Georgia O’Keeffe retrospective at Tate Modern (until 30 October 2016)

Georgia O’Keeffe’s painting Jimson Weed/White Flower No.1 is still the most expensive work of art by a woman artist sold at auction. It fetched $44.4 million at Sotheby’s in 2014 and it shouldn’t surprise anyone that Tate Modern treats it as a crowd puller. That is perfectly fine with me, but the Weed painting is actually not one of the highlights of the show, as far as I am concerned. There are many works in this important exhibition that are superior in all sorts of ways.

The Tate Modern’s retrospective is the largest ever devoted to Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) outside of the USA and it is revelatory, not in the least because it doesn’t dwell too much on those damned blossoms.

I love flowers. I have a garden full of them.

I visited the press viewing of this exhibition in the morning and in the afternoon I went to the opening of the Hampton Court Flower Show (see review below). That is a lot of floral ado in a day and it proves my point that I adore flowers.

OK, O’Keeffe is particularly well known for her extreme close-up flower paintings that tend to be interpreted as some kind of celebration of female orifices. O’Keeffe was adamant that the erotic symbolism was unintentional and she would get extremely annoyed with critics who went on about it. Here is a quote from her brochure ‘About Myself’ (from 1939): “ Well- I made you take time to look at what I saw and when you took time to really notice my flower, you hung all your own associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see of the flower – and I don’t.”

O’Keeffe was equally irritated by people trying to label her as a ‘woman artist’. So, I am striving to avoid gender issues in this review.

Some of O’Keeffe’s early, surprisingly experimental, abstract charcoal drawings were first exhibited a century ago at the ‘291’ gallery in New York, without her knowledge. The gallery owner was Alfred Stieglitz who barely knew her then but later became her husband. Today Stieglitz is mainly known as a photographer and a number of his pictures feature in the current exhibition. Georgia can be seen in hundreds of his snaps. She could look uncompromisingly severe, even spartan wearing black attire, male shoes and with her hair pulled back tightly. But this image may have been one of Stieglitz’s creations and he was definitely responsible for making her expose her softer, dreamy, very feminine side. Georgia also seemed perfectly willing to pose naked for Stieglitz.

Georgia O’Keeffe grew up on a farm in Wisconsin, the second of seven children. This state calls itself ‘America’s Dairyland’ and borders Lake Michigan, but it is very different from New Mexico, where she spent most of her mature life. After studying art in Chicago and New York she also lived in Texas. But in 1918 she was back in New York, mainly focusing on oil painting. She was fascinated by synaesthesia and the idea that “ music could be translated into something for the eye”. Many of her early works are inspired by sounds or music, and this encourages her to experiment with abstract composition.

Stieglitz and O’Keeffe were already an item in 1919, despite the fact that Alfred was still married. She had become his muse, but Stieglitz’s influence on her early works (particularly his cloud photography) becomes obvious in this exhibition. In the mid-1920s O’Keeffe starts to paint cityscapes of New York. She lived with Alfred on the 30th floor of a skyscraper and for a while got a kick from the roaring dynamic of the big city. Her best picture (see below) from this period is observed from street level depicting nocturnal New York, perhaps unconsciously, resembling a giant canyon lit by streetlamp halos and a blue moon.

In the 1920s she also spent much time at the Stieglitz family’s summer house on Lake George in upstate New York. From my own experience, I know that this is a magical place and although she felt ”smothered with green” some of her most pleasing works were created there. The motifs include clouds, red apples, autumn leaves, a simple farmhouse door with window and a painting of the actual lake as peaceful as you will never see it today. The most captivating painting from that period exhibited here is From the lake no.1 which in a non-figurative manner suggests the crash and swirl of a colourful tempest over the water.

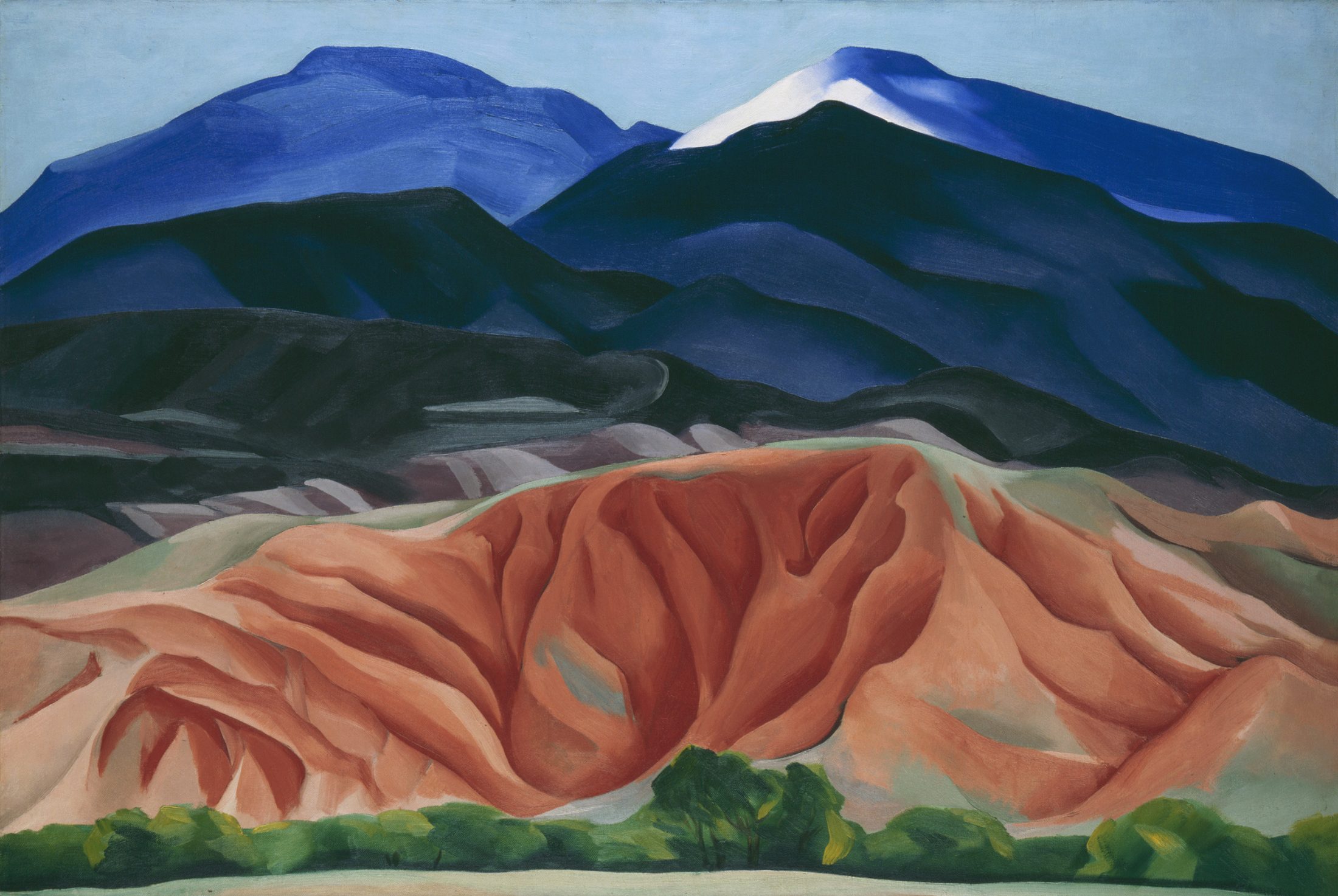

By the early 1930s, Stieglitz had become openly unfaithful and also too controlling of O’Keeffe’s work and, as a consequence she suffered a nervous breakdown. She needed to get away from him, for at least half of the year. Georgia had already discovered that New Mexico’s arid high altitude desert country “fitted to me exactly”. In Taos and Alcalde, she also made new friends and contacts and all of this resulted in a whole new range of motifs being introduced into her work. The wooden crosses on the mountains, the ancient mud brick architecture, the flat and wide tablelands, it all fascinated her. The pared-down landscape of New Mexico and the lack of too many social distractions produced a stripped down style that is uncompromising but still seems to suit the occasion and the motif. The Badlands are celebrated in vivid (earth) colours (green, intense pink and red scoria, purple, lavender, etc.) and fill the canvas to the point of almost obliterating the sky. Contrast this with the sparse palette O’Keeffe uses to capture the architecture of the native Indians. But human beings are strangely absent in her work.

Then there were the bones she found in the desert. It is tempting to associate the skull paintings with death but she denied that rather obvious interpretation. She just “enjoyed” the irregular shapes. She found them very lively and it didn’t occur to her that skulls and bones could be associated with death, or so she claimed.

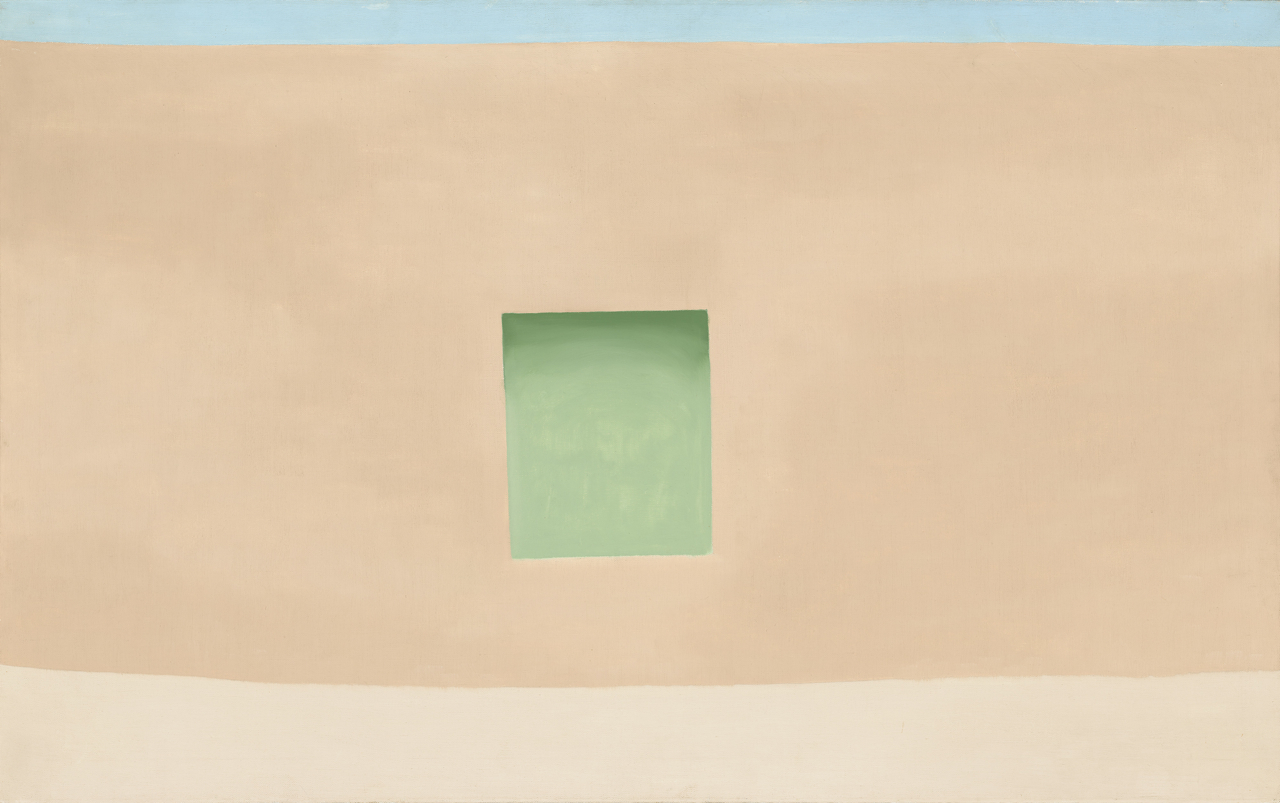

I detect more death symbolism in the so-called ‘patio paintings’. in these she concentrate solely on a long patio wall made out of mud brick with only a door and a thin slice of blue sky for variety. This green door at her house in Abiquiú (see below) is depicted either closed or it appears to be open, revealing a dark, mysterious space. She became obsessed with this motif after Stieglitz’s death in 1946. In these series Georgia tries to catch the variations of light and in the process she records something like the shifting shadow of death. There is a sense of closure in the large canvas My Last Door (1952-54). The palette has been scaled back to white, grey and black and it all becomes so non-objective that I am reminded of Malevich’s famous Black Square painting from 1915.

With the seriality, the abstraction returns to O’Keeffe’s work, but she won’t let go of the figurative inspiration.

O’Keeffe made her adobe dwelling in Abiquiú, with its stark and empty interior design, her permanent home in 1949. In the 1950s she devoted much of her work, again to the point of abstraction, to a few very remote landscapes in the grey hills that she thought looked like “a mile of elephants”. She would hike and camp there while working on her series of oils depicting the Black Place and the White Place.

In the late 40s, Georgia O’Keeffe was already a fairly prominent artist and major art institutions devoted solo exhibitions to her work, which meant that she got to travel more by aeroplane. While looking out of the window during those flights, she started to become fascinated with the formations of clouds. She noticed during one such flight that “ the sky below was a most beautiful solid white. It looked so secure that I thought I could walk right out on it to the horizon if the door opened.”

That sense of being able to walk on the clouds like stepping stones is exactly what she depicts with an almost childlike glee in the series The Sky above the Clouds. It is in these works she achieves what she herself described as “some marvellous patterns of maybe ‘Abstract Paintings”.

By the early 1970s, O’Keeffe’s degenerative eye condition had made it impossible for her to work without an assistant. Maybe it is for that reason that the exhibition at Tate Modern doesn’t delve into the last decade of her life.

I read somewhere about O’Keeffe’s very acute business sense. By the end of her life, she made a very good living from her paintings and at the same time maintained ownership of nearly half of her total output of paintings. Her estate was very good at buying back many of her early works at auction and from private collections. At the same time, all this activity by the artist on the market also helped to stimulate the demand for her works.

It is a shame that we don’t get to see any of her very late works which were partly created with the help of her assistant and young friend Juan Hamilton.

Finally, it is hard to avoid the notion of gender. Would we look differently at Georgia O’Keeffe’s work if we didn’t know she was a woman? Very possibly, but I only detect in her floral paintings a clear indication of her gender. But that is the only time I feel I am watching a work by a female artist.

O’Keeffe was one of the first truly American painters, who created an individual style which shows very little European influence.

This revealing retrospective has been long overdue but now that it is here (in London) you simply must go and see it. It is that simple.