The group of French painters rejected by the official Salon was initially referred to as intransigents. It was the playwright and critic Louis Leroy who coined the term impressionist in his derisive review of their first independent exhibition, titled The Exhibition of the Impressionists. The name was inspired by a Claude Monet painting. By the time the much-criticised artists organised their second independent exhibition in 1876, they had embraced the previously abusive epithet and proudly called themselves impressionists.

The Hague’s Kunstmuseum suggests in their fascinating exhibition ‘New Paris’ that the real starting date of impressionism should be 1867. There is no denying that it was an eventful year: Karl Marx published Das Kapital, the World’s fair was held in Paris, the Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel patented dynamite and, even more importantly, the paper clip was invented in America. That same year, sitting on a balcony at the Louvre museum, Monet painted three cityscapes that according to the art historian Linda Nochlin are “extraordinary […] plein air recordings of the contemporary city.”

The Hague’s Kunstmuseum owns Quai du Louvre, one of those ¨extraordinary¨ urban landscapes, and has managed to borrow Église Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois and Le Jardin de l’infante. The three paintings displayed side by side in The Hague establish the New Paris exhibition’s central concept. Monet installing his easel on the balcony of the Louvre is, allegedly, the moment when the proto-impressionists turned their back on painting indoors, instead focusing their attention on the outdoors. Or, to be more precise, it marks the moment contemporary painters began to observe the new buildings, parks and the rise of modern Paris, as created by Baron Haussmann. Literally out with the old, in with the new.

While Monet’s colleagues Renoir, Manet and Cézanne were still occupied with studying and copying the techniques of the old masters within the hallowed halls of the Louvre, Monet moved his studio outdoors on to the balcony. To underline the importance of this artistic shift, both Monet’s original letter requesting a balcony seat and the museum director’s permission, are on display in The Hague.

Monet, Sisley, Bazille and a few other artists started talking about arranging an independent exhibition in 1867. Luckily nothing came of those discussions, because had they succeeded there wouldn’t have been any impressionists. After all, Leroy’s mocking review of the ‘Société anonyme des artistes peintres, sculpteurs et graveurs’ exhibition in 1874 singled out Monet’s painting Impression, Soleil Levant (1874). The Monet painting’s title is what begot the movement’s name.

Paris was a filthy, smelly ol’ town consisting of a labyrinth of narrow streets lined with unloved medieval buildings when in 1852 the urban planner Baron Haussmann was commissioned by Emperor Napoleon III to modernise the city. Haussmann set about creating boulevards and avenues that cut straight through the chaotic ancient city. Train terminals and economic efficiency (rapid travel routes) were central to the plans. Haussmann, who called himself ‘artiste démolisseur’, was responsible for the demolition of 20,000 buildings, while at the same time constructing 300,000 new homes and planting 80,000 trees. Hundreds of kilometres of sewers were built, the water supply was modernised and fanciful pissoirs popped up here and there. Wider pavements and streetlights were installed, making the city much safer. Large parks, modeled on English designs, were created in the Bois de Boulogne and Vincennes. These were important public places where women, who previously were often mostly confined to their homes, could safely socialise during the day.

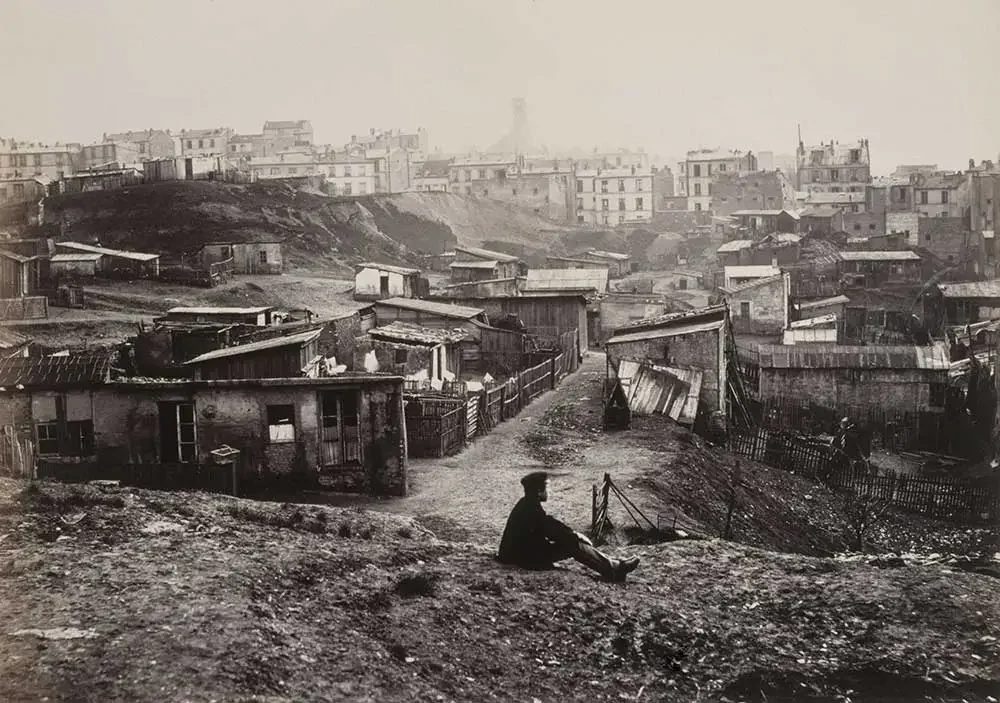

The Kunstmuseum’s exhibition features some of Hausmann’s plans, but Charles Marville’s (1813−1879) photographs of Paris are particularly revealing and worthwhile. He was commissioned by the city of Paris to capture the overcrowded, winding streetscapes with their dilapidated architecture, before whole neighbourhoods were demolished to make way for Haussmann’s shiny façades, grand buildings and wide avenues. Marville’s pictures were initially primarily intended as a visual reference for the the city’s planning office. The photos provided both a record of historic Paris and Haussmann’s radical transformation of the urban landscape. Marville’s work was so sharp and revealing that three prints were ordered of every picture and eventually they were also put on public display and published in books.

The three earlier mentioned cityscapes by Monet give an insight into some of Haussmann’s improvements. In the painting with the medieval Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois church there is a park where many people are socialising (perhaps after a church service) in the shade of the flowering chestnut trees. All the old buildings around the church had been demolished a decade earlier to create this airy and leafy public space. The same is true for Monet’s Quai de Louvre (featured as the opening image) which shows the recently widened road along the Seine attracting many Parisians enjoying a Sunday stroll on a sunny afternoon.

But it is wrong to think of Monet as a pioneer when it comes to documenting the radical changes that are occurring in Paris in Paris between 1850-1870. He certainly wasn’t the first artist to move the studio outdoors, en plein air. The Dutch painter Johan Barthold Jongkind (1819-1891) exerted an enormous influence on the young Monet and encouraged him to move his easel outdoors. Jongkind already walked around Paris in the 1850s observing the old city, recording black smoke emanating from factory chimneys against an almost clear sky. One of Jongkind’s most famous paintings is The deconstruction of the Rue des Francs-Bourgeois- Saint-Marcel (1868) in which a man on top of a building wields a sledgehammer, while on the street level there is evidence of rubble absolutely everywhere. The building in the painting is easily recognisable because of the advertisement on the wall. It so happens that it was also photographed by Marville, but in his picture none of the buildings have yet been flattened.

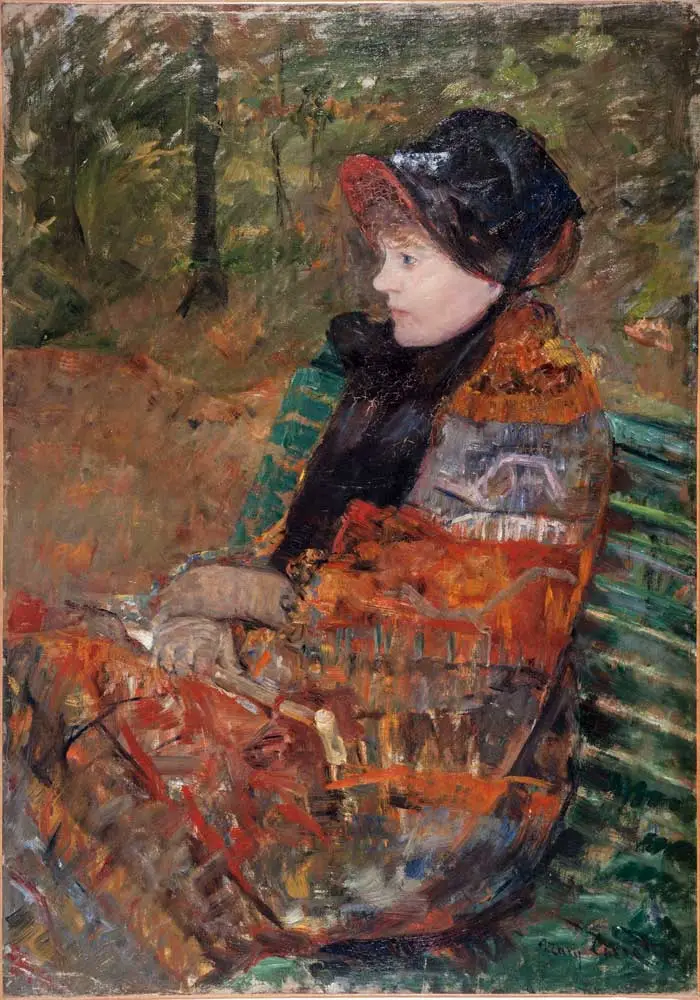

Kunstmuseum’s New Paris exhibition doesn’t just show the changing cityscape. According to the catalogue the essence of the metropolis Paris and its modernity is embodied by the Parisisienne, who stands for independence, beauty and everything that represents good taste. Paris becomes associated with fashion. It almost goes without saying that this is the section featuring works by Renoir and Manet, depicting elegantly posing ladies dressed in their coolest white dresses. The standout feature here is the exquisite portrait of Madame Darras (1868) wearing a black equestrian outfit. Edgar Degas’ teenaged ballerinas also get a look in. You can’t do an impressionist show without them. Of particular interest is the room devoted to the leading female impressionists, Berthe Morisot and the American painter Mary Cassatt. Morisot’s pastel of a wide-eyed English lady is just a simple sketch, but it is very evocative. Cassatt’s colourful Susan seated in the garden (1882-83) and the particularly impressive portrait of the artist’s sister Lydia Cassatt, day dreaming on a bench with a book in her lap. She is rugged up against the Autumn chill, dressed in a multicoloured, coat that oozes orangy warmth.

The New Paris exhibition doesn’t just show the changing cityscape. According to the catalogue the essence and the embodiment of the new and modern metropolis is the Parisisienne. She stands for independence, beauty and everything that represents good taste. Paris becomes associated with fashion. It almost goes without saying that this section features works by Renoir and Manet, depicting elegantly posing ladies dressed in their coolest white dresses. Edgar Degas’ teenaged ballerinas also get a look in. But the highlight is Manet’s exquisite portrait of Madame Darras wearing an all-black equestrian outfit. Of particular interest in this context are the two leading female impressionists; Berthe Morisot and the American painter Mary Cassatt. Morisots pastel of a wide-eyed English lady is no more than a sketch, but wonderfully evocative. Cassatt’s portrait of her sister Lydia, seated rugged up on a bench with a book in her lap, is particularly impressive when you know a little bit about the backstory. Her black bonnet emphasises her pale face and apprehensive look. Her multi-coloured coat (or blanket?) oozes warmth, while harmonising with the autumnal orange foliage.

The significant impact that the Franco-German war (1870-1871) had on the artistic community and the future impressionists is sometimes completely ignored in books and exhibitions. But this exhibition picks up on the far-reaching consequences of the war.

The Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck provoked the war, but Napoleon III, blinded by nationalistic pride, foolishly took his bait and declared war. The united German army was superior in every regard to the inadequately trained and equipped French units. Within two months of the start of the war the Germans had laid siege to Paris.

While Cézanne and Sisley fled the capital, Renoir and Caillebotte were called up, but did not see any military action. Monet took the boat for England and for a couple of months lived in Holland, probably to avoid being drafted. Jean Frédéric Bazille, who was both a benefactor and very talented colleague of the impressionists, enlisted and joined a notoriously tough regiment. He was killed in action after leading an assault on a German position. Bazille’s painting Studio in Rue de la Condamine, (1870) in which a number of impressionists are recognisable, is included in the exhibition.

After France’s defeat and the collapse of Napoleon III’s second Empire the revolutionary Paris Commune seized power in the capital. The radical government was only in power for two months before the Communards were crushed by the French army during ‘Bloody Week’, which led to tens of thousands of soldiers and revolutionaries executed or killed in action. Some of the old buildings (Tuileries Palace and City Hall) that had survived Haussmann’s demolition were set on fire, while many newly built boulevards were barricaded and became battlegrounds. The artists eventually returned to the badly damaged city, but their paintings in the following years very rarely betray the savage battles, executions and destruction that had left deep scars among many Parisians.

It’s a bit of an understatement to suggest that the first exhibition of the impressionists took place in a politically charged climate. France was in recovery mode, not in need of any radical movements or revolutionary artists. Considering that the country had quite recently experienced a humiliating war and an extremely bloody revolt, it shouldn’t be surprising that the first independent ‘Première exposition 1874’, organised by the intransigents, who had been rejected by the official Salon, caused such a shock and strong criticism.

Impressionism didn’t have a political agenda, the members came from very diverse backgrounds, and among its members the opinions about social matters differed hugely. It seems the artists were mostly interested in painting sunny pictures, showing pretty landscape, delightful women, happy families and lovely gardens. In the end no style represented the new Paris – with its clean buildings and wide avenues, rapid steam trains, reborn bourgeoisie, taste for high fashion and partying (the can-can was also introduced in 1867!) – more advantageously than ‘intransigent’ impressionism. ALBERT EHRNROOTH

New Paris: from Monet to Morisot until June 9, 2025 Kunstmuseum The Hague, The Netherlands

Nieuw Parijs: van Monet tot Morisot t/m 9 juni, 2025 Kunstmuseum, Den Haag