The Victoria and Albert is now the unofficial rock and pop museum of Great Britain. After successful shows devoted to Kylie Minogue, David Bowie and very recently the revolutionary late 60s pop scene, the V & A now tries to get under the skin of one of the most significant bands of the last century.

While visiting The Pink Floyd experience at the Victoria & Albert Museum I gradually started feeling like I was walking with dinosaurs. Very early on I am reminded of the fact that everything Pink Floyd represented in the 60s and 70s has now vanished. Well, at least from the pop charts.

We follow in the footsteps of these giants from conception, early flight (with bizarre bright feathers), then the spaced out era followed by the transitory phase when they come back to earth while still pondering what is up there in the space between our ears. But the growth spurt between Dark Side of the Moon and The Wall was too fast and the band’s tours became operations of Titanosaur proportions. Playing to massive audiences proved to be depressing and they were mired by constant high expectations from the critics and fans. After Roger Waters left I feel that the very exciting and colourful dinosaur that Pink Floyd once had been, slowly but surely started to ossify. Their Mortal Remains, which is the name of the exhibition, is a worthy, at times very exciting, but slightly ponderous monument to Pink Floyd’s innovative achievement in rock music.

At the entrance we are given an audio guide that comes alive with music and talk every time you move into a new space or in front of another screen with interviews and concert clips. You enter the exhibition through a sort of recreation of their first touring van. The original Bedford van was not much bigger than today’s people carriers. They could fit all their equipment in there. By the time of The Wall tour they needed 30 mega trucks to move around. We are reminded that the embryonic Pink Floyd were a R & B band playing psychedelic versions of standards like ‘Roadrunner’ and ‘Louie, Louie’. They could have become an eccentric cover band if it wasn’t for the brilliant, multi-talented Syd Barrett.

In the UK Pink Floyd were pioneers with ‘sound in the round’, psychedelic slide projections and what were already called multi media effects. Initially their extended jams like Interstellar Overdrive and Astronomy Domine mainly seemed to appeal to acid heads and underground types. Fueled by LSD and his art school background Syd created ‘music in colour’. He played guitar, sang and composed and had, curiously enough, also an ear for writing commercially appealing songs. The singles Arnold Layne and See Emily Play were weird and wonderful little vignettes. The former made it to number 6 in the British chart. Syd penned most of the songs on the debut album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967). From the little evidence and the interviews offered in the exhibition it is made clear that Barrett was going crackers because of his drug abuse. A girlfriend says in an interview that he was “very unusual, the real package”. Drummer Nick Mason declares that “you couldn’t overemphasize his importance” and Roger Waters is not just being kind when he says that “Pink Floyd wouldn’t have existed without Syd”.

When Syd became incapable of producing much more than one repetitive note on his guitar and he often didn’t turn up at gigs, his schoolfriend David Gilmour took over guitar and later also vocal duties. Barrett was finally pushed out in 1968. Waters and Richard Wright struggled for a couple of albums after that with finding their own composing style and some of the songs from the transitional period leading up to Dark Side have not aged very well. They contributed to a few film soundtracks and showed very little interest in producing chart topping material. But by the time the long player Meddle ( 1971) was released the band sounded like a tight and well-oiled unit with writing contributions from all four members. Several tracks from that album and the forthcoming Dark Side project were turned into a ballet by the famous French choreographer Roland Petit. Originally PF performed the tracks live, positioned behind the dancers. You can see the choreography for Echoes here.

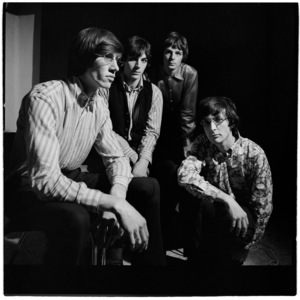

In the exhibition the first phase (1965-1972) is displayed in overly darkened rooms, perhaps emulating the underground venues (the UFO Club?) that PF used to play in the early days. We are offered letters, scribbled lyric sheets, black & white photographs, instruments, posters and various items of clothing all locked up behind glass. It is the usual, not terribly exciting stuff and mainly of interest only to the real fans, I would think.

Several documentaries have been made and books have been written about how Dark Side of the Moon (DSM) came about. The album was a scene changer for the band and set new standards for the then popular concept album. It was the first PF album that was commercially successful in America and it has remained hugely popular. That is an understatement, if ever. DSM continues to hold the record for the most charted weeks on the Billboard 200. This is also where the exhibition starts to get more inspirational. Could it be that the curators only really begin to like the Floyd at this stage?

We get an insight into how Storm Thorgerson’s famous prism-pyramid cover design came about which is also a reminder of what why albums in the vinyl age had much more to offer than today’s digital downloads. The enormous desk on which DSM was mixed can be seen in the entrance hall of the V & A.

The room with Pink Floyd’s instruments and technological arsenal also includes a few min mixing boards that can be used by the public. You have an opportunity to listen to individual channels of the track, Money. Despite having heard the song hundreds of times ( it features on every other business programme on TV) it is rather refreshing to hear the guitar, the vocal, the saxophone and the ‘bitty’ keyboard parts on their own.

We get a behind the scenes look at the recording process of Wish You Were Here. The album contains (just like The Wall) a number of references to Syd Barrett and his decline into madness and isolation. None of the band members had been in contact with him for years. But one day during a mixing session of Wish You Were Here, Barrett suddenly turned up at Abbey Road studios. He was overweight, with his eyebrows and head shaven and everybody struggled to recognise him. He made a “desultory” and absent impression. A small polaroid photograph of Syd in the studio that day in June 1975 can be seen in the exhibition. It was the last any member of the band heard from Syd, until his death in 2006.

The next exhibition space is the most imaginative, thanks to some very famous inflatables and stage sets. With Animals Roger Waters together with the designers from Hipgnosis introduced a surreal architecture on a scale that hadn’t been seen before on a rock stage. In a way it is surprising that stage architecture is only introduced at this point, considering that three of the members (Waters, Mason and Wright) had studied architecture at the Regent Street Polytechnic in London. The Animals sleeve (with the cathedral-like Battersea Power Station) is so iconic that it was referenced in Danny Boyle’s Olympic Games opening ceremony.

The tale of how the giant inflatable pig (apparently named Algie), that was constructed by the Zeppelin factory, escaped during a shoot for the album cover, is very amusing but could have ended in an airplane disaster. Roger Waters was definitely the dominant force in the band by the time the double album The Wall (1979) was released. The tensions were also running high, not only between Waters and Wright but also between the band and producer Bob Ezrin. All this is not really explored in any depth in the exhibition. A white brick Wall has been created in the exhibition but it is not the original one.

With the exception of one song, The Final Cut (1983), was written by Roger Waters. It reached the top of the British album chart, perhaps helped by its anti-war and anti-Thatcher message. After this solid but mostly quite unmemorable project Waters left the band, perhaps not expecting that Gilmour would continue. But in the post-Waters era the album covers became more intriguing than the content of the songs. Thorgerson remembers with a rather wry smile how the A Momentary Lapse of Reason cover was created (featuring 700 hospital beds on a beach) and the fantastic costs that went into setting up this shoot.

The two sculpted metal heads , forming a third face, that can be seen standing in a field on the cover of The Division Bell (1994) have been given a room of their own. But then they are as high as a double-decker bus. Yes, by this stage the art is better than the music but luckily the exhibition finishes on a musical high note.

In the last exhibition space we are offered an immersive evocation of the last performance that the original four piece gave at Live 8 in July 2005. It really comes as close to the real thing that you will ever experience, because Pink Floyd have with The Endless River, a tribute to Richard Wright, who died in 2008, taken a final bow.

If you are a fan you need to see this show. If you’re not, you are in danger of turning into one after hearing the audio guide to this exhibition.

Their Mortal Remains at the V & A, London until 1 October 2017.

46 thoughts on “WISH YOU WERE AT THE PINK & FLOYD MUSEUM”

Comments are closed.