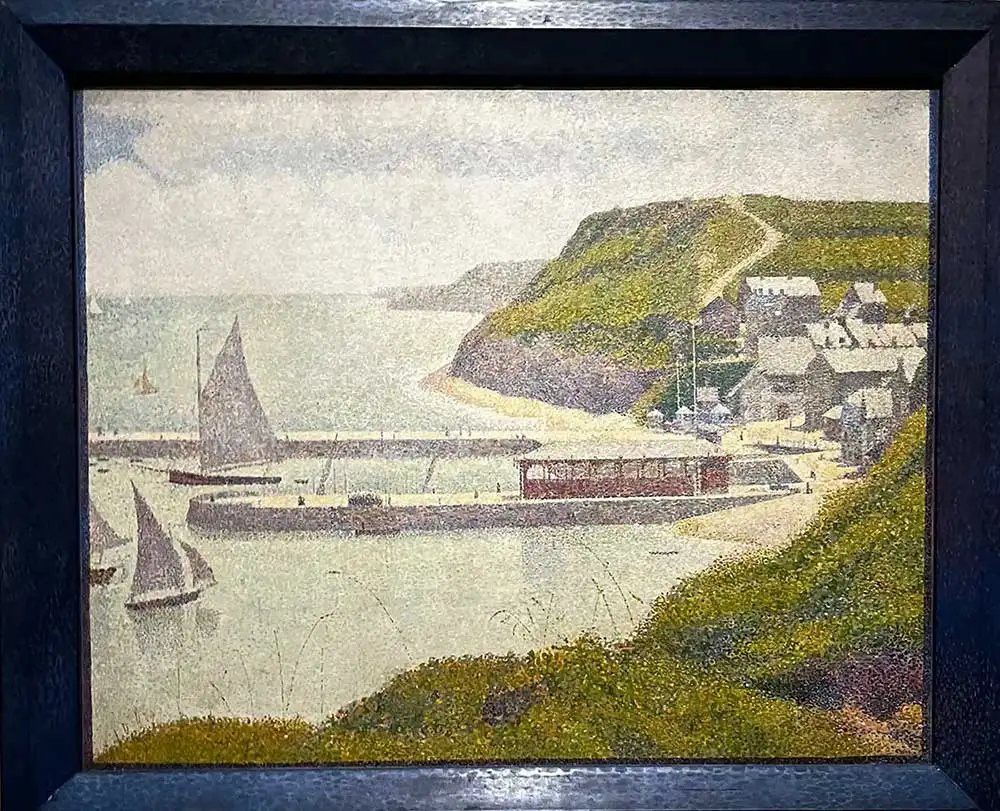

The last major retrospective of Georges Seurat’s work took place in Paris and New York in 1991-92. Since then there have only been a number of minor exhibitions, but the Courtauld Gallery ‘s Seurat and the Sea is the first show to focus solely on the artist’s yearly visits to the northern coast of France. The Courtauld has assembled seventeen of Seurat’s twenty-four canvases featuring sea and port motifs created between 1885 and 1890. In addition, this relatively small but impressive exhibition includes nine oil sketches and Conté crayon drawings, offering a fascinating insight into Seurat’s meticulous preparatory process.

During his lifetime the seascapes, with their melancholy and contemplative character, attracted considerable attention, particularly within artistic circles. In an essay Robert Delaunay even described thim as ¨the first theoretician of light. It’s high time these works are valued and recognised as the pioneering achievements they truly are.

Georges Seurat will forever be remembered for introducing a revolutionary painting technique that was termed Pointillism or Neo-Impressionism – a label he himself disliked. He preferred instead to describe his innovation as Divisionism or Chromoluminarism.

Georges Seurat enjoyed a comfortable bourgeois upbringing, only briefly disrupted by the Paris Commune in 1871. His family was well of and, like Degas and Cézanne, he had no financial worries. In fact, only three of his paintings are known to have been sold during his lifetime. His eccentric father spent much of his time away from the family at a cottage on the outskirts of Paris, where Georges would occasionally join him to paint.

At fifteen he enrolled himself at a municipal art school where he was instructed in copying engravings and classical sculpture. At seventeen, he was accepted at the École des Beaux-Arts, a stronghold of conservative academic teaching methods. His professor of drawing and painting, who had trained under Ingres, was indifferent to Seurat’s talent, and increasingly he preferred to spend time in the Academy’s and the Louvre’s library.

Eugène Delacroix’s use of vibrant prismatic colours and his pairing of complementary colours served as the foundation of the technique Seurat developed . He also studied several key works on colour theory, including Ogden Rood’s Modern Chromatics and Michel-Eugène Chevreul ‘s treatise Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colours, which contained the advice to artists to apply separate brushstrokes of pure colour to the canvas and allow the viewer’s eye to blend them optically. Rood likewise suggested that adjacent dots of different colours, when viewed from a distance, would coalesce into a new single hue.

These ideas form the basis of the radical Pontilliest technique and the move toward ¨painting with light¨that Seurat and Paul Signac developed in the 1880s.