Helene Schjerfbeck at the Gabrielle Jungels-Winkler Galleries, Royal academy , London. On until 27 october 2019

How many Finns with an artistic bent can you mention?

I don’t blame you if you can just think of two and at a stretch three: the composer Jean Sibelius, the architect Alvar Aalto and maybe you are even familiar with the creator of the Moomin characters, Tove Jansson. I would like to add another Finn to that list: the artist Helene Schjerfbeck. The Royal Academy of Art seems to agree and has organised her first solo exhibition in Great Britain, featuring 65 works.

This century there have been a number of successful Schjerfbeck retrospectives in The Netherlands, France, Germany and Japan. In Nordic countries Schjerfbeck is celebrated and seen as Munch’s, Hammershoi’s and Zorn’s equal, but in this country she is virtually unknown, despite the fact that she spent two extended periods in Cornwall (in 1887/88 and in 1889/90).

Helene Schjerfbeck (1862-1946) lived through a transitional period in painting and she was no stranger to experimenting. But she was already in her forties when she started to find her own distinctive style. Throughout her career she portrayed herself and through these self-portraits we can see how her technique changed from naturalism to pared-down modernism. In her final years her portraits and still lifes become so stark as to appear almost abstract. The portraits she created in her youth feel more like a mirror image. But at the dawn of the 19th century we are offered a glimpse of her physical and psychological state of mind. And then in the last decades of her life Schjerfbeck presents a kind of mask, without hiding behind it. Yes, she is willing to reveal her anxieties and pain without sentimentalizing.

Schjerfbeck’s extraordinary talent was discovered early on. At eleven she was the youngest student ever to have been given a scholarship and to study at the Finnish Art Society’s drawing academy. After passing her exams she continued her studies with a private teacher and in 1880 she was awarded a travel grant by the Finnish Senate. She took herself off to Paris, which was starting to attract women artists from all over the world. Over the years she attended several academies in Paris and became good friends with a number of female colleagues. She exhibited at the Salon, became part of the emerging artist colony in Pont Aven and embraced the naturalistic French style.

My personal favourite from this early period is The Door which shows an empty grey chapel interior with a brown wooden floor and a closed black door. But it is the warm light that shines from underneath the door that turns this slightly abstracted picture into an almost spiritual experience. Who is about to come through that door? The crucifix in this same chapel inspired a self-portrait by Gauguin.

Schjerfbeck’s friends Adrian Scott Stokes and his Austrian wife Marianne invited her to come and join them in St Ives where a small colony of artists were establishing themselves in this traditional Cornish fishing community. She immediately felt very inspired by the quaint setting. One of her most loved paintings, The Convalescent ( see below, 1888). We see a bright-eyed child recovering from illness, which was quite a common subject in those days, looking at some “first greenery” (the original title). Is it a form of self-portrait? Schjerfbeck broke her hip as a child and had a limp throughout her life.

In St. Ives Helene picked up painting technique tips from Adrian Stokes. She participated in local exhibitions and also exhibited in London where at least one of her works sold for good money. The pictures from that period were well crafted but today we tend to classify them as Victorian and the fact that they more often than not feature children makes them err on the sentimental side.

In the 1890s Finnish art collections only contained a handful of masterpieces of international standard. Schjerfbeck was sent by the Finnish Art Society to St Petersburg, Vienna and Florence to make copies of works by masters like Velazquez, Giorgone and Holbein. It is clear that copying the grand masters also influenced her own work. For a number of years she took up a teaching position at the Finnish Art Society in Helsinki, but her health remained fragile and she suffered long bouts of illness.

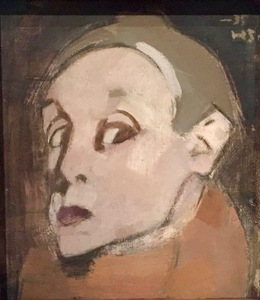

In 1902 she finally quit her job and moved in with her mother who lived about 50 km north of Helsinki. For the next 15 years she never visited the capital. She opted for a fairly isolated existence and her mother and local friends and acquaintances became her main subjects. It was in Hyvinkää that Schjerfbeck developed her own brand of modernism. The increased intimacy is combined with a pared down colour scheme. She focuses on facial expressions that increasingly reveal the deepest human emotions. But as she gets older the faces loose their individuality. Is she depicting a type? The contours are sharply drawn, with clear lines, and faces are devoid of too many details. I am reminded of Japanese kabuki masks, but the painter lets the viewer make up the story behind the mask.

Then there are the self-portraits, easily the highlights of this exhibition. Each one seems to reflect an element of her ‘tempestuous inner life’. Schjerfbeck’s social reticence didn’t stop her from keeping up to the date with the latest art trends. She studied the international art magazines that her friends sent her. But she refused to involve herself in the lively art scene that developed in Helsinki at the start of the 20th century. After the journalist-art dealer Gösta Stenman started to buy and champion her works they appeared more regularly in exhibitions. Not long after she met Stenman in 1915, the forester, author and artist Einar Reuter also came into Schjerfbeck’s life. Their friendship was (probably) never sexual but it was very important and close . Reuter encouraged and admired her work and wrote a biography that has proven to be invaluable for biographers following in his footsteps. Stenman managed to persuade her to visit an international exhibition at the Ateneum in Helsinki where she saw works by Gauguin and Cezanne. It’s obvious from her extensive correspon-dence that they fired her imagination. once more. Some of her other sources of inspiration were Daumier, van Gogh, Matisse and Othon Friesz.

valokuvaaja: Eweis, Yehia

Studying the techniques of these painters changed her own working methods. The perspective becomes flatter, she deliberately distresses the canvas by scraping, reapplying and once more scraping paint in order to achieve a dampening of colours. By doing this she can also very effectively mimic the materiality of the textiles.

Is this a defiant or surprised look? The artist is once more playing a role, a type.

With age Schjerfbeck looses interest in creating likenesses. She is still trying to portray the truth, but it is the psychological truth she is after. By the 1930s her models appear to be more concerned with their own inner thoughts and give a restrained impression. Droopy or half-closed eyelids help to create that image. By giving the portraits titles like The Obstinate Girl, Circus Girl, the Teacher and Girl from California the identity of the individual becomes irrelevant. The model (and most of them are women) is a type and has been picked for that purpose .

After her mother’s death in 1923 Helene settled in Ekenäs. a coastal town where the locals mainly spoke Swedish (Schjerfbeck’s mother tongue). Stenman (her trusted art dealer) encouraged her to return to some old subject matters and this resulted in some revealing works that added much to the original. In the 1930s Stenman also persuaded her to paint more self-portraits and some of the most powerful ones can be seen in this exhibition. It is in these late self-portraits that she opens up and stops hiding behind a mask.

While the war was raging she moved in 1944 to a comfortable hotel just outside Stockholm to get some peace and quiet. Stenman supports her financially but her contract stipulates that she must sell all her work via him. This keeps the pressure up and she never stops working. There is no time for being complacent. The last series of portraits are even more harrowing and brutally honest.

She is petrified and staring straight at the viewer or there is resignation and introspection. At times there almost seems to be an unexpected sense of humour. She has already recorded her decline before she moves to Sweden, but without any self-pity. In the last few years she emphasises her own mortality. The paint is often troweled on and then partly scraped off. Her eyes have become empty sockets, the oval head resembles a skull, but she remains defiant until the end.