London’s National Gallery and The Hague’s Mauritshuis museum have put together the first exhibition in the UK devoted to Nicolaes Maes, a Dutch Golden Age painter who deserves to be more well-known.

Even in the Netherlands Nicolaes Maes (1634–1693) is not really a household name, but I reckon that he was one of the Dutch Republic’s major influencers (when it came to painting). His intimate, often humorous, domestic interiors have had a significant influence on the work of Pieter de Hooch and Johannes Vermeer.

Nicolaes Maes is considered to have been Rembrandt’s pupil. It is a fair assumption but there is no certainty. The only ‘evidence’ we have comes from Arnold Houbraken’s history of Netherlandish Art, De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen (1721). Houbraken mentions nonchalantly that Maes learnt painting from Rembrandt and drawing from an unnamed “common artist”. And yes, some of the early works in this fascinating exhibition at the National Gallery are blatant copies of the master’s work. We know that Maes left his hometown Dordrecht and moved to Amsterdam before he had turned fourteen. If he was apprenticed to Rembrandt it would have lasted for about four years.

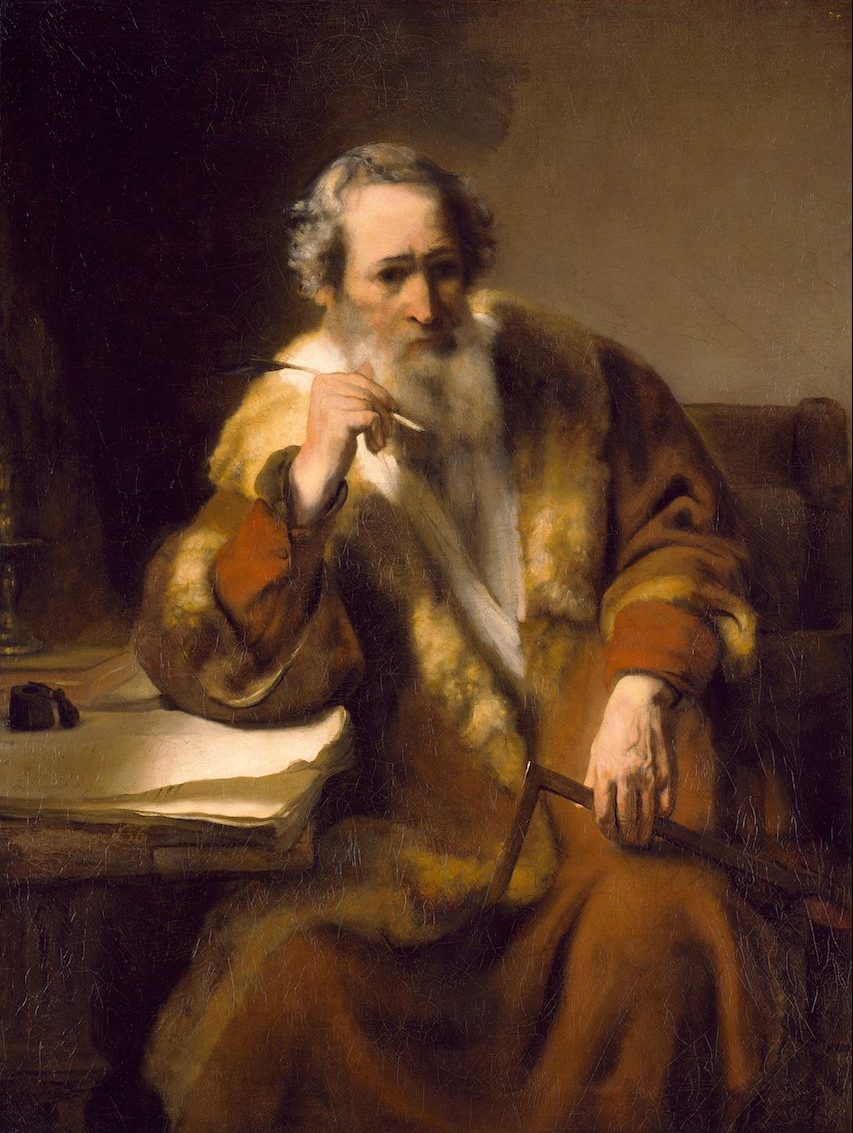

Even if he wasn’t Rembrandt’s pupil, it is obvious that he studied Rembrandt’s technique and his subject matters very carefully. Maes became so proficient that The Apostle Thomas (see picture) for 200 years was admired as a work by Rembrandt van Rijn. This depiction of an old man (as a saint) had Rembrandt’s signature and was dated 1656. In 1885 it became clear that the signature was false while the date was original. During the latest restoration in 1977 Maes’ name was not found anywhere, but all experts seem to agree that the only other artist, apart from Rembrandt, who could have painted such a warm and sympathetic portrait of the saint is the man from Dordrecht.

© Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister

Nicolaes Maes was born in Dordrecht, a city in the south of Holland that has retained some of its atttractive features from the 17th century. Dordrecht was in the early days of the Dutch Republic an important commercial and religious centre. It was also (in the 17th century) the birthplace of many talented painters. Some of the most well-known artists are Aelbert Cuyp, Samuel van Hoogstraaten and Aert de Gelder.

Not much is known about Nicolaes’ childhood, but he did settle in Amsterdam around 1646. None of the work that he produced during that period (he was in his teens) is featured in this exhibition. The competition in the 1650s in Amsterdam would have been very tough for an artist who hadn’t yet established himself. After his apprenticeship (to Rembrandt?) Maes returned to Dordrecht in 1653 and married a widow. The earliest works on display are history paintings, which was the genre that was most respected and commanded the highest fees. I think his take on Dürer’s engraving Adoration of the Shepherds is rather good. It is more or less an exact copy, but it has been enlarged and the oil paint colours add an extra dimension.

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

After moving back to Dordrecht Maes seems to have established himself pretty quickly. He took up a form of genre painting that was becoming very popular and required a lot of technical skill. The influence of Rembrandt is still discernible, but Maes starts to work with more saturated colours (warm red and deep shiny black). I think Gerrit Dou’s exacting style had a profound influence on Maes, even though there is no obvious evidence. Maes’ domestic scenes pay great attention to detail, but they also quite often have a moralistic undertone. Lacemakers (see picture) are a subject that appealed to Maes (and Gerrit Dou!). The Old Lacemaker (see picture) shows an old, but industrious woman who is a good example of the Calvinist work ethic. Maes also made several paintings depicting an old woman nodding off during work and this is meant to illustrate idleness, which protestants of course couldn’t approve of. But Maes also likes to mock his subjects and his clients particularly appreciated that side of his repertoire.

© Mauritshuis, The Hague / Photo: Margareta Svensson

The exhibition features four different Eavesdroppers (see featured image at the top of the page and below) and they are Maes’ signature paintings. The Eavesdroppers have all in common that in the foreground of the painting you see a woman standing/hiding on the landing or on the stairs spying on a maidservant and her lover in an adjoining room, basement or hallway. We can see the lovers, but the eavesdropper can’t. She looks straight at the viewer with a smile and raises a finger to her lips, thereby involving us in her secret overhearing business. There is a didactic message: servants distracted by amorous suitors are neglecting their duties. These type of pictures confirm the contemporary view that domestic servants were in general pretty deceitful. All these domestic scenes incorporate elements of meticulous still life painting (a cat, a detailed map on the wall, a beer tankard, books, etc.). Surely the ‘School of Delft’ painters (de Hooch, Vermeer) saw some of Maes’ work and found inspiration in his well observed intimate interiors.

Maes’ interest in genre scenes only lasted a few years and his decision to suddenly exclusively devote himself to portraiture painting can only have one explanation: portrait painting was financially more profitable than genre painting. Maes moved back to Amsterdam where his potential clientele was richer and perhaps even more sophisticated. He briefly revives his Rembrandtesque approach, but in the 1670s the brown hues fell out of fashion and Maes adopted the lighter French Baroque style. The portraits in this exhibition are well chosen but only a handful hold my attention. Maes was very versatile , but he was no van Dyck even if he, after a visit to Antwerpen, desperately tried to emulate the swagger and flashy style of the Flemish master. Nicolaes Maes was an accomplished portraitist, but his true talent and originality can be seen in his warm and humorous domestic scenes.

© Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London

Nicolaes Maes, Dutch Master of the Golden age at The National Gallery, London, until 20 September 2020