Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy, about 1620-25

Oil on canvas

© Photo: Dominique Provost Art Photography – Bruges

Artemisia, National Gallery in London 3 October 2020 – 24 January 2021

Don’t try this at home. Just try to imagine what it would be like to slice somebody’s head off with a sword. First of all,you have to make sure that your weapon is a sharp as a Japanese (katana) sword. If that’s not the case, as in the painting below, just use brute force. A lot of strength is required. It is messy affair and blood will splatter.

The National Gallery shows two versions of Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith beheading Holofernes and it looks like she had a fair idea of what it takes to decapitate somebody. She may have seen Caravaggio’s painting on the same theme and thought: I can do better. In her treatment of the popular subject Artemisia certainly outshone the master whom her father Orazio admired so much. While Caravaggio’s pretty Judith seems to be slicing a piece of cake, Artemisia’s Jewish widow shows absolute determination and muscle while cutting into Holofernes’s carotid aorta. Unlike Caravaggio’s painting Artemisia physically involves the maidservant Abra, who is made to restrain the Assyrian warrior in his death throes. Watch the blood spurting onto Judith’s shiny, golden brocade gown. A couple of drops have already hit the top of her cleavage. And look at that elegant bracelet which may have helped Judith to get invited into general Holofernes’s tent.

Judith beheading Holofernes, (1613-14), Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence © Gabinetto fotografico delle Gallerie degli Uffizi

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593 -1654) couldn’t get enough of the this apocryphal story (or was it her clients?) and there are two more paintings of Judith and her maidservant, after they have done the deed. In both these pictures the sense of drama is equal to anything Shakespeare or Caravaggio could have come up with. The two accomplices are about to make their getaway, they’ve ‘bagged’ the head of Holofernes, but they can hear some noise outside the tent. Judith has her sword at the ready, Abra is hurriedly concealing the blood-dripping head. The flickering candle throws a dark shadow over Judith’s face which is lit up in the shape of a crescent moon. Could it be that Artemisia intended a reference to mythology? The half moon is the attribute of the Greek goddess Selene. Artemis is another lunar goddess (as well as the goddess of wild nature), and Artemisia the painter was perhaps named after her. In the ancient Greek district Attica they honoured a bull goddess, Artemis Tauropolos, who during a ritual would receive blood drawn by sword from a man’s neck! Would the painter Artemisia have been familiar with this tale or am I reading too much into this magnificent work?

Artemis seems to have been particularly fond of empowered heroines. Her interpretation of the Jael and Sisera story from the Book of Judges in the Hebrew Bible is fairly dramatic. The cruel Canaanite leader Sisera, who has been defeated by the Israelites, is offered food and refuge in the tent of Jael. The heroine had sex with Sisera, seven times in all, according to the Talmud. This was just to tire him out, so she was forgiven. While the potent warrior had a little rest Jael drove a tent peg through his temple. This story has inspired quite a few painters and writers, including Agatha Christie (not sure if she includes the sex). Do I detect a slight smirk on Jael’s face while she lifts the hammer for that almighty blow?

Jael and Sisera, dated 1620 © Szépmüvészeti Múzeum / Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

Artemisia had a good reason to occasionally let off some steam by painting pretty horrific killings.

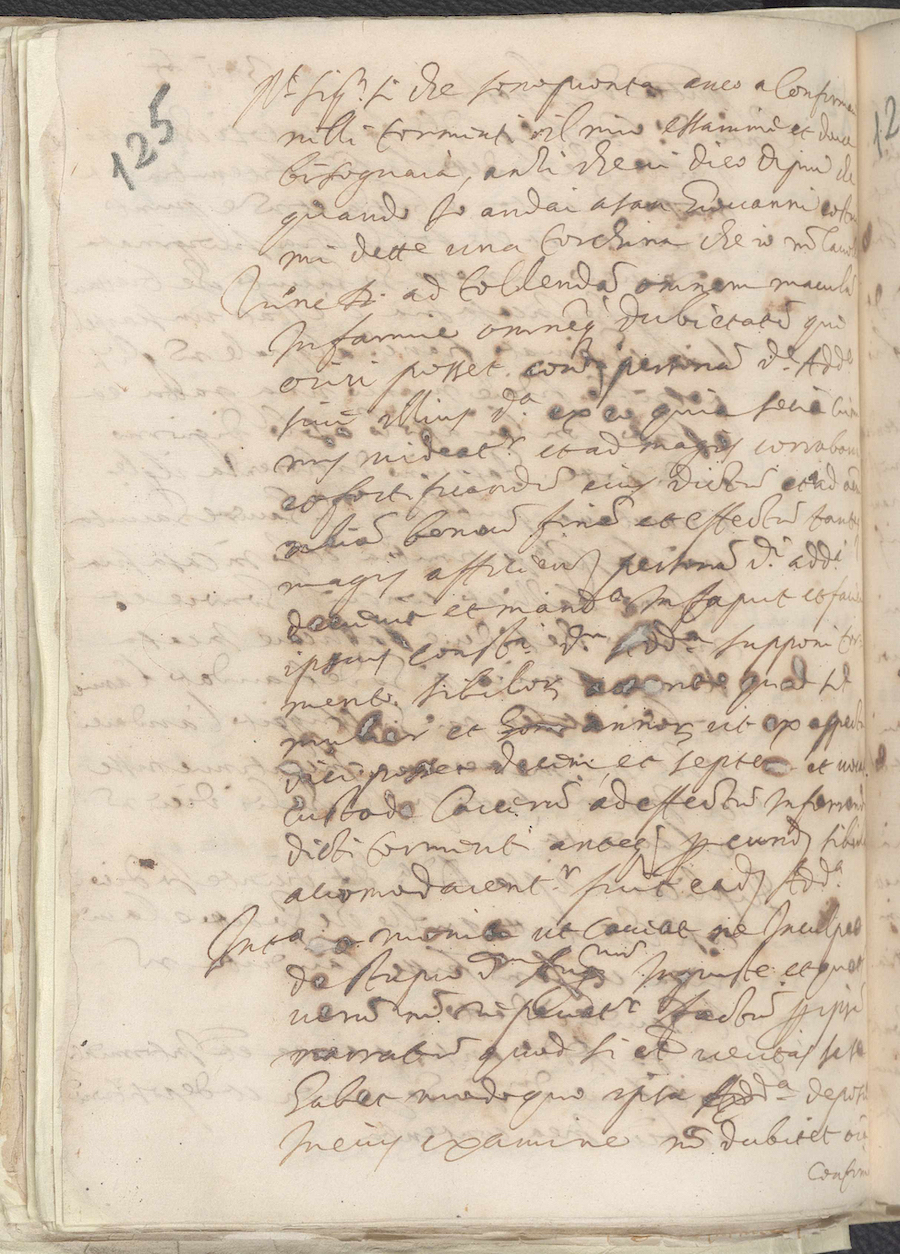

Artemisia was born in Rome in 1693, the only daughter of the Mannerist painter Orazio Gentileschi. He was heavily influenced by Caravaggio (and so was Artemisia) but after the ‘enfant terrible’s’ death Orazio rediscovered the Tuscan lyricism and a lighter palette that had marked his early career. By the time she was 15 Artemisia was probably training in her father’s studio. Her earliest signed work is from 1610. She was only 17 years old, but her Susannah and the Elders is technically already pretty stunning. The way the attractive wife of Joachim turns away and refuses the two lecherous men’s advances is very convincing. Artemisia would return to this subject several times and three depictions of the virtuous heroine are included in the National Gallery show. She was still only 17 when she was raped at home by the painter Agostino Tassi who was working together with her father. She fought back but he deflowered her and then promised to marry her. Their relationship continued for a few month after that, but when Tassi didn’t keep his promise things went awry. It was Orazio who insisted on pressing charges. The rape trial lasted for nearly nine months and it has been the subject of at least one (crappy) film and a pretty good play. In London you’ll have an opportunity to see the original account of the trial, which has never been exhibited before in public!

Artemisia was tortured to test if she was telling the truth, but at least she won the trial. Tassi was sentenced to go into exile (he just had to leave Rome), but he returned quite soon without anyone objecting (it seems). Within a day of the court case ending Artemisia married a fellow painter and they left for Florence. She set up a studio in her father-in-law’s house, and had five children in seven years – three died in infancy. Her husband turned out to be a good for nothing, but Artemisia became friends with Galileo Galilei and the poet Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger. She was the first woman to become a member of the prestigious Accademia delle Arte del Disegno and she worked for the Medicis. Her Florentine period is particularly interesting for all the self portraits. She portrays herself as various martyrs (St. Catherine of Alexandria in particular) and using her own mirror image as a model would have saved her quite a lot of money (Rembrandt also regularly painted his own likeness while dressed up in various guises). Artemisia’s patrons clearly must have admired her likeness.

Around 1618 Artemisia started an affair with the wealthy nobleman Francesco Maringhi. Nine years ago 36 letters were discovered that she wrote to her lover. Four of them are on display here. I particularly like the one in which she tells Maringhi that she no longer sleeps with her husband and then she implores her beau not to masturbate over her self portrait.

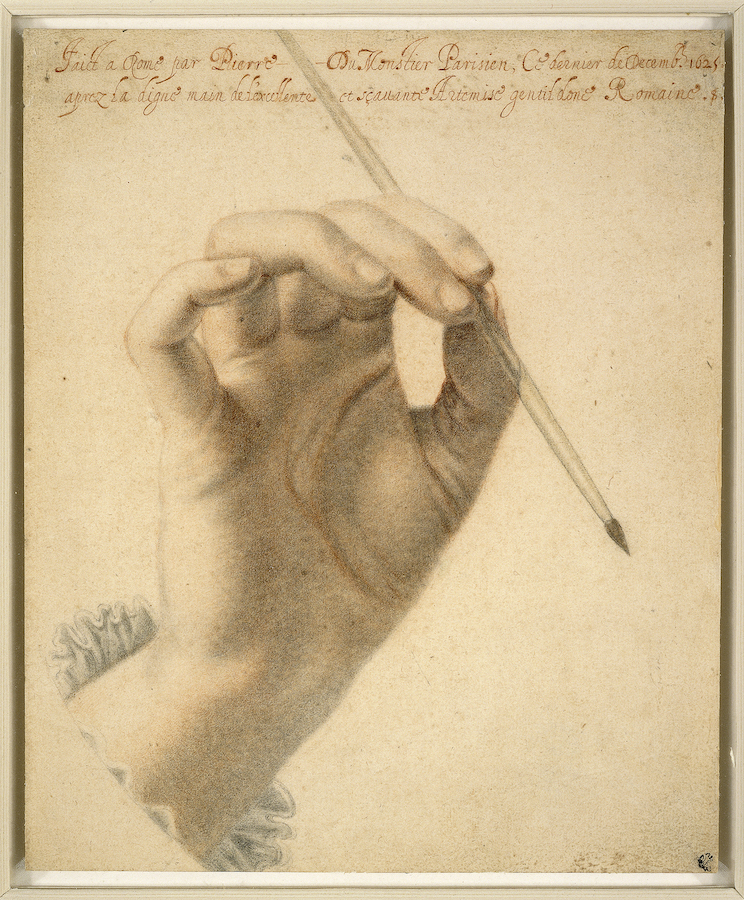

In 1620 the family moved to Rome, because Artemisia’s husband’s lifestyle had bankrupted the business. Luckily her work was now much in demand and she was the main breadwinner. Her husband describes in a letter how cardinals and princes frequent their house and studio. It is in 1620s that she produces some of her most powerful work ( which I have discussed above). She was becoming famous, even celebrated, and Simon Vouet painted a portrait of Artemisia posing with a palette and a drawing implement. She is also the subject of a portrait medal and engravings. There is even a depiction of her right hand delicately holding a paintbrush.

Much has been made of the fact that Artemisia was a woman artist. Female painters actually weren’t that unusual during the baroque era. Sofonisba Anguissola was perhaps the foremost female artist of the Renaissance. Simon Vouet (see above) was married to the Italian painter Virginia da Vezzo. And I believe that the Dutch Golden Age painter Judith Leyster doesn’t get enough credit. There were others, but perhaps I should devote a separate blog to these other fabulous woman artists.

Gender not taken into account, Artemisia deserves to be treated as one of the great painters of the 17th century because of her portrayal of women from a female perspective. Her nudes appear more realistic to me than Titian, Rubens and Rembrandt’s unclothed beauties. The way she depicts Judith’s and Jael’s emotions during the act of murder can’t be found in any other paintings from that era. And look at Susannah’s almost tearful face in the picture below. This is a voluptuous and attractive woman (compare with the rather plump woman in Rembrandt’s version), who is pestered for sex by two very ugly men. But she also gives out a sense of vulnerability that most male artists couldn’t capture.

Susannah and the Elders, 1622, A. Gentileschi © The Burghley House Collection

In the 1630s we find Artemisia in Naples where we know that she made some pictures for the well-known patron of the arts Cassiano dal Pozzo. The Infanta Maria of Spain, the Spanish king’s sister, also commissioned some works. But most of the altarpieces and other paintings based on biblical stories created in Naples fail to really impress me. Technically they are still quite brilliant, but maybe there are too many figures and the focal point becomes ill defined. Artemisia was definitely at her best when she didn’t have to focus on more than three characters. Still, among these late works there is another very evocative painting of the semi-naked Queen Cleopatra, as white as a sheet, on her deathbed.

In 1638 she went to London to assist her father who she hadn’t seen for 20 years. Orazio was working on the ceiling canvases for the Great Hall of the Queen’s House in Greenwich. Many figures are more reminiscent of Artemisia’s powerful style than Orazio’s more artificial depictions, claims the curator of Marlborough House. That is where these paintings hang nowadays, but the mansion in St. James, London, is not open to the public. But you can see the ceiling in detail by following this link:

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/an-allegory-of-peace-and-the-arts/XgKSWkEDR113Lg

Artemisia stayed in London for another year after her father’s death in February 1639. She continued to work for the Queen but how many paintings she produced is not known. The one work that is associated with this period is the famous La Pittura, Self Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (see below). I don’t believe for a minute that it is a self portrait – the subject is far too young (Artemisia would have been around 46 years old). My guess is that the allegory portrays her daughter Prudenzia who also was a painter.

This is a faithful rendition, almost to the letter, of how an allegory of painting was supposed to be portrayed. But the angle is unique and innovative. Self Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (La Pittura), about 1638-9 © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Artemisia returned to Naples in 1640 and continued painting, but by 1649 she is again bankrupt. Her last dated picture is from 1652 and it is another Susannah and the Elders which also features in the exhibition.

Artemisia Gentileschi, the first truly great woman artist, is still recorded as being alive in August 1654 when she paid her taxes. The excellent catalogue accompanying the exhibition suggests that she died soon after that. I sincerely hope the tax bill wasn’t a killer.